Rubens (1577 - 1640), Self portrait, 1623

This book is the catalog for the 1994 "Age of Rubens " exhibit at the Toledo Museum of Art.

How did I miss it ??? It certainly would have been worth the four-hour drive from Chicago.

An amazing self portrait, centered around the artist/diplomat’s penetrating eye.

Unlike Rembrandt, he was not a man for introspection.

This piece was given by the artist to the Prince of Wales (later Charles I) to atone for a commission which the artist's hand had never touched. Pity that the king had a sharper eye for art than politics..

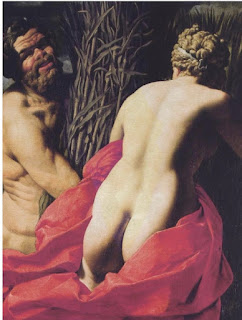

Rubens, Garden of Love, 1630-1635, detail

Selected on the premise that paintings of the highest quality are the most historically representative and eloquent, the show is comprised of works of acknowledged excellence as well as paintings whose merits may have been overlooked.......curator, Peter Sutton

This premise is the wishful thinking of an aesthete - but being one as well, it' s how I'd like all exhibitions to be assembled.

Mediocre paintings - no matter how useful they’ve been to those who commissioned or bought them - do not belong on the walls of an art museum.

BTW - it does appear that Sutton’s career in museum management peaked in the 1980’s when he was chief curator of European painting at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. His last twenty years had him leading an arts and natural history museum in Greenwich.

Curator’s Preface

The Age of Rubens traces the origins and development of the prevailing styles and themes of Flemish baroque painting, specifically as they relate to the religious and secular concerns of the era. The triumph of this art was to fashion a new form of painting that was neither a mere graft on the indigenous naturalistic tradition, which would flourish just to the north in Holland, nor a slavish adaptation of the international classicism exported from Italy, but an innovative amalgam of the two, with its own unique combination of vitality and grandeur. This new vision had a special relevance for all levels of society. Powerful incentives for baroque painting were provided by the official patronage of the Counter Reformation; altarpieces and other religious decorations were ordered in unprecedented numbers by the Church, foreign princes, and the Roman Catholic court. However, Flemish artists also worked for secular patrons - guilds, confraternities, magistrates, and wealthy burghers - as well as the open market. A great variety of new representational practices arose to fulfill devotional and other expressive needs no longer satisfied by older artistic conventions.

At its core, Flemish baroque painting also presents a famous art historical anomaly: whereas most great movements of art occur during periods of growth, Flemish seventeenth-century art flourished amidst war, foreign domination, social diaspora and relative economic stagnation. Paradoxically, while the art of Rubens and his contemporaries expressed optimism, health, sumptuous well being, intellectual curiosity and excitement, during his career his homeland saw diminished or contracting expectations and economic decline. For some critics Rubens has even seemed a false representative of the national patrimony - the lush hothouse product of an international array of elite patrons. However for other viewers his development has made him the standard-bearer of a spiritual renewal and dynamism that inspired his country until well into the nineteenth century. There can be no simple mechanistic explanation of cultural life, but a closer examination of the economic and social history of the period reveals a brief reprise from hardship just preceding and during the time of the Twelve Year Truce which brought a new national promise. A vital factor in this efflorescence was the surge in official activity patronage. The sumptuous and dignified court of the archdukes favored a few court painters, but more important was the Catholic restoration that infused all aspects of culture and daily life. The forces of the Counter Reformation transformed the Spanish Netherlands into one of the most fervently Catholic nations on earth. Religious orders multiplied and, especially under the Jesuits, infused all levels of education. While strict orthodoxy was enforced in curricula and a censorious eye cast upon expressions of free thought, intellectual life in Flanders and Brabant nonetheless remained vital. Antwerp became a major center of religious publishing and the court in Brussels a cosmopolitan refuge for persecuted Catholics. Indeed it is a testament to the national promise that in 1609 Rubens chose to remain in the country rather than return to his beloved Italy.

The official spiritual charge to Rubens and his colleagues was to fashion a new art that would at once edify, convert, and arouse ever greater religious fervor. Paradoxically, the same Church that had tried to defeat and discredit the humanists also sought to fuse the spirit and ideals of the Renaissance with their own religious and cultural imperatives. Rubens and his fellow painters responded triumphantly not only with a new Counter Reformation iconography (particularly stressing the Passion, the Immaculate Conception, and the Assumption of the Virgin, as well as the sacrament of the Eucharist and the doctrine of transubstantiation) but also a formal language that revived and vitalized classical form. The result was the most militantly religious art in Europe.

A succinct conflation of art and history.

We may note, however, that the history of art, per se (the "Life of Forms in Art"), or of European spiritual life, is not going to be addressed. Except, perhaps, obliquely. "Militant religious art" is not a positive phrase. Could it be applied to any other period of art in world history?

But in the late twentieth century Rubens and Flemish art, particularly for American audiences, is an acquired taste. Only superficially is this aversion related to modern canons of proportion - the taste for the skeletal fashions of Vogue or the angst and anorexia of Egon Schiele; after all, Rubens himself, in his unpublished treatise on antique sculpture, berated his contemporaries for neglecting physical fitness and falling short of the ancients' ideal of the classical human form. More fundamental is the skepticism and unease felt by viewers in our highly secularized, egalitarian age when presented with devout and hieratic art, spiritually informed and proselytizing painting, art at the service of organized religion and the state. Contemporary sensibilities treasure instead the private artistic statement, its idiosyncrasy and traces of individual emotion. In such a solipsistic climate, baroque art's celebration of the exterior aspect of gesture, of the shared ideals of authority, society, and faith can be misconstrued as mere grandiloquence or bombast. Yet this generous rhetorical language can speak again with a universal grandeur and eloquence. The Age of Rubens is dedicated to making this language intelligible once more, and to making Flemish baroque painting more accessible and meaningful for modern museum visitors.

Hopefully, Sutton will not be "making this language intelligible" by only explaining its iconography. If the paintings are no more than text - then their virtues can be no greater than "mere grandiloquence or bombast."

The two Rubens’ pieces he's already shown have much more than that

Now he'll set the table with brief introductions to the leading Flemish painters c. 1600

INTRODUCTION

Marten de Vos (1532-1603), Virgin and Child Welcoming the Cross, c. 1600

The leading artist at the beginning of this period was Marten de Vos who trained with Frans Floris (1519-1570), the most influential Antwerp history painter in the mid sixteenth century.

Sutton briefly discusses the religious iconography of this piece, but that does not redeem its pathetic formal quality that is almost bad enough to make it feel ironic. (BTW, the artist was a Lutheran who converted to Catholicism)

Frans Floris, Fall of the Rebellious Angels, 1554

(Not included in this exhibit)

Yikes! De Vos did not have much in common with Floris, his teacher, who regretfully was crushed by an eruption of fanatic iconoclasm that destroyed much of his life’s work. A real tragedy. The above compares well with Michelangelo’s Last Judgment, done 20 years earlier.

Hendrick de Clerck, Moses Striking the Rock, 1590

(Not in this exhibit)

Many of the monumental and colorfully decorative features of de Vos's art were taken up by his pupil Hendrick de Clerck (ca. 1560/70-1629)

the dense composition and the elaborate poses of a work like de Clerck's Moses Striking the Rock at Mara ca. 1590 make a conspicuous show of formal torsions and exaggeration that are wholly in the mannerist spirit. The subject of this painting, like other Old Testament themes which gained favor at this time, typically revives the medieval tradition of Christological prefigurations recommended by the Council of Trent; the shepherd and savior of his people, Moses was an important forerunner of Christ, and the spring that he created was regarded as a prefiguration of the sacramental waters of the Christian baptism. Old Testament prefigurations remained a prominent feature of Counter Reformation iconography, figuring for example in Rubens's decorative cycle for the ceiling of the Jesuit church in Antwerp

Ok, the Christological iconography is there if you hunt for it - but it has no connection to the visuality of this painting.

I far prefer the text posted online by the museum that owns it:

The theme is apt for a dining room. The decorative nature of the picture, in which the subject matter seems less important than the presentation of a complex and figure-filled composition, is underscored by the abundance of serving vessels, the charming variety of the participants’ poses, the forest setting and a brilliant colourism.

Actually -- I would like to completely ignore the theme - and awkward figures - and just view it as something like a colorful head scarf.

Like a tapestry it serves much better to enliven a wall than as a window into an imaginary world.

Otto Van Veen (1556-1629), Triumph of the Catholic Church, c. 1620

(Not in this exhibit)

More progressive and influential proved to be the contemporary efforts of Rubens teacher, Otto Van Veen, who advanced a stolid new form of classicism characterized by an unprecedented stillness and substance

Conceived as a processional with biblical and allegorical figures, the Triumph of the Catholic Church shows all the power, authority, and dogmatic earnestness of van Veen's heavy art.

Giotto’s figures were heavy and earnest as well,

but they were not so wooden and broken as these.

Otto Van Veen, Allegory of the Temptations of Youth (undated)

(Not in this exhibit)

In addition to substantial altarpieces, van Veen also painted elaborate allegories with mythological figures, like his Allegory of the Temptations of Youth (inscribed: typvs inconsvlte ivventvis, "image of thoughtless youth") which depicts a young man tumbled to the ground by Cupid and Venus, who sprays a stream of milk from her breast at his mouth, while Bacchus extends a shell full of wine toward him. Their assault is countered by the god of Time, who restrains Venus, while Minerva, goddess of Wisdom, deflects the stream of milk. The painting expresses an obvious moral message. In dwelling on the struggle between sin and virtue, between human lusts and appetites, and chastity and abstemiousness, the work expresses a spirit of stoic restraint and reason that Rubens later often adopted in his own allegories.? The greater animation of this allegory relative to the Triumph shows that while van Veen's personal artistic instincts favored a static ponderousness he could energize his figures when the subject called for it.

Van Veen looks good in overall pattern - and in a few select areas of detail.

Otto van Veen, Amazons and Scythians (no date)

(not in this exhibit)

This piece feels like a miniature - though it’s 6 feet wide.

It reminds me of this one - which really is a book sized miniature:

Jean Bourdichon, Bathsheba, 1498

It’s quite modest compared to Ruben’s’ "Battle of the Amazons",

and I wish it were painted by Titian,

but the theme is so sweet and dreamy.

What could be more alluring ( as well as puzzling) than warrior women

throwing off their armor to present their naked bodies to an army of grateful guys.

Rubens, Battle of the Amazons, 1617-18

(not in this exhibit)

Abraham Janssens, Pan and Syrinx, 1620

A far more original and trenchantly plastic classicism was developed around 1605-1607 by an Antwerp painter who was nearly a generation younger than either van Veen or van Noort. Abraham Janssens's(ca. 1574-1632) importance for seventeenth-century Flemish painting has surely been underestimated. He was the most talented history painter active in Antwerp during the years immediately preceding Rubens's return from Italy. Jansens perfected his own forceful new style with large, monumentally conceived figures of an unprecedented sculptural solidity, but with a capacity for graceful movement.

Quite sculptural indeed - the above is the best example that I could find - probably because it's just two figures and some drapery. I like this artist's luminosity and sense of volume - but I'm uncomfortable in the surrounding space. It feels like all the air has been sucked out.

His earliest dated painting, the Diana and Callisto of 1601 still is conceived in the tradition of late mannerist art, recalling more diminutive paintings by Hans Rottenhammer (1564-1625) or even Paolo Fiammingo. However the figures already display a new and vaguely pneumatic buoyancy that has more in common with the art of Jacopo Palma than that of any Northern artist.

Janssens, Adoration of the Magi, c. 1605

By 1605 Jansens had achieved a greater plasticity, stronger contrasts of light and shade, and a new brillance of color (see the Adoration of the Magi, dated 1605.. With a less crowded and more subdued composition, the Saint Luke Altarpiece of 1606 and the gracefully resolved and monumental Raising of Lazarus dated 1607

Abraham Janssens, Mary Magdalene, early 1620's ??

The artist's densely compacted, half-figure compositions constitute a separate group. They are difficult to situate chronologically, but few seem to predate ca. 1610, and again owe more to northern precedents (Jan van Hemessen, Jan Massys, Frans Floris, Abraham Bloemaert, and, of course, Rubens) than to Caravaggio. The splendor and coloristic opulence of these works is especially well appreciated in Janssens's Mary Magdalene.

Simone Vouet, Mary Magdalen, 1614-15

Here’s a contemporary French version,

also showing the eyes looking aside

but more prim and saint-like,

less voluptuous, less sumptuous.

(BTW - Wikipedia has a long list of paintings on this subject)

Janssens, Heracles and Omphale, 1607

Thank

The Hercules and Omphale, also dated 1607 resolves its athletic composition with far greater confidence and agility than, for example, van Veen's only slightly earlier allegory. The subject is the playfully erotic story told by Ovid in which Hercules successfully seduced the Lydian queen with wine, kicking the pesky Pan out of their bed, in effect assuming the lascivious fawn's role. Hercules' blindly obsessive love for Omphale threatened to emasculate the hero; a more commonly depicted episode from their love story shows the two figures reversing the attributes of their gender roles. For the seventeenth century, the debasement and humiliation of Hercules, usually an exemplar of virtue, carried a clear moral warning against the destructive potential of lust.

Edouard Joseph Dantan, Hercules and Omphale, 1874

This gender role reversal has inspired painters for two millennia.

I prefer Dantan’s version. It may not rise above illustration,

but it’s so bright, airy, and … um…. silly.

The Janssens feels claustrophobic and cluttered -

despite its "trenchantly plastic classicism"

Janssens, Venus and Adonis, 1620

Also from the 1620s are several handsome bucolic outdoor scenes which Jansens executed in collaboration with the landscapist Jan Wildens (1586-1653);

see, for example, the Venus and Adonis

Not really a painting - more like a pleasant wall covering.

Not especially erotic, despite the subject.

Not really human bodies - more like a collection of parts at a doll makers shop.

Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568-1625), Flowers in Wooden Vessel, 1606-7 (detail)

Pieter Brueghel the Elder ( 1525/30 - 1569) was a hard act to follow. Jan was only one year old when Pieter died, but he still grew up among artists.

I prefer the floral, shown above, to his many history paintings.

It is wonderfully intense, complex, and eruptive.

Pieter Brueghel the younger (1564-1638), Country Brawl, 1610

Here is Jan’s older brother - working in the idiom of his father.

It’s uglier - but so too, perhaps, we’re the times.

He could have been a Chicago Imagist.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Triumph of Death, c. 1562

Jan Brueghel the Elder, Triumph of Death, undated

Sutton points out that Jan copied one of his father’s most famous paintings.

Many of the differences could be accounted for by aging, restoration, or quality of online reproduction. But still — a different spirit seems to inhabit each.

Jan lives up to his nickname: "velvet Brueghel"

Pieter was cut from a coarser cloth.

Cardinal Federigo Borromeo

"Even the most insignificant works of Jan Brueghel show how much grace and spirit there is in his art. One can admire at the same time its greatness and its delicacy."

Frans Franken the Younger, (1581-1642)

Cabinet of a collector, 1617

Frans Francken the Younger, Power of Love

Tobias Verhaecht, Alpine landscape, 1600-1615

Sutton tells us that Verhaecht (1561-1631) was Ruben’s’ first teacher (for two years), but gives him no further mention - presumably because Rubens did not follow him into landscape painting.

But I enjoy his cosmic, fantastic, panoramic visions.

They remind me of this earlier Flemish piece that I grew up with in Cincinnati:

Joachim Patinir, Sacrifice of Isaac, c. 1540

Patinir is credited as the pioneer of "world landscape"

Adam Van Noort (1562-1641), John the Baptist, 1601

This is another of Ruben’s’ teachers.

Sutton has nothing to show us since he left " little or any stylistic influence"

on his two famous students, Rubens and Jordaens.

He does appear more proper than inspiring.

*******