Donald Kuspit : Concerning the Spiritual in Contemporary Art

One of 19 essays in the catalog of "Abstract Art : Abstract Painting 1890-1985" ..for the 1986 exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

I have indicated which of the images below were selected by me — by Kuspit from the exhibition —or by Kuspit from other sources.

**********

Kandinsky, Composition VII, 1913 (my selection)

The title of this essay recalls Kandinsky's brief book of 1910, and that’s where Kuspit begins:

As Wikipedia tells us, Kandinsky is "credited as one of the pioneers of abstraction in Western art". And as we can see in the above example, he made paintings without identifiable objects.

In his book, Kandinsky does indeed excoriate a typical salon exhibit of the art of his time - all of which represented "items of nature". But when he offers examples of those who "search for the abstract in art", he offers Rossetti, Bocklin, and Segantini, all three of whom present identifiable objects and figures. And he even tells us that:

Segantini, outwardly the most material of the three, selected the most ordinary objects (hills, stones, cattle, etc.) often painting them with the minutest realism, but he never failed to create a spiritual as well as a material value, so that really he is the most non-material of the trio.

Giovanni Segantini, the Bad Mothers, 1894 (my selection)

Kuspit, however, immediately makes "abstract art" synonymous with "non-objective art" when he next writes that:

After three-quarters of a century of abstract art and the development of an abstract art that seems to have deliberately purged the spiritual Stimmung (atmosphere) that Kandinsky expected abstraction to distill, abstraction itself has become materialistic (Frank Stellas work is a major example)

"

Stella is attributed with the following quote form the late sixties: "A painting is a flat surface with paint on it – nothing more". That may suggest he did not consider his own paintings to be spiritual. Possibly, he would have said the same about every other painting that he saw.

Frank Stella, Lac Lorange III, 1969, 108 x 162" (my selection)

But must that make his work any less spiritual for the rest of us ? I would hardly say that "Warmth of heart or slightest stirring of the soul" (two criteria for spirituality offered by Kandinsky) are missing from the piece shown above. Indeed, I find even it’s tiny internet jpg to be thrilling and uplifting - and no paint is present at all.

This raises the question "spiritual to whom?" - and so far Kuspit would rather speculate or report on someone else’s usage of the word than his own. That conforms to the parameters expected in the academic publications of our time — and Kandinsky was way way outside them. He was not shy about relying on his own spiritual authority to tell us that paintings with religious subject matter were not necessarily spiritual. And as he imagined a great pyramid of spirituality, he tells us that the closer you are to the big crowd at the bottom, the less you understand the work of those very few enlightened ones near the top. (Among whom, presumably, he counts himself)

If you dare not claim a high level for your own spirituality - how dare you write about it.

The above assertion would probably have made sense to Kandinsky, whose paintings might serve as evidence for his qualifications. It is thoroughly unacceptable, however, in the agnostic university artworld of today.

What has happened in part is that today abstract art is no longer an oppositional art, especially in critical opposition to what Mever Schapiro called the "arts of communication." For Schapiro the problem is the pressure on the artist "to create a work in which he transmits an already prepared and complete message to a relatively indifferent and impersonal receiver. In the case of most contemporary abstract art. this means that abstraction itself has become a prepared and complete message, "calculated and controlled in its elements," a predictable aesthetic experience impersonally transmitted. Abstract art is no longer understood as a mystical inner construction, transmitting inner meanings through the "quality of the whole, available only when the proper set of mind and feeling towards it" have been achieved. The abstract work of art tends to become another reproducible communication.

The Schapiro quotes appearing above came from his 1957 essay "The Liberating Quality of Avant-Garde Art", Meyer Schapiro tells us that :

Another aspect of modern painting and sculpture which is opposed to our actual world and yet is related to it- and appeals particularly because of this relationship-is the difference between painting and sculpture on the one hand and what are called the "arts of communication." This term has become for many artists one of the most unpleasant in our language. ……… The artist does not wish to create a work in which he transmits an already prepared and complete message to a relatively indifferent and impersonal receiver. The painter aims rather at such a quality of the whole that, unless you achieve the proper set of mind and feeling towards it, you will not experience anything of it at all.

So it is Kuspit, not Schapiro, who asserts that "it is abstraction itself that has become a prepared and complete message".

Schapiro had written an encomium for avant garde art, while Kuspit presents a sharp critique of non-objective painting: it’s become materialistic, calculated, and controlled. To back it up, he mistakenly credits that critique to Schapiro - and that thirty year interval that followed Schapiro’s essay was crucial: Modernism had been eclipsed by post-modernism. It had become old hat - and as Schapiro wrote:

In discussing the place of painting and sculpture in the culture of our time, I shall refer only to those kinds which, whether abstract or not, have a fresh inventive character, that art which is called "modern" not simply because it is of our century, but because it is the work of artists who take seriously the challenge of new possibilities and wish to introduce into their work perceptions, ideas and experiences which have come about only within our time.

Though neither Kuspit nor Schapiro claims any special spiritual awareness, they both are keenly aware of what is considered new and what is not - and that is the most important criteria in a commerce driven artworld.

The means by which today's best abstract art achieves its spiritual integrity are the same as they were when abstract art originated, but they are now insisted upon with great urgency: silence and alchemy. Both were already evident in Kandinsky and converged in his sense of "total abstraction" and "total realism" as different paths to the same goal. Total abstraction is a kind of silence: "the diverting support of reality has been removed from the abstract." Total realism is a kind of alchemy: "the diverting idealization of the abstract (the artistic element) has been removed from the objective. . . . With the artistic reduced to a minimum, the soul of the object can be heard at its strongest through its shell because tasteful outer beauty can no longer be a distraction." In both total abstraction and total realism the diverting outer has been eliminated, generating a sense of inner necessity.

Is Kuspit's determination of what is "today's best abstract art" and its "spiritual integrity" based on his own critical judgment and sense of spirituality?

Is he really claiming aesthetic and spiritual authority?

More likely, we are just supposed to accept this as common knowledge among the well educated. (to whom we would like to belong)

Abstract Expressionism was in crisis by the late 1950’s - and perhaps economics had made "spiritual,integrity" an issue for it’s superstars as well as those who emulated their success. But weren’t there still artists who were in it to find and express what was most important to them, not the art market? The problem was that big money had begun looking elsewhere - and so art critics had to as well.

Kandinsky's text (in English) is as follows

(taken from On the Question of Form in the Blue Rider Almanac )

These two elements have always existed in art. They have been matter by the spirit can easily be classified between two poles.

These two poles are:

1. Total abstraction

2. Total realism .

These two poles open two ways that lead ultimately to one goal. Between these poles lie many combinations of the different harmonies of abstraction and realism. These two elements have always existed in art. They have been classified as the “purely artistic” and the “objective.” The first was expressed in the second while the second was serving the first. It was a fluid balance, which seemed to search for its ideal fruition in an absolute equilibrium.

It seems that this ideal is no longer a goal today. The horizontal bar that held the two pans of the scale in balance seems to have vanished today; each pan intends to exist individually and independently. This breaking of the ideal scale also seems to people to be “anarchistic’ Art has apparently brought to an end the pleasant supplementing of the objective by the abstract, and vice versa. On the one hand, the diverting support of reality has been removed from the abstract, and viewers think they are floating. They say that art has lost its footing. On the other hand, the diverting idealization of the abstract (the “artistic” element) has been removed from the objective; and viewers feel nailed to the floor. They say that art has lost the ideal. These reproaches originate in incompletely developed feeling. The custom of concentrating on form and the resultant behavior of the viewer who clings to the accustomed form of balance are the blinding forces that block free access to free feeling.

The emergent great realism is an effort to banish external artistic elements from painting and to embody the content of the work in a simple (“inartistic”) representation of the simple solid object. Thus interpreted and fixed in the painting, the outer shell of the object and the simultaneous canceling of conventional and obtrusive beauty best reveal the inner sound of the thing. With the “artistic” reduced to a minimum, the soul of the object can be heard at its strongest through its shell because tasteful outer beauty can no longer be a distraction. (The spirit has already absorbed the content of conventional beauty and no longer finds new nourishment in it. The form of this conventional beauty gives conventional enjoyment to the lazy physical eye. The effect of the work is mired in the field of the physical. Spiritual experience becomes impossible. Often this beauty creates a force that leads not to the spirit but away from it.)

This is possible only because we can increasingly hear the whole world, not in a beautiful interpretation, but as it is. The “artistic” reduced to a minimum must be considered as the most intensely effective abstraction. ( The quantitative reduction of the abstract therefore equals the qualitative intensification of the abstract. Here we touch one of the most essential rules: the external enlargement of a means of expression leads under certain circumstances to a reduction of its internal power.

Here 2 +1 is less than 2 - 1. This rule is naturally also revealed in the smallest forms of expression: a spot of color often loses intensity and must lose effect by being enlarged and made more powerful. An especially active movement of color is often produced through restraint; a mournful sound can be achieved by direct sweetness of color, and so on. All these are expressions of the law of antithesis and its consequences.

The great antithesis to this realism is the great abstraction, which apparently intends to annihilate the objective (reality) and to embody the content of the work in “incorporeal” forms. Thus interpreted and fixed in the painting, the abstract life of representational forms is reduced to a minimum and best reveals the inner sound of the painting. Likewise, as in realism the inner sound is intensified by blotting out the abstract, so in abstraction this sound is intensified by blotting out reality. In realism conventional outer, tasteful beauty is a limitation; in abstraction the conventional, outer, supporting object is a limitation.

In order to “understand” this kind of painting, the same kind of liberation is necessary as in realism. That is, here also it must become possible to hear the whole world as it is without representational interpretation. Here these abstracting or abstract forms (lines, planes, dots etc) are not important in themselves but only their inner sound, their life. As in realism, the object itself or its outer shell is not important, only its inner sound, its life.

The “representational” reduced to a minimum must in abstraction be regarded as the most intensely effective reality. (At the other pole we meet the same previously mentioned law whereby quantitative reduction equals qualitative intensification.)

In conclusion: in total realism the real appears strikingly great and the abstract strikingly small; in total abstraction this relation seems to be reversed, so that in the end these (= aim) two poles are equalized.

Between these two antipodes we can put the equals sign:

Realism = Abstraction

Abstraction = Realism

*********

Why didn’t Kandinsky offer any examples of "total realism" or "total abstraction" ?

I’m guessing that his own non-objective paintings exemplify "total abstraction"

But what about "total realism" ?

Kandinsky's writing may be the place where theories of non-objective painting begins. He was well educated, articulate, and a great painter ( an opinion I share with the art history books ). But his writing is still entangled with the aesthetics of narrative and mimetic painting from previous centuries. Kuspit presents, and sometimes mis-represents, it as some kind of iconic, fundamental understanding of this new kind of painting

Kandinsky is also entangled with a hierarchical notion of spirituality appropriate for institutions like the Orthodox or Roman Catholic church. Kuspit goes along with that, though I doubt he's very firm in his belief. He certainly does not elaborate as Kandinsky did. It's a notion that needs to be examined - and probably abandoned as well. Humans are spiritual creatures - and at least regarding our response to art - I'm not sure that spiritual hierarchies apply anywhere near as much as experience. Those who see a lot of non-objective paintings are more likely to relate to them.

Would a nearly artless symbol of "chair", like the one drawn above, be more or less "totally real" than this highly detailed, but unrecognizable, photo of the chair on which I am now sitting ?

"Realism" is only a stated goal for those who are unaware that the human perception of it is seamlessly interwoven with cognition, emotion, language, history, and a bunch of other stuff I'm too lazy to enumerate.

Perhaps Kandinsky neglected to show us examples of "total realism" because he knew they could only confuse things even more.

Now if "realism" were tethered to a testable recognizability of things in the visible world - and "abstraction" tethered to aesthetic pleasure -- a reasonable, and familiar,set of polarities might be considered. But it could not be applied to non-objective painting --which can certainly feel more or less real -- but only in a personal way. Had Kandinsky been more familiar with Chinese art, his two polarities might have been the Taoist ones: a single point, infinitely small versus a vast ever-emerging universe with no limit.

Abstract art must pursue ever more complicated ways of becoming silent. Schapiro noted that Kandinsky was aware of the difficulty of achieving silence, which in part explains his shift from gesture to geometry, which seemed quieter. In 1931 Kandinsky wrote: "Today a point sometimes says more in a painting than a human figure. . . . The painter needs discreet, silent, almost insignificant objects. . . . How silent is an apple beside Laocoön. A circle is even more silent. "

I saw several late Kandinsky

in a special exhibit in Milwaukee and found them flat, fussy, dry and tedious. As Kuspit has recognized, he was indeed a precursor to the minimalism of fifty years later.

Agnes Martin, Untitled #12, 1977, 72 x 72". (My selection)

]

Many abstract artists have increased silence by abandoning even geometry, except for the minimal geometry of the canvas shape, which is sometimes echoed in the order of a grid, as in works by Agnes Martin. Touch itself exists under enormous constraint; it often becomes increasingly inhibited.

I suppose the big thrill here is to look for something happening and never finding it - like looking at a corpse of someone you loved and waiting for it to move.

James Terrell, Alta (pink), cross corner projection, dimensions variable, 1968

(My selection)

As Adorno wrote,

"The more spiritual works of art are, the more they erode their substance." In the case of Robert Irwin and James Turrell the works seem almost substanceless. Silence can be understood as the eroded substance of the completely spiritual work of art.

Note that neither of above are paintings.

Isn’t this book about abstract painting?

Mattias Grunewald, 1515, 55 x 105"

Would Kuspit/Adorno consider this substance less… or just not very spiritual?

Or are they only talking about a certain, special 20th century artworld kind of spirituality?

*********

BTW —- Irwin started out as an abstract expressionist:

Robert Irwin, Ocean Park, 1960-61, 65 x 65"

(My selection)

Sure doesn’t feel silent to me — more like loud and grating

..like chalk on a blackboard.

I love it’s hectic, awkward, hesitant anxiety,

and far prefer it to his later ethereal work.

But who can blame an artist for cultivating bliss instead of anxiety?

And in 1960, the clearest path to art world glory

no longer led through abstract expression

It reminds me of the characters in

Su Shih’s "Cold Food Observance"

************

Joseph Beuys, Fat Chair, 1964-85

(My selection)

The alchemical approach offers a different way of using abstract art to articulate the spiritual. By converting material, even the most random and outrageous material, into the "mystical inner construction" of art, the artist gives the material inner meaning and thus uses it to generate spiritual atmosphere. This is less destructive of art itself, using its material nature to extend its spiritual possibilities rather than obliterating both. The alchemical approach emphasizes art's transformative power. Art has not only the power of transforming materials by locating them in an aesthetic order of perception and understanding but also of transforming the perception and understanding of different kinds of being by making explicit their hidden connection. Both silence and alchemy are spiritual in import, but where silence is an articulation of the immaterial, alchemy is a demonstration of the unity of the immaterial and the material.

Joseph Beuys said that "man does not consist of chemical processes, but also of metaphysical occurrences. ". Alchemical abstract art can be understood as a place of major metaphysical occurrences, as a spiritual place. Abstract art as an alchemical-spiritual-izing process, however, is a means, not of offering disguised imagistic support to religious dogmas, but of exploring the possibilities of "bringing together what has come apart," as Bruno Ceccobelli put it.

Alchemical abstraction attempts to evoke a sense of unity. In alchemical abstraction formal contrast is read as metaphysical unity, and every pictorial element becomes subliminally symbolic.

The abstractions of silence and of alchemy converge in their common pursuit of what Ernst Cassirer called "symbolic pregnance," their gnosticism. The picture produces "a sensory experience (which] by virtue of the picture's own immanent organization, takes on a kind of spiritual articulation. ". The symbolic pregnance, which the abstract work is experienced as possessing, returns perception to "zero-degree" appearance, on the order of Roland Barthes's "zero-degree writing"; the work as a whole is read spiritually rather than empirically.

Joseph Beuys, Blue on Center, 1984, painted metal on card

(Kuspit’s selection from the exhibition)

This piece was the example included with the text. It’s more like a painting than Fat Chair - though it’s really just an assembly of things. It’s lifeless visuality is the point. It’s a world away from how Josef Albers calibrated the tones of two squares.

Beuys was no more a painter than Irwin and Terrell had become.

Both "silence" and "alchemy" have been exemplified by non-paintings.

\

Mark Rothko, Number 11, 1949, 68 x 43"

(Kuspit’s selection, not from exhibition)

What this means was indicated by Max Kozloff, who pointed out, writing about Mark Rothko's version of silent painting that it is necessary "to find that lever of consciousness which will change a blank painted fabric into a glow perpetuating itself into the memory." Without this lever there is no reason to "believe the suspicion that he [Rothko] is but the creator of pigmented containers of emptiness. "

The "lever of consciousness" is not so difficult to find if it’s contextual, not visual. The blank fabric hangs on the wall of an art gallery not from a clothesline in your backyard. And so you will query "why is this important?" .. to the degree you respect that institution.

The problem was put another way by Michel Conil-Lacoste,

who remarked that there are'

"two readings of

Rothko: not only the technician of color, but also the engaged heart of mysticism. "As Kozloff said, only when "the spectator himself, growing more intent on the color vibrations [of Rothko's paintings], learns to discount the surface, [so that] the whole painting ceases to be, as a concrete thing," does its

"mystical" or "spiritual" character, its "tran-scendental beauty," become evident. This beauty is materially actualized as color, but color itself becomes a transcendental experience, acquires symbolic pregnance, when it seems immaterial and thereby all the more immediate. What Yves Klein called the "mystical system" of "universal impregnation of color" is central to the effect of transcendental immediacy or symbolic pregnance in much silent painting. When Marc spoke of the abstract work as a "mystical inner construction," in effect he was speaking of its power to ecstatically convert the empirically given into the transcendent.

Lucy Lippard noted that the tradition of silent painting, or "monotonal paintings" of " 'empty' surface," has no "nihilistic intent. " Their emptiness is really a form of spiritual.

The Rothko at the Smart Museum in Chicago has an empty surface — and I find it boring. The example chosen for this essay (shown above ) has some rhythm, contrast and harmony.

I would have preferred to read how Kuspit himself felt in front of these pieces as he writes about their spirituality. That way his feelings and theory might explicate each other. Instead he just offers very short quotes from those who qualify as quotable ( Marc, Klein, Kozloff, Camille-Lacoste) - with zero original context

Ad Reinhardt, untitled, 1964 (my choice)

Lucy Lippard noted that the tradition of silent painting, or "monotonal paintings" of "'empty' surface, " has no "nihilistic intent. "Their emptiness is really a form of spiritual expression:

The ultimate in monotone, monochrome painting is the black or white canvas. As the two extremes, the so-called no-colors, white and black are associated with pure and impure, open and closed. The white painting is a "blank" canvas, where all is potential; the black painting has obviously been painted, but painted out, hidden, destroyed. An exhibition of all-black paintings ranging from Rodchenko to Humphrey to Corbett to Reinhardt, or an exhibition of all-white paintings, from Malevich to Klein, Jusama, Newman, Francis, Corbett, Martin, Irwin, Ryman, and Rauschenberg would be a lesson to those who consider such art "empty. "

In this context one recalls Ad Reinhardt's insistence that "you can only make absolute statements negatively, " a statement that is inseparable from the basic understanding of abstraction as negation. Reinhardt connected his own painting with " long tradition of negative theology in which the essence of religion, and in my case the essence of art, is protected or the attempt is made to protect it from being pinned down or vulgarized or exploited. For Reinhardt the "square, cruciform, unified absolutely clean mandala shape he utilized in his famous "black," or negative, paintings serves the same purpose as Rothko's "disembodied chromatic sensations,

" namely, to preserve the spiritual atmosphere. While, as Lippard noted, some artists, such as Barnett Newman, welcome spiritual "symbolic or associative interpretation" and others are "vehemently opposed to any interpretation and deny the religious or mystical content often read into their work as a result of the breadth and calm inherent in the monotonal theme itself, »35 there is no denying the numinous effect generated by the negativity of silent abstraction. The silent painting, contemplated in a more than casual way, has a numinous effect simply by reason of its radical concreteness, its unconditional immediacy. This can be iconographically interpreted or not, but it is functionally mystical - that is, it is not the vehicle of communication of religious dogma but of a certain kind of irreducible, nondiscursive experience.

Many of the silent painters who refuse their work an overt religious meaning are afraid that their art will be appropriated by a belief system, becoming a dispensable instrument of faith rather than an end in itself. It will thereby lose the full power of its negativity.

The question of religious belief is separate from the question of spiritual experience, which is what silent painting engages.

In response to Lucy Lippard, why can’t we say that Nihilism is also a form of spiritual expression? It need not be materialistic. This is one more reason why this discussion needs an elaboration on "spirituality" by those who use the term.

The contemplation of nothingness is crucial in some meditative practices, including my own, but why does it need an artist to be enabled? Would anyone seriously claim that it can only be experienced in an art gallery? It might take some practice, but the meditative process is quite simple.

So if these pieces aren’t really necessary for the experience of emptiness - why are some of them so expensive to buy? Luxury goods, as Shapiro calls them. Aren’t they delivering something far more important to those involved? And doesn’t a word like "status" apply? - a status that has been created, for their own self interest, by dealers, critics, and buyers. The artists aren’t really that important because anyone can paint a black square.

Alfred Jensen, A Fire Ringed the Earth, 1961, 22 x 28"

(Kuspit’s selection, not from the exhibition)

Alfred Jensen, My Oneness, a Universe of colors, 1957

(Kuspit’s selection, not from the exhibition)

Alfred Jensen, Galaxy I and Galaxy II, oil on canvas, 46 x 80"

(My selection)

I

The question of religious belief is separate from the question of spiritual experience, which is what silent painting engages.

Silent abstract painting works through its holistic effect. It seems to articulate an irreducible unity, one that survives any attempt to differentiate it. In the painting of mandalas, this unity remains but is communicated through finite forms that acquire symbolic import. The symbolic in this context is a kind of borderline between the communicative and the spiritual, in the sense of Schapiro's distinction. The symbol is a kind of limit of materiality and as such an approach to the immaterial. It offers as much communincation, as much of a prepared and complete message, as the abstract spiritual painting allows. The problem with the spiritual symbolism used by such painting is that it tends to become a communicative cliché by reason of its cultural familiarity or traditional character or else tends not to communicate spirituality at all, simply becoming a boring, empty shape. Symbolic spiritual art, a communicative extension of silent painting, must dramatize (respiritualize, revitalize) the forms it use to make them spiritually convincing. It does this by fusing their eternal character with a worldly content that is shown to have mystical import, inner meaning. This interaction and reconciliation generates spiritual atmosphere.

Kenneth Noland, Beginning, 1958

(My selection)

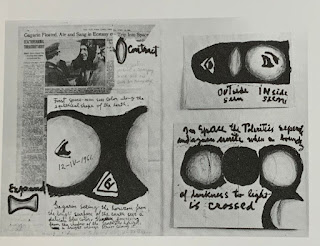

Alfred Jensen's work accomplishes this in an exemplary way. Jensen, an avowed mystagogue, established a correlation between the mandala-diagram forms he used and actual events of the contemporary world, events that bespeak spiritual reality. With great daring, he united the technological and spiritual worlds, usually thought of as impossibly at odds. Thus his painting A Film Ringed the Earth, 1961 (pl. 9), deals with the first space flight as a spiritual event on the borderline between the physical and metaphysical, alchemically synthesizing the two in the person of the first astronaut, the Russian Yuri Gagarin. The work brings together the New York Times article on the flight and Jensen's diagrams of some of the "visions" it produced.

The newspaper headline-

"Gagarin Floated,

Ate and Sang in Ecstasy on Trip into Space"

- describes the event. The handwritten headlines -

"In space the polarities separate and again unite when a boundary of darkness to light is crossed"; "First space-man sees color along the spherical space of the earth"; "Gagarin seeing the horizon from the bright surface of the earth sees a delicate blue color. Gagarin emergeing [sic] from the shadow of the earth sees the horizon a bright orange strip along it"

-suggest the event's spiritual significance.

Color is ecstatically perceived, where ecstasy has the weight of its original etymological meaning, a standing-out: the perception of the dynamic in the static. Jensen identifies with Gagarin and recreates what is for Jensen the most essential aspect of Gagarin's experience: the lyricism of perception in space. This lyricism involves the direct experience of color as an oscillation between poles. The direction of the movement determines the very nature of the color as well as its quality.

Reading the text on Jensen’s website, it’s a stretch to call him a mystagogue. Through his distinguished teachers (like Despiau) he primarily saw himself firmly in the tradition of European art. He felt a strong emotional attachment to the sun - the source all those photons a visual artist must affect - but he professed no doctrine of spiritual development. The above collage locates Man in an astronomical universe - not a mythic one. He responded to the seen - not the unseen.

I’ve selected two of his pieces( Galaxy I and II ) that demonstrates his achievement as an abstract painter. I would call it a powerful portrait of existence. It does have an aesthetic spirituality for me - but hardly a doctrinal one. Kuspit did not discuss the "Circumpolar Journey", the only piece that was included in this exhibition. The image shown below suggests that visual impact has been sacrificed to to some kind of personal obsession.

I’ve also shown a circular piece by Kenneth Noland. Kuspit mentions but does not elaborate on his work - which feels more artsy/flamboyant and less personal than Jensen’s.

This painting is Jensen's spiritual credo and links with an earlier credo, My Oneness: A Universe of Colors, 1957. This work surrounds a tantric circle mandala, not unrelated to those painted by Kenneth Noland around the same time, with two boldly written words -

"Self-Identity" and

"Self-Integration"

- and two quotations:

"So we'll live and pray and sing and tell old tales and laugh at gilded butterflies" (William Shakespeare) and "No repeated group of words would fit their rhythm and no scale could give them meaning" (Nathanael West).

Self-identity and self-integration are the "gilded butterflies" that can never be captured in a net of words, for no words nor scale of meaning can fit or measure them.

m Jensen's way of working seems applicable to many successful mandala-diagram, or symbolically spiritual, types of painting. The use of vibrant color, the sense of empirical events that are inherently spiritual, and the emphasis on the ecstatic experience of the self leading to an identification of the abstract-symbolic work with the self- all of this is central to an understanding of the symbolic spiritual painting.

m Jensen's way of working seems applicable to many successful mandala-diagram, or symbolically spiritual, types of painting. The use of vibrant color, the sense of empirical events that are inherently spiritual, and the emphasis on the ecstatic experience of the self leading to an identification of the abstract-symbolic work with the self- all of this is central to an understanding of the symbolic spiritual painting.

This piece feels so awkward and banal --

I don't especially want to identify with it.

Whether or not Jensen did does not concern me.

What is pursued in Jensen's paintings is pursued in most significant symbolic spiritual paintings: the achievement of integration out of which a sense of identity or self emerges. That viewing experience comes from a complex physical integration of the material of the work and the symbol, as well as of the symbol and its exemplification. The dynamics of this integrative process are crucial, for the symbol is already an integrated form. The symbol is given a fresh sense of ecstatic immediacy by the dynamic materiality that gives it new body.

This piece, chosen by Kuspit from outside the exhibition,

begins to clarify what he wants out of symbolic spiritual paintings:

1. it has text,

2. it is broadly rather than specifically symbolic,

3. it is loosely executed in both drawing and color.

The text suggests profundity and learning,

while the image invites the viewer to provide meaning

rather than proclaiming one in a convincing manner.

Kuspit also tells us that

"Jensen makes explicit the issues of self-identification

and

self-integration that are latent in the meaning of the spiritual today"

He offers no footnote concerning "the meaning of the spiritual today" so presumably that is his own observation - but based on what? Anything more specific than his own life experience and the people he knows?

Here’s a do-it-yourself mandala kit on Amazon.

The mandala shown is quite different from Jensen’s.

More feminine - intensely so

Less crude - more highly finished

Losing the sense of sincere searching

Gaining a sense of perfection, sophistication, elegance.

Is it any less true that: " The symbol is given a fresh sense of ecstatic immediacy by the dynamic materiality that gives it new body". ?

Neha Deoliya, Found on

ColorsandSmiles.com

And here’s "an ambitious and passionate digital marketer" from Australia who paints mandalas and teaches others as well.

She calls herself "an ordinary girl with an ordinary story"

But doesn’t the above have its own "fresh sense of ecstatic immediacy"?

At least it probably did for her.

And finally, here’s a fractal mandala.

There’s an eerie coldness about images generated by numbers.

If the Jensen mandala were included in an international exhibit, perhaps it’s freshness and intensity would stand out. But who knows? That would be a good reason to mount such an exhibit

Dorothea Rockburne. Saqqarah, 1972 , 69 x 93, oil and gesso on canvas

(Kuspit’s selection from exhibition)

Perhaps the most uncomplicated , naturally available mandala is the golden section: a relationship of two parts to a whole in which the ratio of the smaller part to the larger is the same as the ratio of the larger part to the whole. This mystical proportion, existing beyond invention, is usually not understood as a mandala, but that is exactly what it is.

Reading through the extensive Wikipedia entry for "mandala", every single example from meditative traditions worldwide, features radial symmetry - which the Rockburne does not. So how does it qualify?

The above piece feels very uncomfortable to me - even if the larger triangles are 1.618 times the size of the smaller ones.

Sheba

While this piece, from the same series, feels far more enjoyable

(My selection)

Dorothea Rockburne's work is dominated by an increasingly coloristic articulation of the golden section:

One of its aspects that makes the Golden Section so fascinating to Rockburne is the correspondence it suggests - for example, the musical chord that seems most satisfying to the ear - the major sixth

- vibrates at a ratio that approximates the Golden Section. The same ratio is equal to the relationship between any two numbers of the Fibonacci numbering system, invented by a thirteenth-century Italian mathematician. In turn, the Fibonacci numbering system is the basis for such diverse

"systems" as the spiral patterns in certain types of pine cones and the spiral shells of certain sea creatures.

All of these correspondences fascinate the artist, and she has said that working with the proportions of the Golden Section is magical for her. The proportions give the magic as she puts them together.

Love that quotation from Sartre which asserts the objectivity of taste - while articulating why I need to own certain paintings so I can view them again and again and again - with or without a golden section - or any other mathematical formula.

Though we must note that another online translation from Sartre’s "Being and Non-being" reads "objectifying" instead of "objective" - and that book is not about viewing art at all. So maybe we should attribute the quote to Rockburne. I love it anyway.

This summation reveals much about Kuspit’s approach to spirituality in painting—- it is to be intellectually recognized, not felt — and he wants artists to apply distinct identifiable strategies rather than magnify a unique visual event. That might explain why Kuspit chose pieces that satisfy me far less than other works by the same artist. Visual appeal distracts attention from the strategies that interest him.

For all the sophistication of the mandala users, their goal is an innocent relationship to an ultimate William James offered " 'four marks' of the mystic state, Ineffability, Noetic Quality, Transiency, and Passivity." Evelyn Underhill finding them inadequate, proposed four alternative "rules or notes which may be applied as tests to any given case"

1. True mysticism is active and practical, not passive and theoretical. It is an organic life-process, something which the whole self does; not something as to which its intellect holds an opinion.

2. Its aims are wholly transcendental and spiritual. It is in no way concerned with adding to, exploring, rearranging, or improving anything in the visible universe. The mystic brushes aside that universe, even in its supernormal manifestations. Though he does not, as his enemies declare, neglect his duty to the many, his heart is always set upon the changeless One.

4. Living union with this One - which is the term of his adventure - is a definite state or form of enhanced life. It is obtained neither from an intellectual realization of its delights, nor from the most acute emotional longings. Though these must be present, they are not enough. It is arrived at by an arduous psychological and spiritual process - the so-called Mystic Way - entailing the complete remaking of character and the liberation of a new, or rather latent, form of consciousness; which imposes on the self the condition which is sometimes inaccurately called "ecstasy," but is better named the Unitive State.

Kuspit finally turns to Evelyn Underhill (1875-1941) to define what he means by spirituality - though he does seem to have difficulty with following rule #4 - at least regarding spirituality in art. Kuspit is all about an intellectual rather than aesthetic understanding . We may note that the Underhill rules may well point to one who sincerely searches for spirituality - but not so much toward one who has found and can present that strange other world that coexists with the one we all know.

Applying Underhill's criteria to abstract art that claims to articulate the mystic state, one recognizes that while most works do not satisfy all the criteria, many satisfy one or more, suggesting that they articulate not only aspects of the mystic state but also the process of realizing it. Many of the paintings that seem to show "heart" through their immersion in color also use it to create the silence that renounces the visible universe, to wipe out "the many," except in the residual form of

color differences and nuances of tone within a single color. The alchemical-symbolic paintings seem concerned to force, not simply evoke, latent consciousness of the unitive state. Holistic works in general seem to symbolize it as concretely as possible, as if the materialization of oneness could produce on demand latent consciousness of it. All of these works attempt to renew art as a mystical process and show that the work of art can function as a surrogate absolute reality.

How can we know what a painting is claiming ? The 16th C. Gruenwald painting shown earlier in this post has a sacred subject matter that almost any adult can identify. It was painted to go above an altar in a place of worship. That piece claims to present the spiritual world - the mystic state — and I’m not the only one who feels it’s quite convincing.

Non-objective art leaves interpretation up to viewer and location up to the owner.

Some visual art -especially political cartoons - were meant to function like a verbal proposition. But non-objective painting functions differently.

Bill Jensen, Guy in the Dunes, 1979, 36 x 24

(Selected by Kuspit from the exhibition)

This piece feels to me like it is tearing a hole in the natural world to reveal the great mystery of nothingness

But that’s just me — the title seems to suggest something quite different.

Bill Jensen, Locus, 39 x 32, 2001-3

(Selected by me)

Another amazing painting by Bill Jensen - I am so glad Kuspit chose to show him.

This one feels to me like a community of Hasidim dancing at a wedding. ( Jensen’s studio is in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn). But again - that’s just me — and it’s definitely not any symbolism that makes me feel that way. The piece is so ecstatic, I want to jump up and dance myself.

Morris Graves, Hibernation, 1954, 18 x 26"

(My selection)

Graves was a fascinating loner who took his art in many directions.

I selected this piece because I like it.. and it contains a mandala.

It depicts a hibernating mink - but it could just as well be the egg of any living thing - and it’s connection to the otherworldly energy that will bring it to life.

Mark Tobey, Written Over the Plains, 30 x 40, 1950

(My selection)

This seems to continue the intense, all-over tradition begun by Kandinsky in pieces like the one shown at the top of this post. It seems to present the amazing complexity of interrelationship among the unseen forces that impact our existence.

An incomprehensible order - but an order nonetheless.

The many abstract works show an "active and practical" process of working through the empirically given to the spiritually articulate.

(This is not the same as Alfred Jensen's synthesis of the empirical and the spiritual.) On the one hand, there are works that attempt to articulate the mystic state by working through the appearances of nature toward a unified symbol of the supernatural. The works of Morris Graves, Mark Tobey, and more recently Bill Jensen are important examples.

All figurative work - when it's good enough to be called art - also synthesizes the empirical and the spiritual. (where "spiritual" is broadly defined as that forward, upward inner need of which Kandinsky wrote)

Yves Klein, Cosmogeny series, Le Vent du Voyage, 1961, 36 x 29, acrylic on canvas

(Kuspit’s selection from exhibition)

Yves Klein, Untitled blue monochrome (IKV 69) 1959

(Kuspit;s selection from exhibition)

Klein’ s father was a late Impressionist - his mother was was mid-century modernist - and that accounts for the painterliness of the Cosmogony series. But he also wanted to be recognized as contemporary - and that accounts for his Klein Blue installations.

Bruno Ceccobelli, Etrusco Ludens, 1983

(Kuspit’s selection from the exhibit)

Eric Orr, Crazy Wisdom, 1982, lead, gold leaf, human skull bone,

blood, crushed am/fm radio on linen, 43 x 32

(Kuspit’s selection from the exhibit)

A nice pattern - regardless of materials.

On the other hand, there are works that attempt to evoke a sense of the prehistorical, a primitive state that becomes emblematic of the mystic state. Eric Orr and Bruno Ceccobelli ,in their very different ways, are major examples. In both kinds of work the artist is attempting to function shamanistically.

Are they successful as actual shamans (which have no role in our society ) or just in pretending to be one for the sake of a career in the contemporary artworld? Are they even painters? (Orr was not)

***********

The most important function of the art critic, in my view, is to introduce artists we’re glad to discover. So now, thanks to this essay, my bucket list includes seeing paintings by Bill Jensen. Hopefully, I won’t have to travel to New York - but I doubt any Chicago area Institution will show him in my lifetime. Old, educated, East Coast white guy who makes visionary abstract paintings ? Not likely.

The second most important function of the critic is to put art into context - and for this catalog, that context is spirituality in 20th century abstract painting. As Kuspit sees it, as abstract painting proliferated, it lost its spiritual roots (Kandinsky) and can only evoke spirituality by using certain strategies - which often involves doing something other than painting.

So Kuspit is kind of rebelling against the presumed premise of this catalog: concerning the spiritual in abstract painting —- often it isn’t there. Perhaps that’s because the concept of spirituality is about as outdated as abstract expressionism. It’s backward looking - so much so, that when Kuspit looks for an authoritative definition, he turns back to William James and Evelyn Underhill. It’s not a subject that concerns more contemporary thinkers like Derrida or Lacan.

It would have been helpful if Kuspit had told us more about non-spiritual abstract painting. Is it all "a predictable aesthetic experience, impersonally transmitted" ? If so, can it have any good qualities as well that make it compelling?

But compelling visuality, spiritual or not, doesn’t seem to interest him anywhere near as much as whatever concepts can be used to celebrate renowned contemporary art. That might serve as the job description for any contemporary art critic.

******

As I look through the non-objective painters I collect or follow on Instagram, they all feel spiritual - in the most general way of being about someone’s inner life. How can a good painting not feel that way? None of them feel aligned with any specific spiritual tradition. None of them feel like they come from another dimension - a distinct world of the spirit. They all have one foot firmly planted in our ordinary world - even if the other foot is stretching out to touch somewhere else - both higher and deeper.

One final note: I don’t yet know the scope of the other essays in the catalogue - but this essay should have been re-titled as "Concerning the Spiritual in Abstract American and Western European Art". The rest of the world has been ignored.