Saint Apollinaris, San Vitale, Ravenna

Empress Theodora, San Vitale, Ravenna

Durer, "Lamentation", 1500

(the above illustrations were included in the 1946 edition,

The original 1911 edition only contained 11 woodcuts by Kandinsky himself)

Part One: General Aesthetic

I. Introduction

The essay begins with ideas already presented in the Almanac -- the bad old materialist age versus the new

age of the spirit.

After the period of materialist effort, which held the soul in check until it was shaken off as evil, the soul is emerging, purged by trials and sufferings. Shapeless emotions such as fear, joy, grief, etc., which belonged to this time of effort, will no longer greatly attract the artist. He will endeavour to awake subtler emotions, as yet unnamed. Living himself a complicated and comparatively subtle life, his work will give to those observers capable of feeling them lofty emotions beyond the reach of words.

Now he's trying to clarify his notion of spirituality -- it's too bad these "subtler emotions" must remain unnamed.

Would 'awe' have been included?

Corot, Nymphs and Fauns, before 1870 (detail)

The observer of today, however, is seldom capable of feeling such emotions. He seeks in a work of art a mere imitation of nature which can serve some definite purpose (for example a portrait in the ordinary sense) or a presentment of nature according to a certain convention ("impressionist" painting), or some inner feeling expressed in terms of natural form (as we say—a picture with Stimmung) [Footnote: Stimmung is almost untranslateable. It is almost "sentiment" in the best sense, and almost "feeling." Many of Corot's twilight landscapes are full of a beautiful "Stimmung." Kandinsky uses the word later on to mean the "essential spirit" of nature.—M.T.H.S.] All those varieties of picture, when they are really art, fulfil their purpose and feed the spirit. Though this applies to the first case, it applies more strongly to the third, where the spectator does feel a corresponding thrill in himself. Such harmony or even contrast of emotion cannot be superficial or worthless; indeed the Stimmung of a picture can deepen and purify that of the spectator. Such works of art at least preserve the soul from coarseness; they "key it up," so to speak, to a certain height, as a tuning-key the strings of a musical instrument. But purification, and extension in duration and size of this sympathy of soul, remain one-sided, and the possibilities of the influence of art are not exerted to their utmost.

Since both of the art museums in Cincinnati have such good Corot's, I've been in contact with this kind of "stimmung" for over 50 years.

I find it impossible to measure qualities of 'purification' and 'sympathy of soul' - and have no idea how they might be considered 'one-sided". What other sides are there ?

Imagine a building divided into many rooms. The building may be large or small. Every wall of every room is covered with pictures of various sizes; perhaps they number many thousands. They represent in colour bits of nature—animals in sunlight or shadow, drinking, standing in water, lying on the grass; near to, a Crucifixion by a painter who does not believe in Christ; flowers; human figures sitting, standing, walking; often they are naked; many naked women, seen foreshortened from behind; apples and silver dishes; portrait of Councillor So and So; sunset; lady in red; flying duck; portrait of Lady X; flying geese; lady in white; calves in shadow flecked with brilliant yellow sunlight; portrait of Prince Y; lady in green. All this is carefully printed in a book—name of artist—name of picture. People with these books in their hands go from wall to wall, turning over pages, reading the names. Then they go away, neither richer nor poorer than when they came, and are absorbed at once in their business, which has nothing to do with art. Why did they come? In each picture is a whole lifetime imprisoned, a whole lifetime of fears, doubts, hopes, and joys.

Why must we assume that none of these viewers have been touched by those "whole lifetimes of fears, doubts, hopes, and joys "? Might not that be why some people set aside their daily business and visit an art museum ?

Whither is this lifetime tending? What is the message of the competent artist? "To send light into the darkness of men's hearts—such is the duty of the artist," said Schumann. "An artist is a man who can draw and paint everything," said Tolstoi.

Must these messages be mutually exclusive ?

Of these two definitions of the artist's activity we must choose the second, if we think of the exhibition just described. On one canvas is a huddle of objects painted with varying degrees of skill, virtuosity and vigour, harshly or smoothly. To harmonize the whole is the task of art. With cold eyes and indifferent mind the spectators regard the work. Connoisseurs admire the "skill" (as one admires a tightrope walker), enjoy the "quality of painting" (as one enjoys a pasty). But hungry souls go hungry away.

What is the source of an appetite for harmony or virtuosity ? If it's not in the mind or soul -- where is it?

The vulgar herd stroll through the rooms and pronounce the pictures "nice" or "splendid." Those who could speak have said nothing, those who could hear have heard nothing. This condition of art is called "art for art's sake." This neglect of inner meanings, which is the life of colours, this vain squandering of artistic power is called "art for art's sake."

And yet Kandinsky cannot tell us about these 'inner meanings' either.

The artist seeks for material reward for his dexterity, his power of vision and experience. His purpose becomes the satisfaction of vanity and greed. In place of the steady co-operation of artists is a scramble for good things. There are complaints of excessive competition, of over-production. Hatred, partisanship, cliques, jealousy, intrigues are the natural consequences of this aimless, materialist art.

It's more like the natural consequence of being human. As "The Name of the Rose" suggests, the same is true among monks in a monastery

Sympathy is the education of the spectator from the point of view of the artist. It has been said above that art is the child of its age. Such an art can only create an artistic feeling which is already clearly felt. This art, which has no power for the future, which is only a child of the age and cannot become a mother of the future, is a barren art. She is transitory and to all intent dies the moment the atmosphere alters which nourished her.

The other art, that which is capable of educating further, springs equally from contemporary feeling, but is at the same time not only echo and mirror of it, but also has a deep and powerful prophetic strength.

The spiritual life, to which art belongs and of which she is one of the mightiest elements, is a complicated but definite and easily definable movement forwards and upwards. This movement is the movement of experience. It may take different forms, but it holds at bottom to the same inner thought and purpose.

What are the identifiable characteristics of a 'deep and powerful prophetic strength'?

An 'Easily definable movement forwards and upwards' might also distinguish art from entertainment---- but can't that also be found in a typical Disney movie?

An 'Easily definable movement forwards and upwards' might also distinguish art from entertainment---- but can't that also be found in a typical Disney movie?

Veiled in obscurity are the causes of this need to move ever upwards and forwards, by sweat of the brow, through sufferings and fears. When one stage has been accomplished, and many evil stones cleared from the road, some unseen and wicked hand scatters new obstacles in the way, so that the path often seems blocked and totally obliterated. But there never fails to come to the rescue some human being, like ourselves in everything except that he has in him a secret power of vision.

He sees and points the way. The power to do this he would sometimes fain lay aside, for it is a bitter cross to bear. But he cannot do so. Scorned and hated, he drags after him over the stones the heavy chariot of a divided humanity, ever forwards and upwards.

Sounds a lot like Christianity. Does any other spiritual tradition center on a teacher who was 'scorned and hated' -- with 'a difficult cross to bear'

Sounds a lot like Christianity. Does any other spiritual tradition center on a teacher who was 'scorned and hated' -- with 'a difficult cross to bear'

Often, many years after his body has vanished from the earth, men try by every means to recreate this body in marble, iron, bronze, or stone, on an enormous scale. As if there were any intrinsic value in the bodily existence of such divine martyrs and servants of humanity, who despised the flesh and lived only for the spirit! But at least such setting up of marble is a proof that a great number of men have reached the point where once the being they would now honour, stood alone.

Sadly, this is an iconoclastic attack on religious statuary -- as well as an assertion that spiritual leaders "despised the flesh"

II. The Movement of the Triangle

Kandinsky then elaborates on the idea of spiritual hierarchy that he offered in the Almanac. Not only is the prophet at the apex above those who are closer to the base -- but the entire structure is moving upward -- like a giant space station - rising ever further from the earth.

And again, he does not offer the possibility of there being more than one triangle moving in different directions.

With all that continuous upward motion, one might expect humanity to be ever more spiritual - from century to century - though something must have gone wrong during the 19th - and the world still seem to be going in the opposite direction.

But despite all this confusion, this chaos, this wild hunt for notoriety, the spiritual triangle, slowly but surely, with irresistible strength, moves onwards and upwards.

The invisible Moses descends from the mountain and sees the dance round the golden calf. But he brings with him fresh stores of wisdom to man.

Here, Kandinsky's iconoclasm is even more explicit. Presumably those "fresh stores of wisdom" are in the form of sacred texts - rather than sacred statues or paintings.

First by the artist is heard his voice, the voice that is inaudible to the crowd. Almost unknowingly the artist follows the call. Already in that very question "how?" lies a hidden seed of renaissance. For when this "how?" remains without any fruitful answer, there is always a possibility that the same "something" (which we call personality today) may be able to see in the objects about it not only what is purely material but also something less solid; something less "bodily" than was seen in the period of realism, when the universal aim was to reproduce anything "as it really is" and without fantastic imagination.

The topic here seems less about the spiritual history of humanity - and more about conflicting ideals in early 20th C. European painting.

[Footnote: Frequent use is made here of the terms "material" and "non-material," and of the intermediate phrases "more" or "less material." Is everything material? or is EVERYTHING spiritual? Can the distinctions we make between matter and spirit be nothing but relative modifications of one or the other? Thought which, although a product of the spirit, can be defined with positive science, is matter, but of fine and not coarse substance. Is whatever cannot be touched with the hand, spiritual? The discussion lies beyond the scope of this little book; all that matters here is that the boundaries drawn should not be too definite.]

It was probably a good idea for Kandinsky to back away from metaphysics --- though as he does so, the topic of this essay becomes ever more vague.

If the emotional power of the artist can overwhelm the "how?" and can give free scope to his finer feelings, then art is on the crest of the road by which she will not fail later on to find the "what" she has lost, the "what" which will show the way to the spiritual food of the newly awakened spiritual life. This "what?" will no longer be the material, objective "what" of the former period, but the internal truth of art, the soul without which the body (i.e. the "how") can never be healthy, whether in an individual or in a whole people.

THIS "WHAT" IS THE INTERNAL TRUTH WHICH ONLY ART CAN DIVINE, WHICH ONLY ART CAN EXPRESS BY THOSE MEANS OF EXPRESSION WHICH ARE HERS ALONE.

So only an artist can be the voice of the prophet.

Wouldn't Islamic calligraphers be doing exactly that?

I wonder why none were included in the Almanac - even though it included several examples of Egyptian shadow puppets. Kandinsky must have seen at least a few examples.

(note: I think the above example is contemporary. Calligraphy this good, or even better, was probably being made even as Kandinsky was writing this essay)

Sheikh Hamdullah (1436-1520)

III. SPIRITUAL REVOLUTION

This section looks up from the middle segments of the above mentioned spiritual triangle, beginning with:

*mainline religious folks (who are really atheists who "have never solved any problem independently" and "know nothing of the vital impulse of life") - including socialists,

*ordinary scientists (positivists) and artists (naturalists) who are a bit higher than the above --- all of whom have a certain anxiety about that which is still unknown but will be recognized as Truth in the future.

*ground-breaking "professional men of learning" who " boldly attack those pillars which men have set up".

An example would be Madame Blavatsky and the Theosophical Society who look beyond materialistic science.

Presumably this categorization reflects the kind of people that Kandinsky knew personally. Apparently, his connection to Theosophy is under dispute. It is possible, if not likely, that he read the literature but did not study with specific mentors.

The first mentioned of the ground-breaking poets or artists, who "give free scope to the non-material strivings of the soul", is Maeterlinck, who prophetically offers "The gloom of the spiritual atmosphere, the terrible, but all-guiding hand, the sense of utter fear, the feeling of having strayed from the path, the confusion among the guides, all these are clearly felt in his works."

I'm completely unfamiliar with Maeterlinck's work, but Kandinsky tells us that his plays present characters who are "lost in the clouds, threatened by them with death, eternally menaced by some invisible and sombre power." --- within stage sets and dialog that are more symbolic than naturalistic.

Moving over to music, he notes Wagner, then Debussy, Scriabin, and finally Schoenberg as creators of a "spiritual atmosphere", "spiritual impression", or "spiritual harmony". He doesn't tell us which composers are less spiritual -- but I would guess that bouncy, upbeat music would be on that list, so Johann Strauss Jr. might be included

BTW - one might note the breadth of Kandinsky's experience of contemporary culture as he follows literature and music as well as painting.

A parallel course has been followed by the Impressionist movement in painting. It is seen in its dogmatic and most naturalistic form in so-called Neo-Impressionism. The theory of this is to put on the canvas the whole glitter and brilliance of nature, and not only an isolated aspect of her.

Is he referring to Seurat ?

It is interesting to notice three practically contemporary and totally different groups in painting. They are (1) Rossetti and his pupil Burne-Jones, with their followers; (2) Bocklin and his school; (3) Segantini, with his unworthy following of photographic artists. I have chosen these three groups to illustrate the search for the abstract in art.

Rossetti, "Sybilla Palmifera", 1865-70

Rossetti sought to revive the non-materialism of the pre-Raphaelites.

Bocklin, Elysian Fields, 1877

Bocklin busied himself with the mythological scenes, but was in contrast to Rossetti in that he gave strongly material form to his legendary figures.

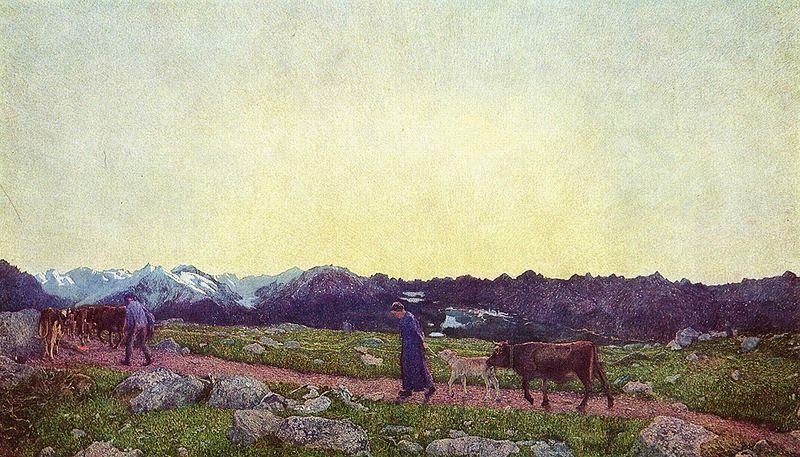

Giovanni Segantini,"Nature", 1898

Segantini, outwardly the most material of the three, selected the most ordinary objects (hills, stones, cattle, etc.) often painting them with the minutest realism, but he never failed to create a spiritual as well as a material value, so that really he is the most non-material of the trio.

I have no idea how Segantini can be considered the "most non-material of the trio" - or how he might be considered more non-material than Daubigny, Courbet, or hundreds of other 19th C. painters. Kandinsky must have felt something that I have not.

Kandinsky tells us that "These men sought for the "inner" by way of the "outer."" -- but what artist does not?

Cezanne, "Buffet", 1877 (detail)

By another road, and one more purely artistic, the great seeker after a new sense of form approached the same problem. Cezanne made a living thing out of a teacup, or rather in a teacup he realized the existence of something alive. He raised still life to such a point that it ceased to be inanimate.

He painted these things as he painted human beings, because he was endowed with the gift of divining the inner life in everything. His colour and form are alike suitable to the spiritual harmony. A man, a tree, an apple, all were used by Cezanne in the creation of something that is called a "picture," and which is a piece of true inward and artistic harmony.

Jean-Etienne Lyotard, "Tea Set", 1781 (detail)

The above example feels just as alive to me - though in a different way.

Matisse, "Still Life with Pineapples" , 1925 (detail)

(I had to show this one because it has a teacup,

though it was painted 13 years after this essay was written)

(I had to show this one because it has a teacup,

though it was painted 13 years after this essay was written)

The same intention actuates the work of one of the greatest of the young Frenchmen, Henri Matisse. He paints "pictures," and in these "pictures" endeavours to reproduce the divine. To attain this end he requires as a starting point nothing but the object to be painted (human being or whatever it may be), and then the methods that belong to painting alone, colour and form.

I wonder whether Matisse himself ever entertained notions of spirituality or the "divine" when working on his paintings.

By personal inclination, because he is French and because he is specially gifted as a colourist, Matisse is apt to lay too much stress on the colour. Like Debussy, he cannot always refrain from conventional beauty; Impressionism is in his blood. One sees pictures of Matisse which are full of great inward vitality, produced by the stress of the inner need, and also pictures which possess only outer charm, because they were painted on an outer impulse. (How often one is reminded of Manet in this.) His work seems to be typical French painting, with its dainty sense of melody, raised from time to time to the summit of a great hill above the clouds.

If only Kandinsky had named an example of each. Certainly, some paintings seem better than others, but I've never felt that contrast between "inner need" and "outer impulse" within Matisse's work, as I've felt it when touring the Chicago Art and Antiques Show - where so much seems to have been made just to satisfy a market.

I like his comment on the "dainty sense of melody" in French painting. The same could not be said about Russian and Eastern European painters - though it could also not be said of so many noted French painters as well: Delacroix, Manet, Courbet, Degas, Cezanne etc.

Picasso, "Still life with Bottle of Rum", 1911

Picasso,"Man with Clarinet", 1911

Picasso, "Man with Guitar", 1911

Picasso, "The Poet", 1911

But in the work of another great artist in Paris, the Spaniard Pablo Picasso, there is never any suspicion of this conventional beauty. Tossed hither and thither by the need for self-expression, Picasso hurries from one manner to another. At times a great gulf appears between consecutive manners, because Picasso leaps boldly and is found continually by his bewildered crowd of followers standing at a point very different from that at which they saw him last. No sooner do they think that they have reached him again than he has changed once more. In this way there arose Cubism, the latest of the French movements, which is treated in detail in Part II. Picasso is trying to arrive at constructiveness by way of proportion. In his latest works (1911) he has achieved the logical destruction of matter, not, however, by dissolution but rather by a kind of a parcelling out of its various divisions and a constructive scattering of these divisions about the canvas. But he seems in this most recent work distinctly desirous of keeping an appearance of matter. He shrinks from no innovation, and if colour seems likely to balk him in his search for a pure artistic form, he throws it overboard and paints a picture in brown and white; and the problem of purely artistic form is the real problem of his life.

Apparently the frequent use of geometric shapes makes these pieces spiritual - but that's not a word that I would apply to anything that Picasso did.

In their pursuit of the same supreme end Matisse and Picasso stand side by side, Matisse representing colour and Picasso form.

I have no idea what that "same supreme end" might be - other than that "inward and artistic harmony" that might also be attributed to the best artists of any time or place.

***************************

IV. THE PYRAMID

This brief section reiterates the theme of the pyramid reaching from earth to heaven, restating it a convergence of the arts:

Despite, or perhaps thanks to, the differences between them, there has never been a time when the arts approached each other more nearly than they do today, in this later phase of spiritual development.

Didn't the literature, painting, and music of the Romantic era show that same convergence?

A painter, who finds no satisfaction in mere representation, however artistic, in his longing to express his inner life, cannot but envy the ease with which music, the most non-material of the arts today, achieves this end. He naturally seeks to apply the methods of music to his own art. And from this results that modern desire for rhythm in painting, for mathematical, abstract construction, for repeated notes of colour, for setting colour in motion.

This painter is Kandinsky himself - and this is his contribution to the history of European art - arguably no less significant than Giotto's introduction of theatrical, voluminous figures.

I acknowledge the long tradition that established a hierarchy of heaven over earth - with only a single prophet reaching up to heaven and the rest of us lesser souls more or less earthbound.

But with his interest in science, Kandinsky might have noted that it's only a metaphor. There is nothing more spiritual about a cloud than about the hills beneath them. And it's a metaphor than can cut both ways -- i.e. it's better to be "grounded" than to be an "airhead".

And just because a person has been acknowledged as a prophet, it doesn't mean that he (or occasionally she) is significantly wiser, smarter, or more spiritual than many of his contemporaries with big, active brains.

This is one aspect of traditional European/Middle-Eastern thinking that Kandinsky could well have discarded.

*****************************

PART II -ABOUT PAINTING

V. THE PSYCHOLOGICAL WORKING OF COLOR

This brief section reaches the following conclusion:

IT IS EVIDENT THEREFORE THAT COLOUR HARMONY MUST REST ONLY ON A CORRESPONDING VIBRATION IN THE HUMAN SOUL; AND THIS IS ONE OF THE GUIDING PRINCIPLES OF THE INNER NEED.

He didn't really present arguments in support of it, or examine the theories of color that are closer to physics than psychology.

Nor does he consider the possibility that a general theory of color harmony is not possible at all, since they behave differently in the exact tones, hues, intensities, shapes, and dimensions as they occur within each separate painting.

VI. THE LANGUAGE OF FORM AND COLOR

Painting has two weapons at her disposal:

1. Color.

2. Form.

Kandinsky tells us that color can never occur without form -- it always has a boundary from which its effects cannot be independent. (which is why, as I suggested above, a general theory of color harmony must be problematic)

But considering the effects of the various qualities of gray, one might also suggest that form can never occur without color.

A Medieval Samurai had two weapons at his disposal: the Katana (long sword) and the Wakizashi (short sword) -- and he could use the one, the other, or both at the same time. But the same could not be said about form and color.

Form, in the narrow sense, is nothing but the separating line between surfaces of colour. That is its outer meaning. But it has also an inner meaning, of varying intensity

But can that inner meaning ever be independent of colors that it separates ?

SO IT IS EVIDENT THAT FORM-HARMONY MUST REST ONLY ON A CORRESPONDING VIBRATION OF THE HUMAN SOUL; AND THIS IS A SECOND GUIDING PRINCIPLE OF THE INNER NEED.

Again, Kandinsky has not supported his conclusion - but then, what other foundations are there that cannot, eventually, be attributed to a "vibration of the human soul" ?

Purely abstract forms are beyond the reach of the artist at present; they are too indefinite for him. To limit himself to the purely indefinite would be to rob himself of possibilities, to exclude the human element and therefore to weaken his power of expression.

Kandinsky, untitled 1910

Kandinsky himself, at the age of 44. had just begun to paint his first pure abstractions. It was probably a struggle for him to get there.

Kandinsky, "Painting with Green Center", 1913

The above piece is from the Jerome Eddy collection at the Art Institute. I like it much more than the other three Kandinsky paintings from that period, both of which still have representational imagery.

On the other hand, there exists equally no purely material form. A material object cannot be absolutely reproduced. For good or evil, the artist has eyes and hands, which are perhaps more artistic than his intentions and refuse to aim at photography alone.

Yes -and an artist also has a mind/soul, from which the hands and eyes have yet to operate independently.

Concerning photography, I don't know whether Kandinsky ever discussed this practice that was emerging as a modern art form concurrently with abstract painting.

Many genuine artists, who cannot be content with a mere inventory of material objects, seek to express the objects by what was once called "idealization," then "selection,"

But "idealization" and "selection" are unavoidable -- it's just that artists do them quite differently. Some even want things to appear cluttered and detail-heavy - with a total effect that I find repulsive. But obviously, others do not.

The impossibility and, in art, the uselessness of attempting to copy an object exactly, the desire to give the object full expression, are the impulses which drive the artist away from "literal" colouring to purely artistic aims. And that brings us to the question of composition.

Anthony Adcock, "Models", 2013

(oil on aluminum)

Here's an artist who copies things so exactly, they are nearly impossible to distinguish from the originals. And yet, even here "idealization" and "selection" could not be completely avoided.

Pure artistic composition has two elements:

1. The composition of the whole picture.

2. The creation of the various forms which, by standing in different relationships to each other, decide the composition of the whole. [Footnote: The general composition will naturally include many little compositions which may be antagonistic to each other, though helping—perhaps by their very antagonism—the harmony of the whole. These little compositions have themselves subdivisions of varied inner meanings.] Many objects have to be considered in the light of the whole, and so ordered as to suit this whole. Singly they will have little meaning, being of importance only in so far as they help the general effect. These single objects must be fashioned in one way only; and this, not because their own inner meaning demands that particular fashioning, but entirely because they have to serve as building material for the whole composition.

Cezanne, "Bathing Women", 1898-1905

[Footnote: A good example is Cezanne's "Bathing Women," which is built in the form of a triangle. Such building is an old principle, which was being abandoned only because academic usage had made it lifeless. But Cezanne has given it new life. He does not use it to harmonize his groups, but for purely artistic purposes. He distorts the human figure with perfect justification. Not only must the whole figure follow the lines of the triangle, but each limb must grow narrower from bottom to top.

The above painting strikes me a disaster, both in whole and in part. But maybe I'll feel differently the next time I see the actual piece.

Raphael's "Holy Family" is an example of triangular composition used only for the harmonizing of the group, and without any mystical motive.

[Footnote: A good example is Cezanne's "Bathing Women," which is built in the form of a triangle. Such building is an old principle, which was being abandoned only because academic usage had made it lifeless. But Cezanne has given it new life. He does not use it to harmonize his groups, but for purely artistic purposes. He distorts the human figure with perfect justification. Not only must the whole figure follow the lines of the triangle, but each limb must grow narrower from bottom to top.

The above painting strikes me a disaster, both in whole and in part. But maybe I'll feel differently the next time I see the actual piece.

Raphael, "Canigliani Holy Family", 1507

Raphael's "Holy Family" is an example of triangular composition used only for the harmonizing of the group, and without any mystical motive.

Perhaps Kandinsky would have felt differently if the putti in the corners were still present (they had been covered up during his lifetime). But either way - the triangle in this piece seems to reflect a "mystical motive" to me - while Cezanne's triangle just feels like a failed experiment.

So the abstract idea is creeping into art, although, only yesterday, it was scorned and obscured by purely material ideals. Its gradual advance is natural enough, for in proportion as the organic form falls into the background, the abstract ideal achieves greater prominence.

In the above duality, abstract = geometric. Today, 'bio-form' and 'geo-form' denote two different kinds of abstract painting.

But the organic form possesses all the same an inner harmony of its own, which may be either the same as that of its abstract parallel (thus producing a simple combination of the two elements) or totally different (in which case the combination may be unavoidably discordant). However diminished in importance the organic form may be, its inner note will always be heard; and for this reason the choice of material objects is an important one. The spiritual accord of the organic with the abstract element may strengthen the appeal of the latter (as much by contrast as by similarity) or may destroy it.

That's exactly how I feel about Cezanne's "Bathers" - the figures and the triangle have destroyed the appeal of both.

Suppose a rhomboidal composition, made up of a number of human figures. The artist asks himself: Are these human figures an absolute necessity to the composition, or should they be replaced by other forms, and that without affecting the fundamental harmony of the whole? If the answer is "Yes," we have a case in which the material appeal directly weakens the abstract appeal. The human form must either be replaced by another object which, whether by similarity or contrast, will strengthen the abstract appeal, or must remain a purely non-material symbol

I'm guessing that Kandinsky had been asking himself this question many times over the previous two years - and he was about to drop the human figure completely - with more successful results.

The Pompidou Center Kandinsky collection is currently in Milwaukee, where I got to see Kandinsky's early landscapes and figurative compositions. He had a wonderful feeling for landscape - but his figures feel like cheap book illustrations.

The more abstract is form, the more clear and direct is its appeal. In any composition the material side may be more or less omitted in proportion as the forms used are more or less material, and for them substituted pure abstractions, or largely dematerialized objects. The more an artist uses these abstracted forms, the deeper and more confidently will he advance into the kingdom of the abstract. And after him will follow the gazer at his pictures, who also will have gradually acquired a greater familiarity with the language of that kingdom.

By no coincidence, the "kingdom of forms" recalls the "kingdom of Heaven" from the Gospels

Must we then abandon utterly all material objects and paint solely in abstractions? The problem of harmonizing the appeal of the material and the non-material shows us the answer to this question. As every word spoken rouses an inner vibration, so likewise does every object represented. To deprive oneself of this possibility is to limit one's powers of expression. That is at any rate the case at present. But besides this answer to the question, there is another, and one which art can always employ to any question beginning with "must": There is no "must" in art, because art is free.

Again, we find Kandinsky struggling with this issue. Thanks, in part, to his pioneering efforts, 'non-material' art would become an acceptable high-art practice. But many artists, viewers, and collectors would still prefer see images of people and the world they live in.

It drives him to the escape hatch: "art is free". This allows everyone to do whatever they want -- but it also suggests that nothing is really any better than anything else. In the Almanac, Kandinsky chided critics for keeping the public away from new art, as if all of it were worth seeing.

It's unfortunate that his foundational documents of abstract art are so hesitant to judge it.

With regard to the second problem of composition, the creation of the single elements which are to compose the whole, it must be remembered that the same form in the same circumstances will always have the same inner appeal. Only the circumstances are constantly varying. It results that: (1) The ideal harmony alters according to the relation to other forms of the form which causes it. (2) Even in similar relationship a slight approach to or withdrawal from other forms may affect the harmony. [Footnote: This is what is meant by "an appeal of motion." For example, the appeal of an upright triangle is more steadfast and quiet than that of one set obliquely on its side.] Nothing is absolute. Form-composition rests on a relative basis, depending on (1) the alterations in the mutual relations of forms one to another, (2) alterations in each individual form, down to the very smallest. Every form is as sensitive as a puff of smoke, the slightest breath will alter it completely. This extreme mobility makes it easier to obtain similar harmonies from the use of different forms, than from a repetition of the same one; though of course an exact replica of a spiritual harmony can never be produced. So long as we are susceptible only to the appeal of a whole composition, this fact is of mainly theoretical importance. But when we become more sensitive by a constant use of abstract forms (which have no material interpretation) it will become of great practical significance. And so as art becomes more difficult, its wealth of expression in form becomes greater and greater. At the same time the question of distortion in drawing falls out and is replaced by the question how far the inner appeal of the particular form is veiled or given full expression.

I've put the final sentence in bold type because it comes as close as Kandinsky will come to offering some way to critique abstract art -- just as 'distortion' might have been used to critique the drawing of the human form.

But it doesn't go very far -- just as 'distortion' is an idea that is best abandoned outside the Figure Drawing 101 classroom.

Without such development as this, form-composition is impossible. To anyone who cannot experience the inner appeal of form (whether material or abstract) such composition can never be other than meaningless. Apparently aimless alterations in form-arrangement will make art seem merely a game. So once more we are faced with the same principle, which is to set art free, the principle of the inner need.

Or, one might say that the "apparently aimless alterations in form-arrangement" will replace Modernism with Post-Modernism. It is difficult to apply 'the principle of the inner need' when the most demanding inner needs usually involve an outer need for food, sex, money, social status, etc.

When features or limbs for artistic reasons are changed or distorted, men reject the artistic problem and fall back on the secondary question of anatomy. But, on our argument, this secondary consideration does not appear, only the real, artistic question remaining. These apparently irresponsible, but really well-reasoned alterations in form provide one of the storehouses of artistic possibilities.

Thomas Lawrence, portrait of Mrs. Jens Wolff, 1803-1815

Here's one of my favorite paintings at the Art Institute of Chicago - and apparently it was found acceptable, if not rapturously beautiful, by Mrs. Wolff and subsequent collectors.

But Mrs. Wolff's right breast appears to sprout from her collar bone - an anatomical distortion that still bothers some people, while it is ignored by others.

Not every lover and practitioner of figurative art makes judgments based upon anatomical accuracy.

.

The inner need is built up of three mystical elements: (1) Every artist, as a creator, has something in him which calls for expression (this is the element of personality). (2) Every artist, as child of his age, is impelled to express the spirit of his age (this is the element of style)—dictated by the period and particular country to which the artist belongs (it is doubtful how long the latter distinction will continue to exist). (3) Every artist, as a servant of art, has to help the cause of art (this is the element of pure artistry, which is constant in all ages and among all nationalities).

His notion of "inner need" is so important to Kandinsky - yet it becomes ever more incomprehensible to me as it needs "to express the spirit of his age" and "help the cause of art". Both of those seem to be firmly located outside the artist.

Only the third element—that of pure artistry—will remain for ever. An Egyptian carving speaks to us today more subtly than it did to its chronological contemporaries; for they judged it with the hampering knowledge of period and personality. But we can judge purely as an expression of the eternal artistry.

Similarly—the greater the part played in a modern work of art by the two elements of style and personality, the better will it be appreciated by people today; but a modern work of art which is full of the third element, will fail to reach the contemporary soul. For many centuries have to pass away before the third element can be received with understanding. But the artist in whose work this third element predominates is the really great artist.

Tomb of Kagemni, 6th Dynasty (Old Kingdom)

This reminds me of an exchange of emails I had with a former director of the Art Institute of Chicago. I asked him why the museum continued to categorically exclude even the very best examples of contemporary Impressionism or other traditional European practices - and he replied that they were not the art of our time.

Too bad I didn't know enough to share the above quotation about "pure artistry" with him - though I fear that it somewhat contradicts Kandinsky's own notion of the ever-rising pyramid of human spirituality - as well as his antipathy towards material (i.e. realistic) art.

Speaking of pyramids - the 2500 year practice of Egyptian art would seem to qualify as "pure artistry" - especially as it did not change in response to the personalities of the artists or the surrounding society.

In this respect, Kandinsky was radically conservative.

.. as style and personality create in every epoch certain definite forms, which, for all their superficial differences, are really closely related, these forms can be spoken of as one side of art—the SUBJECTIVE. Every artist chooses, from the forms which reflect his own time, those which are sympathetic to him, and expresses himself through them. So the subjective element is the definite and external expression of the inner, objective element.

The inevitable desire for outward expression of the OBJECTIVE element is the impulse here defined as the "inner need." The forms it borrows change from day to day, and, as it continually advances, what is today a phrase of inner harmony becomes tomorrow one of outer harmony. It is clear, therefore, that the inner spirit of art only uses the outer form of any particular period as a stepping-stone to further expression.

In short, the working of the inner need and the development of art is an ever-advancing expression of the eternal and objective in the terms of the periodic and subjective.

Because the objective is forever exchanging the subjective expression of today for that of tomorrow, each new extension of liberty in the use of outer form is hailed as the last and supreme. At present we say that an artist can use any form he wishes, so long as he remains in touch with nature. But this limitation, like all its predecessors, is only temporary. From the point of view of the inner need, no limitation must be made. The artist may use any form which his expression demands; for his inner impulse must find suitable outward expression.

So we see that a deliberate search for personality and "style" is not only impossible, but comparatively unimportant. The close relationship of art throughout the ages, is not a relationship in outward form but in inner meaning. And therefore the talk of schools, of lines of "development," of "principles of art," etc., is based on misunderstanding and can only lead to confusion.

A nice inversion of the usual application of "subjective" and "objective" in art talk - though this "objective element" may be one that nobody but him can identify.

And I like his attack on "talk of schools...lines of development..and principles of art" --- but all talk about art is problematic.

All means are sacred which are called for by the inner need. All means are sinful which obscure that inner need....It is impossible to theorize about this ideal of art. In real art theory does not precede practice, but follows her. Everything is, at first, a matter of feeling. Any theoretical scheme will be lacking in the essential of creation—the inner desire for expression—which cannot be determined. Neither the quality of the inner need, nor its subjective form, can be measured nor weighed.

This would seem contrary to art practices that begin with an idea and then look for appropriate forms. So Kandinsky would probably not consider conceptual art to be "real art"

The inner need is the basis alike of small and great problems in painting. We are seeking today for the road which is to lead us away from the outer to the inner basis.

[Footnote: The term "outer," here used, must not be confused with the term "material" used previously. I am using the former to mean "outer need," which never goes beyond conventional limits, nor produces other than conventional beauty. The "inner need" knows no such limits, and often produces results conventionally considered "ugly." But "ugly" itself is a conventional term, and only means "spiritually unsympathetic," being applied to some expression of an inner need, either outgrown or not yet attained. But everything which adequately expresses the inner need is beautiful.]

And yet -- what was more conventional than those 2500 years of Egyptian art - or the even longer tradition of Australian Dreamtime art ? If conventions can be so successfully internalized that they express an inner need, why not make that attempt ?

I'll agree that "ugly" means "spiritually unsympathetic", but that lack of sympathy may or may not be conventional.

And I doubt that the adequate expression of everyone's inner need- without exception - would appear beautiful to either me or Kandinsky --- unless we allow for an "inner need" of which the person may never be aware.

The spirit, like the body, can be strengthened and developed by frequent exercise. Just as the body, if neglected, grows weaker and finally impotent, so the spirit perishes if untended. And for this reason it is necessary for the artist to know the starting point for the exercise of his spirit.

The starting point is the study of colour and its effects on men.

We are first asked to compare yellow with blue - noting that "the warm colors approaching the spectator, the cold ones retreating from him."

We are also to notice that:

"in the yellow a spreading movement out from the centre, and a noticeable approach to the spectator. The blue, on the other hand, moves in upon itself, like a snail retreating into its shell, and draws away from the spectator"

I don't especially feel that wherever yellow and blue are found -- but I also don't always feel the following characterizations of various colors - even as colored circles against a white ground:

*Just as orange is red brought nearer to humanity by yellow, so violet is red withdrawn from humanity by blue. But the red in violet must be cold, for the spiritual need does not allow of a mixture of warm red with cold blue.

*Violet is rather sad and ailing. It is worn by old women.

*Orange is like a man, convinced of his own powers

*Green is the most restful colour that exists. On exhausted men this restfulness has a beneficial effect, but after a time it becomes wearisome.

*Yellow is the typically earthly colour. It can never have profound meaning.

Experiencing these effects while staring at various colors is presented as an exercise to strengthen the spirit, but it seems more like a psychology than a spirituality of color. And I wonder whether Kandinsky actually practiced it as a daily spiritual calisthenic distinct from the making of paintings..

Delacroix, "Hercules and Alcestis", 1862 (detail)

" Gray = immobility and rest. Delacroix sought to express rest by a mixture of green and red"

Mark Rothko , 1968

Here's a painting that seems to exemplify the above contemplations about solid areas of color - and the word "spiritual" is often applied to Rotho's work from this period.

Kandinsky, "Painting with Red Spot", 1914

Kandinsky's own work seems better characterized by the following:

The strife of colours, the sense of balance we have lost, tottering principles, unexpected assaults, great questions, apparently useless striving, storm and tempest, broken chains, antitheses and contradictions, these make up our harmony. The composition arising from this harmony is a mingling of colour and form each with its separate existence, but each blended into a common life which is called a picture by the force of the inner need

Raphael, 1505

Harmony today rests chiefly on the principle of contrast which has for all time been one of the most important principles of art. But our contrast is an inner contrast which stands alone and rejects the help (for that help would mean destruction) of any other principles of harmony.......It is interesting to note that this very placing together of red and blue was so beloved by the primitive both in Germany and Italy that it has till today survived, principally in folk pictures of religious subjects. One often sees in such pictures the Virgin in a red gown and a blue cloak. It seems that the artists wished to express the grace of heaven in terms of humanity, and humanity in terms of heaven

Leonardo Da Vinci, "Madonna Litta", 1490

I've pulled up a few "non-primitive" examples of the Virgin in a red blouse and blue cape.

That combination does seem appropriate for a person who exemplifies the union of heaven and earth, spirit and flesh.

Le Fauconnier, "Abundance" , 1910 (detail)

Compare the article by Le Fauconnier in the catalogue of the second exhibition of the Neue Kunstlervereinigung, Munich, 1910-11. There has arisen out of the composition in flat triangles a composition with plastic three-dimensional triangles, that is to say with pyramids; and that is Cubism. But there has arisen here also the tendency to inertia, to a concentration on this form for its own sake, and consequently once more to an impoverishment of possibility. But that is the unavoidable result of the external application of an inner principle.

I don't know whether the above text refers to this painting - but in the reproduction, there is an unpleasant feeling that might be attributed to "a tendency to inertia". Cubism made it au courant, but does not redeem it from boredom.

A further point of great importance must not be forgotten. There are other means of using the material plane as a space of three dimensions in order to create an ideal plane. The thinness or thickness of a line, the placing of the form on the surface, the overlaying of one form on another may be quoted as examples of artistic means that may be employed. Similar possibilities are offered by colour which, when rightly used, can advance or retreat, and can make of the picture a living thing, and so achieve an artistic expansion of space. The combination of both means of extension in harmony or concord is one of the richest and most powerful elements in purely artistic composition.

The above emphasizes the use of color to "advance or retreat" within an "artistic expansion of space".

And that does seem to be Kandinsky's primary interest as a painter.

*********************

VII. THEORY

Persian "Polonaise" carpet, 17th C. (Detail)

If we begin at once to break the bonds which bind us to nature, and devote ourselves purely to combination of pure colour and abstract form, we shall produce works which are mere decoration, which are suited to neckties or carpets. Beauty of Form and Colour is no sufficient aim by itself, despite the assertions of pure aesthetes or even of naturalists, who are obsessed with the idea of "beauty." It is because of the elementary stage reached by our painting that we are so little able to grasp the inner harmony of true colour and form composition. The nerve vibrations are there, certainly, but they get no further than the nerves, because the corresponding vibrations of the spirit which they call forth are too weak. When we remember, however, that spiritual experience is quickening, that positive science, the firmest basis of human thought, is tottering, that dissolution of matter is imminent, we have reason to hope that the hour of pure composition is not far away.

"Merely decorative" should probably be translated as "not very decorative at all"

Does the above carpet produce "vibrations in the spirit" that are too weak ?

I wouldn't say that -- but then confess that when 16th C. Persian narrative miniature painting shares a gallery with carpets (as it does in the Met), I spend 95% of my time looking at the narrative paintings.

BTW -- exactly a hundred years later, despite the dissolution of matter, positive science still seems to be going strong, while the quickening of "spiritual experience" seems limited to pockets of like-minded enthusiasts.

Turkish carpet, late 18th, early 19th c.

It must not be thought that pure decoration is lifeless. It has its inner being, but one which is either incomprehensible to us, as in the case of old decorative art, or which seems mere illogical confusion, as a world in which full-grown men and embryos play equal roles, in which beings deprived of limbs are on a level with noses and toes which live isolated and of their own vitality. The confusion is like that of a kaleidoscope, which though possessing a life of its own, belongs to another sphere. Nevertheless, decoration has its effect on us; oriental decoration quite differently to Swedish, savage, or ancient Greek. It is not for nothing that there is a general custom of describing samples of decoration as gay, serious, sad, etc., as music is described as Allegro, Serioso, etc., according to the nature of the piece.

Turkish (Iznik) tile, 1578

Kandinsky seems to have been sensitive to the criticism that abstract art was "mere decoration" (a charge still leveled by the devotees of Ayn Rand) -- so he wanted to make it perfectly clear that he recognized a very important difference: decorative art was about the nerve endings (sensual), while abstract art was spiritual.

Hence, the topic of this essay, even though Kandinsky's notion of "spiritual" does not seem to be distinguishable from psychological.

Probably conventional decoration had its beginnings in nature. But when we would assert that external nature is the sole source of all art, we must remember that, in patterning, natural objects are used as symbols, almost as though they were mere hieroglyphics. For this reason we cannot gauge their inner harmony. For instance, we can bear a design of Chinese dragons in our dining or bed rooms, and are no more disturbed by it than by a design of daisies.

18th-19C Myochin family (Japanese armorers)

I don't see why "inner harmony" cannot be gauged regardless of whether the dragon is found in a chair, on a pot, or free standing.

Han Dynasty tomb sculpture

How I wish a major museum would curate an exhibit on this subject matter.

Celine Lepage (1882-1928)

It is possible that towards the close of our already dying epoch a new decorative art will develop, but it is not likely to be founded on geometrical form. At the present time any attempt to define this new art would be as useless as pulling a small bud open so as to make a fully blown flower. Nowadays we are still bound to external nature and must find our means of expression in her. But how are we to do it? In other words, how far may we go in altering the forms and colours of this nature?

Art Deco was the new style of decorative art that followed in the coming decades - and mostly it incorporated natural forms. Then came the less naturalistic forms of the Bauhaus -- of which Kandinsky himself would himself become a faculty member until it closed.

Rogier Van Der Weyden, "Deposition" , 1435 (detail)

A warm red tone will materially alter in inner value when it is no longer considered as an isolated colour, as something abstract, but is applied as an element of some other object, and combined with natural form. The variety of natural forms will create a variety of spiritual values, all of which will harmonize with that of the original isolated red......A red sky suggests to us sunset, or fire, and has a consequent effect upon us—either of splendour or menace. Much depends now on the way in which other objects are treated in connection with this red sky.....A red garment is quite a different matter; for it can in reality be of any colour. Red will, however, be found best to supply the needs of pure artistry, for here alone can it be used without any association with material aims. The artist has to consider not only the value of the red cloak by itself, but also its value in connection with the figure wearing it, and further the relation of the figure to the whole picture. Suppose the picture to be a sad one, and the red-cloaked figure to be the central point on which the sadness is concentrated—either from its central position, or features, attitude, colour, or what not. The red will provide an acute discord of feeling, which will emphasize the gloom of the picture. The use of a colour, in itself sad, would weaken the effect of the dramatic whole.

The above "Descent from the Cross" seems to exemplify the use of a red garment to accentuate sadness - and to exemplify "the principle of antithesis" -- using discord to achieve harmony.

Perhaps it also accentuates sadness in this Nativity by the workshop of the same artist ?

Or maybe it's the only note of joy in an otherwise muted celebration ?

As Kandinsky notes " Rules cannot be laid down, the variations are so endless. A single line can alter the whole composition of a picture."

The spectator is too ready to look for a meaning in a picture—i.e., some outward connection between its various parts. Our materialistic age has produced a type of spectator or "connoisseur," who is not content to put himself opposite a picture and let it say its own message. Instead of allowing the inner value of the picture to work, he worries himself in looking for "closeness to nature," or "temperament," or "handling," or "tonality," or "perspective," or what not. His eye does not probe the outer expression to arrive at the inner meaning. In a conversation with an interesting person, we endeavour to get at his fundamental ideas and feelings. We do not bother about the words he uses, nor the spelling of those words, nor the breath necessary for speaking them, nor the movements of his tongue and lips, nor the psychological working on our brain, nor the physical sound in our ear, nor the physiological effect on our nerves. We realize that these things, though interesting and important, are not the main things of the moment, but that the meaning and idea is what concerns us. We should have the same feeling when confronted with a work of art. When this becomes general the artist will be able to dispense with natural form and colour and speak in purely artistic language.

I like the metaphor of "a conversation with an interesting person" ---and the search for the "main thing of the moment"

Although -- that's a search that privileges the novelty of personality. The artist is more important than the art.

And Kandinsky seems to be just as ready to dismiss the naturalistic as the materialistic spectator is to dismiss its absence.

In dance as in painting this is only a stage of transition. In dancing as in painting we are on the threshold of the art of the future. The same rules must be applied in both cases. Conventional beauty must go by the board and the literary element of "story-telling" or "anecdote" must be abandoned as useless. Both arts must learn from music that every harmony and every discord which springs from the inner spirit is beautiful, but that it is essential that they should spring from the inner spirit and from that alone.

Dr. Kevorkian

This is at least the third time Kandinsky has asserted that any expression of the inner spirit is beautiful, so I'm wondering whether he might have allowed for any exceptions.

His injunction against story-telling seems to have become a dogma in the contemporary artworld, since not very many A-list artists have gotten there by telling stories in the last 60 years.

He then carries it over to ballet - suggesting that the dance of the future will be less about "external motives—the expression of love and fear, etc"

(at this point, the editor of this translation intercedes to question whether Isadore Duncan was a good correlative of modernist painters who were seeking inspiration from the primatives. Kandinsky identifies her as such - but that might just suggest that his notion of 'primitive' is not synonymous with non-Classical)

From what has been said of the combination of colour and form, the way to the new art can be traced. This way lies today between two dangers. On the one hand is the totally arbitrary application of colour to geometrical form—pure patterning. On the other hand is the more naturalistic use of colour in bodily form—pure phantasy. Either of these alternatives may in their turn be exaggerated. Everything is at the artist's disposal, and the freedom of today has at once its dangers and its possibilities. We may be present at the conception of a new great epoch, or we may see the opportunity squandered in aimless extravagance.

I wonder where Kandinsky found "aimless extravagance" among the painters of his time - just as I wonder whether someone's "inner need" might drive that extravagance. He likes to strike a righteous, moral posture -- but will not even give examples, much less explanations.

That art is above nature is no new discovery. [Footnote: Cf. "Goethe", by Karl Heinemann, 1899, p. 684; also Oscar Wilde, "De Profundis"; also Delacroix, "My Diary".] New principles do not fall from heaven, but are logically if indirectly connected with past and future. What is important to us is the momentary position of the principle and how best it can be used. It must not be employed forcibly. But if the artist tunes his soul to this note, the sound will ring in his work of itself. The "emancipation" of today must advance on the lines of the inner need. It is hampered at present by external form, and as that is thrown aside, there arises as the aim of composition-construction. The search for constructive form has produced Cubism, in which natural form is often forcibly subjected to geometrical construction, a process which tends to hamper the abstract by the concrete and spoil the concrete by the abstract.

I assume he's mostly referring to analytic cubism which had a short run, possibly for the reasons Kandinsky has just given. Though I don't understand how "spoiling the concrete" would be unwelcome by him.

The harmony of the new art demands a more subtle construction than this, something that appeals less to the eye and more to the soul. This "concealed construction" may arise from an apparently fortuitous selection of forms on the canvas. Their external lack of cohesion is their internal harmony. This haphazard arrangement of forms may be the future of artistic harmony. Their fundamental relationship will finally be able to be expressed in mathematical form, but in terms irregular rather than regular

These concluding words would seem to prefigure Kandinsky's next book, where the subject is "points, lines, and planes" rather than spirituality.

***************************************

VIII. ART AND ARTISTS

**************************************

The work of art is born of the artist in a mysterious and secret way. From him it gains life and being. Nor is its existence casual and inconsequent, but it has a definite and purposeful strength, alike in its material and spiritual life. It exists and has power to create spiritual atmosphere; and from this inner standpoint one judges whether it is a good work of art or a bad one. If its "form" is bad it means that the form is too feeble in meaning to call forth corresponding vibrations of the soul.

Unfortunately, Kandinsky is not going to elaborate on "vibrations of the soul". What else makes the soul vibrate? How can one determine when it is happening ?

But at least he does offer the following examples by way of contrast:

Balthasar Denner (1685-1749)

Canaletto (1697-1768)

Note, however, that blind following of scientific precept is less blameworthy than its blind and purposeless rejection. The former produces at least an imitation of material objects which may be of some use.

[Footnote: Plainly, an imitation of nature, if made by the hand of an artist, is not a pure reproduction. The voice of the soul will in some degree at least make itself heard. As contrasts one may quote a landscape of Canaletto and those sadly famous heads by Denner.—(Alte Pinakothek, Munich.)]

The latter is an artistic betrayal and brings confusion in its train. The former leaves the spiritual atmosphere empty; the latter poisons it.

It's difficult for me to feel the "spiritual atmosphere" of Canaletto as "empty" -- but then I also don't feel that the atmosphere of the Denner portrait has been "poisoned" . (though I've never seen an actual piece - he's not even in the Met)

I wonder whether Kandinsky experienced positive spiritual vibrations from any painting made for the Age of Enlightenment.

Painting is an art, and art is not vague production, transitory and isolated, but a power which must be directed to the improvement and refinement of the human soul—to, in fact, the raising of the spiritual triangle.

If art refrains from doing this work, a chasm remains unbridged, for no other power can take the place of art in this activity. And at times when the human soul is gaining greater strength, art will also grow in power, for the two are inextricably connected and complementary one to the other. Conversely, at those times when the soul tends to be choked by material disbelief, art

This declaration contrasts quite strongly with "Painting is therapy, a sort of escapism for me personally. This feeling allows me to enter a world that only I have access to; I can be alone with my thoughts and ideas" --- pulled from this compilation of contemporary Chicago artists responding to the question "What is painting?".(it's an ongoing project; the first four responses were similarly self centered)

Then is the bond between art and the soul, as it were, drugged into unconsciousness. The artist and the spectator drift apart, till finally the latter turns his back on the former or regards him as a juggler whose skill and dexterity are worthy of applause. It is very important for the artist to gauge his position aright, to realize that he has a duty to his art and to himself, that he is not king of the castle but rather a servant of a nobler purpose. He must search deeply into his own soul, develop and tend it, so that his art has something to clothe, and does not remain a glove without a hand.

I'm not sure that even Kandinsky could keep this "noble purpose" in sight.

My father once shared similar ideals, as once articulated by his mentor, Milton Horn (1906-1995) in 1948: "The function of sculpture is not to decorate but to integrate, not to entertain but to orientate man within the context of his universe."

But twenty later, my father succinctly stated that sculpture, for him, was an opportunity to demonstrate a rare and difficult skill - much as an acrobat might do.

THE ARTIST MUST HAVE SOMETHING TO SAY, FOR MASTERY OVER FORM IS NOT HIS GOAL BUT RATHER THE ADAPTING OF FORM TO ITS INNER MEANING.

[Footnote: Naturally this does not mean that the artist is to instill forcibly into his work some deliberate meaning. As has been said the generation of a work of art is a mystery. So long as artistry exists there is no need of theory or logic to direct the painter's action. The inner voice of the soul tells him what form he needs, whether inside or outside nature. Every artist knows, who works with feeling, how suddenly the right form flashes upon him. Bocklin said that a true work of art must be like an inspiration; that actual painting, composition, etc., are not the steps by which the artist reaches self-expression

But note that Kandinsky will not suggest how, or even if, that inner voice of the soul is to be evaluated. Where might such a discussion begin?

Arnold Bocklin, Isle of the Dead

Something like the above image was probably in Bocklin's imagination before he painted it.

Kandinsky, Impression V,1911

But what could have been in Kandinsky's mind when he began painting this one ?

The artist has a triple responsibility to the non-artists: (1) He must repay the talent which he has; (2) his deeds, feelings, and thoughts, as those of every man, create a spiritual atmosphere which is either pure or poisonous. (3) These deeds and thoughts are materials for his creations, which themselves exercise influence on the spiritual atmosphere. The artist is not only a king, as Peladan says, because he has great power, but also because he has great duties.

This was my introduction to Josephin Peladan - whose discussion of spirituality and art was a bit more explicit: "The Beauty of the Father is called Intensity. The Beauty of the Son is called Subtlety. The Beauty of the Holy Spirit is called Harmony."

Peladan may have shared Kandinsky's moral duality of "pure" and "poisonous". It seems characteristic of Christian (as well as Muslim) thought.

If the artist be priest of beauty, nevertheless this beauty is to be sought only according to the principle of the inner need, and can be measured only according to the size and intensity of that need.

THAT IS BEAUTIFUL WHICH IS PRODUCED BY THE INNER NEED, WHICH SPRINGS FROM THE SOUL.

Are size and intensity the only ways to evaluate "inner need", and therefore "beauty" ? Without something like compassion, that might advocate feelings and art that are monstrous.

*****************************

CONCLUSION

*****************************

The first five illustrations in this book show the course of constructive effort in painting. This effort falls into two divisions:

(1) Simple composition, which is regulated according to an obvious and simple form. This kind of composition I call the MELODIC.

(2) Complex composition, consisting of various forms, subjected more or less completely to a principal form. Probably the principal form may be hard to grasp outwardly, and for that reason possessed of a strong inner value. This kind of composition I call the SYMPHONIC.

These are the first five illustrations shown in this edition:

Mosaics in S. Vitale, Ravenna

Victor and Heinrich Dunwegge: "The Crucifixion" (in the Alte

Pinakothek, Munich)

Pinakothek, Munich)

(The artist of the above is now listed as "Derick Baegert")

In this crowded composition the principal figures are

about fifteen inches high, and display great variety of

action. The dresses are exceedingly picturesque, and

include many rich examples of brocade. Great indivi-

duality is noticeable in some of the heads. The men's

features are for the most part coarse in expression, but

some of the female faces realize a certain sense of

beauty. At the foot of the cross on which one of the

malefaftors is crucified, stands a woman (probably in-

tended to represent his wife) weeping. Various incidents

connected with the last scenes of the Passion—-as, for

instance, the procession to Calvary, and the Descent from

the Cross, and the death of ]udas—are introduced in the

background. In the mounted group to the right consider-

able attention has been bestowed on animal form. The foli-

age of shrubs in the middle distance is carefully detailed.

Portions of the work are excellent in quality of colour,

but the general effect can hardly be called harmonious.

Albrecht Durer: "The Descent from the Cross" (in the Alte

Pinakothek, Munich)

Pinakothek, Munich)

Raphael: "The Canigiani Holy Family"

(in the Alte Pinakothek,Munich)

Paul Cezanne: "Bathing Women"

Between the two lie various transitional forms, in which the melodic principle predominates. The history of the development is closely parallel to that of music.

If, in considering an example of melodic composition, one forgets the material aspect and probes down into the artistic reason of the whole, one finds primitive geometrical forms or an arrangement of simple lines which help toward a common motion. This common motion is echoed by various sections and may be varied by a single line or form. Such isolated variations serve different purposes. For instance, they may act as a sudden check, or to use a musical term, a "fermata."

[Footnote: E.g., the Ravenna mosaic which, in the main, forms a triangle. The upright figures lean proportionately to the triangle. The outstretched arm and door-curtain are the "fermate."] Each form which goes to make up the composition has a simple inner value, which has in its turn a melody. For this reason I call the composition melodic. By the agency of Cezanne and later of Hodler [Footnote: English readers may roughly parallel Hodler with Augustus John for purposes of the argument.—M.T.H.S.] this kind of composition won new life, and earned the name of "rhythmic." The limitations of the term "rhythmic" are obvious. In music and nature each manifestation has a rhythm of its own, so also in painting. In nature this rhythm is often not clear to us, because its purpose is not clear to us. We then speak of it as unrhythmic. So the terms rhythmic and unrhythmic are purely conventional, as also are harmony and discord, which have no actual existence. [Footnote: As an example of plain melodic construction with a plain rhythm, Cezanne's "Bathing Women" is given in this book.]

[Footnote: E.g., the Ravenna mosaic which, in the main, forms a triangle. The upright figures lean proportionately to the triangle. The outstretched arm and door-curtain are the "fermate."] Each form which goes to make up the composition has a simple inner value, which has in its turn a melody. For this reason I call the composition melodic. By the agency of Cezanne and later of Hodler [Footnote: English readers may roughly parallel Hodler with Augustus John for purposes of the argument.—M.T.H.S.] this kind of composition won new life, and earned the name of "rhythmic." The limitations of the term "rhythmic" are obvious. In music and nature each manifestation has a rhythm of its own, so also in painting. In nature this rhythm is often not clear to us, because its purpose is not clear to us. We then speak of it as unrhythmic. So the terms rhythmic and unrhythmic are purely conventional, as also are harmony and discord, which have no actual existence. [Footnote: As an example of plain melodic construction with a plain rhythm, Cezanne's "Bathing Women" is given in this book.]

Can a "rhythmic" composition be based on any shape other than a triangle ? No other kind of example was offered - though I'm not sure what the two Crucifixion designs are supposed to exemplify.

The Durer and Baegart pieces have triangles in them, but they don't seem as dominant as they are in the Raphael and Cezanne.

And I'm wondering just how far a discussion of pictorial composition can go without reference to representative and narrative features. Can the eye-mind avoid responding to them ? Should it even try?

As examples of the new symphonic composition, in which the melodic element plays a subordinate part, and that only rarely, I have added reproductions of four of my own pictures.

They represent three different sources of inspiration:

Impression No. III (concert) , 1911

(1) A direct impression of outward nature, expressed in purely artistic form. This I call an "Impression."

The 1946 edition included Impression IV (Moscow), but I could not find that one online.

Impression No. III looks quite beautiful, though.

Improvisation 28, 1912

(2) A largely unconscious, spontaneous expression of inner character, the non-material nature. This I call an "Improvisation."

Composition IV,1911

(3) An expression of a slowly formed inner feeling, which comes to utterance only after long maturing. This I call a "Composition." In this, reason, consciousness, purpose, play an overwhelming part. But of the calculation nothing appears, only the feeling. Which kind of construction, whether conscious or unconscious, really underlies my work, the patient reader will readily understand.

An interesting way to categorize his work - though it seems that he applied it less often after the war, and may have stopped doing Impressions and Improvisations entirely.

Finally, I would remark that, in my opinion, we are fast approaching the time of reasoned and conscious composition, when the painter will be proud to declare his work constructive. This will be in contrast to the claim of the Impressionists that they could explain nothing, that their art came upon them by inspiration. We have before us the age of conscious creation, and this new spirit in painting is going hand in hand with the spirit of thought towards an epoch of great spiritual leaders.

This leads right into his career as a professor at the Bauhaus, and his next book about points, lines, and planes. I'm more fond of his spontaneous work - but then, lost soul that I am, I also like paintings that mimic nature and tell stories.

******************

******************

My own conclusions

******************

******************

Kandinsky develops a notion of "the spiritual" in contrast to the perceived materialism of 19th C. realistic painting, just as the "Age of Aquarius" spirituality of the 1960's was a reaction against the perceived materialism of post-war America. But he doesn't define any goals or methods for it beyond a simple upward direction.

So it doesn't set any kind of agenda for himself or others -- beyond the avoidance of narrative and realistic imagery.

It attempts to justify purely abstract art -- in response to the then overwhelming assertion that it was merely decorative.

But that justification is so threadbare, it's hardly convincing - except for those who have already been convinced by the abstract paintings themselves. He's made no attempt to distinguish the spirituality of one abstract painting as opposed to another. So it's not surprising - at least to me - that the spiritual force in his own painting seemed to dissipate after he lost contact with the Blue Riders and became a professor at the Bauhaus.

A strong tradition of Modern, post-Christian spiritual art has yet to arise.

No comments:

Post a Comment