William Henry Fox Talbot, The Open Door, 1844

OF THE THREADS THAT TIE the nineteenth century into a coherent whole, none, perhaps, is more compelling than that century's obsession with issues of "objective" reality and perception. In the area of painting, particularly in France, landscape became the primary testing ground for this obsession. Landscape painting was less bound than other types by academic rules and regulations and could easily be checked against reality; and the land itself, in the face of nineteenth-century urbanization, had taken on the additional romantic appeal of a place of escape and the potential victim of extinction. While the artist might choose to work from nature or not, a certain level of verisimilitude was a growing expectation in nineteenth-century France, and artists began to search for ways to unite "objective" reality with artful perception. Many "new" arts were uncovered as part of this search, including British watercolors and seventeenth-century Dutch painting. None, however, was more significant than the tandem discoveries of photography and East Asian art, especially the Japanese print. Together, they provided artists with both the motivation and the structure to generate the profoundly new aesthetic premises of the modern age.

I'm stunned by the boldness of speculating that an entire century of human history had an specific obsession - and I'm surprised by the notion that landscape painting was its primary testing ground in the 19th Century.

We may indeed note that those who now call themselves "objectivists" (the Ayn Rand enthusiasts) look to the nineteenth century French Academy of Bouguereau and Meissonier as the standard of truth in painting. But isn't their taste in art exceptionally narrow, insensitive, prosaic, and, thankfully, marginalized ? And what kind of objectivism could possibly encompass a Ukiyo-e print?

Johnson will go on to make several compelling connections between photography, Japanese prints, and a few French painters of mid 19th century Paris -- but the overstatements in this introduction are not very promising.

The photograph was immediately accepted as the ultimate statement of visual truth in science and art. The "truthfulness" of the Japanese print was also lauded, however- a surprising position given the premises of decorativeness and non-illusionism fundamental to the print. Through the elements shared in common by the print and the photograph, the photograph gave impeccable credibility to the print. This, in turn, allowed access to and understanding of the print's essential abstraction . Without the precedent of photography, it is unlikely that the Japanese print (and East Asian art in general) would have captured western artistic imagination as significantly as it did.

No footnotes accompany the above assertions - and none of them are especially obvious. The use of the passive voice is regrettable. No evidence has been offered that the emergence of both photography and Asian art in the years following 1834 was less coincidental than whatever else also emerged in those years.

Louis Daguerre, Fossils and Shells, 1839

Daguerre and Talbot are the two pioneers of photography - and they make for an interesting contrast. Daguerre produced spectacles for popular entertainment, Talbot was a gentleman with the time and means to exercise his sharp and curious mind. "Fossils and Shells" is packed with wonder and mystery; "The Open Door" is more casual and desultory. You might walk through that doorway - or you might not.

The first large exhibitions of photography were under the category of "Science and Art"

Baudelaire's response is quoted as follows: "Photography's real task....is in being the servant of science and art, but a very humble servant like typography and stenography, which neither created nor improved literature"

Johnson assures us that "the kind of photography against which he spoke, however, was that patterned after paintings he disliked equally.... sentimental, moralist, and maudlin .. heavily reliant on the realistic credibility of form for impact"

Yet Johnson did not share any of Baudelaire's positive critiques of photography.Maybe he would have spoken differently had he seen the art photography of the next century. Or, maybe not.

Henri-Jean-Louis Le Secq : North Porch, Chartres , 1852

Baudelaire's quote would certainly apply to the above - one of the photos of treasured monuments commissioned by the French government to promote their restoration. Called the "Missions Héliographiques" project, Johnson offers it as a prime example of the "confrontation between aesthetic convention and empiricism" --- though here they seem more congruent than confrontational. The camera can be used to capture the formal ideas of architecture and sculpture. Nature, however, offers us forms, not formal ideas, so the photographer must hunt for his own. And that's exactly what Charles Marville appears to have done with the sinuous lines of foliage and heavy masses of rocks he framed below:

It's no surprise that Marville had been trained in painting and then practiced illustration for 17 years before taking up the camera.

I'm guessing that Corot is the one at the top - as he should be !

This certainly proves that painters and photographers sometimes collaborated. And it's a fine photograph - presenting eruptive natural forces rather than a scenic view for daydreaming.

presented as a fine example of :

"alternative pictorial structures"

It may have been Edmond de Goncourt in his book on Utamaro of 1891 who first noted that photography and the Japanese print offered certain mutually supportive pictorial systems. On the most fundamental level, both the photograph and the print presented a destabilized definition of reality, at least in terms of traditional structure. Paintings in the dominant western Renaissance tradition were typically contained and finite, the proverbial "window onto the world" in which a box of space, clearly defined by non-intrusive framing edges, presented that world as calculable and whole. In contrast, the photograph and the print presented a fragmentary view of the world based upon discontinuous forms and unexpected juxtapositions. The factors generating this fragmentary view differed.

Here's the most unconventional old-master landscape that I could find after a brief search. There's an unsettling contrast between its four areas of interest (clouds, stump, tower, travelers). It doesn't really feel much like a " box of space .. that presented that world as calculable and whole". The word "destabilized" might apply.

But still it is "clearly defined by non-intrusive framing edges. It would benefit from an elaborate picture frame. The Japanese print would not.

The early photographer, only moderately in charge of the edges of the image, unavoidably truncated incidental objects while focusing on the real point of interest ; it is part of the genius of photography that as its aesthetic matured, "haphazard" cropping was exploited as a positive characteristic, evolving into the genres of the instantaneus and the snapshot, and eventually influencing painting attitudes. Similarly, the absence of finite framing edges in Japanese art was inherent from its beginnings in the scroll form . Within this format, space literally unrolled as narrative continuity without definitive beginning, middle, or end. As ukiyo-e developed, printmakers saw no need to restrict themselves to the small and regularized sizes of the woodblock- although the block itself might end, the image frequently spilled over onto several other blocks, resulting in similarly truncated forms . One need only compare a typically stable and timeless landscape in the Renaissance tradition from early in the century with a more random, destabilized image after mid-century to appreciate the radical shift in reality-definition this represents.

The early photographer - indeed, any photographer - is also only moderately in charge of pictorial space. Spacial relationships can be accurately depicted - but they cannot be intensely felt. They cannot express an artist's form making spirit. (even if they can express the spirit of the sculptor or architect whose work has been photographed)

Johnson offers a full page to photography versus painting as understood in mid-century Paris. I can appreciate why "with Baudelaire, photography became the polemic with which to attack the Realist painters" But since no visual examples accompany the text, I will not address it. In my own view, the highest non-mimentic qualities of photography are conceptual rather than formal, and therefore should be on temporary rather than permanent display in art museums. ( Mostly, it is )

No painter was more substantively influenced by the principles of photographic light and effet than Corot. It has frequently been noted that around 1848, Corot's style and apparent interests shifted dramatically. From an early style heavily dependent on architctural structure, hard-edged linearity, and geometrically based formal relationships, Corot broke through to an overwhelming concern with light effects, particularly with light as it dematerialized the earlier solidity of his forms. The result was a new and sweeping atmospheric veil that would be impossible to explain without the precedent of the paper photograph. His "sacrifice of detail" for a "feeling of extreme softness " is a virtual illustration of Le Gray 's pronouncements; but more specifically, the blurring of leaves against the sky and halo of light around these forms -the latter an unavoidable chemical phenomenon known as "halation" - specifically point to the paper print with a coated glass negative popular after 1850 as source.

Significantly, this technique also de-emphasized dramatic tonal contrasts in favor of a more even gray cast, a kind of "tonalism" that is predominant throughout Corot's middle period. The interest in photographic light is no doubt key to understanding Corot's intense involvement with cliche-verre during this same period ; the process provided a means to test and check light and relative values as a natural phenomenon literally created by the sun. This experimentation with value and tone is the primary link among most of his cliches-verre, as well as an insistent graphic quality also apparent in his paintings at this time. In the latter, silhouettes of trees rendered stark against the sky are full of the charged and nervousmark-making exploited in the cliches-verre. Not coincidentally, these qualities were also commonly found in early paper prints in which the middle tones had been dropped out, emphasizing silhouette, edge, and linearity . In all three - Corot's paintings of the period, his cliches-verre, and early paper photographs -this encouraged a wealth of illusionistic surface incident, touch, and a kind of painterly quality that grew increasingly autonomous In fact, it must be considered that the phenomenon of autonomous brushstroke as it evolved into Impressionism had among its immediate predecessors not only Corot, as is traditionally asserted, but the mid century landscape photograph with its rich and abstract surface activity..

In cliche-verre, the artist manipulates a negative that will be printed, just like a photograph, onto light sensitive paper. Typically the negative is a translucent sheet that has been coated with a black film that can be rubbed or scratched off so that light can pass through.

It allows for a very delicate touch --- as well as an infinity of tone. You can see above how Corot made one series of marks much lighter than the others. And where he coated one central area with a thick enough coat to totally block the light (so that the area would appear a bright white in the print)

Hokusai, detail from the Manga

Nobody could have felt the humble symbiosis of humanity and nature as expressed in the Manga (Hokusai) more than Millet, who, at least by the early 1860's owned a volume from the series.

... both stressed a charged, dynamic, information-laden line.

The point is well taken : linking Millet's drawing to the Hokusai Manga in his collection.

The "charged, dynamic, information laden line" is not typical of early 19th century academic or Romantic drawing - yet it might be seen in the Louvre.

It was certainly done in earlier centuries.

The "charged, dynamic" line was also not typical of Japanese prints.

Usually you get the kind of fine, even line shown above.

Millet, 1867

Regarding the influence of Japanese prints on Millet's paintings and pastels, I can't find examples of

"bright primary hues without interceding halftones"

The two pieces shown above do seem to have: "highly keyed contrasts", "general intensity", and an "aspatial, surface oriented image by precluding modeling in depth"

But can't that be found in pre-1850 European landscape as well?

Both Giroux and Bertin are about 15 years older than Millet, yet these landscapes have similar, non-academic qualities. ( I could not find a date for these pieces)

And here's a piece that has many of the qualities of photography and Japanese prints, yet it predates their arrival in France by nearly a decade.

(it reminds me of the romanticism of Girodet)

There is a sense of wonder in the Millet pieces -- but is that especially related to Japanese prints ?

Millet also seemed consciously to manipulate perspective and works which after 1865 grew increasingly strange and dramatic. Once again this was most apparent in his drawings. While the looming anatomic components of Meridian of 1865 have been compared to photographic idiosyncrasies, this type of frontal plane distortion would have been actively eliminated in the early photograph, especially in figure compositions. Instead, the unusual worm's-eye vantage point and resultant inversion of spatial recession better suggest the witty effects in certain plates of Hiroshige's 100 Views of Famous Places in Edo , well known by this date. Moreover, the figure in Millet's work has a decisive object quality - as if it could as easily be a haystack as a figure - underscoring a possible source in study of Hiroshige's landscape prints.

Hiroshige, Summer, from 100 Views of Edo

Yes, there is a playfulness of perspective in this series--- as if that was Hiroshige's main concern.

We might also assume that such spatial playfulness was intended in the drawing shown above - though, since I did it myself, I can assure you that it was only the result of my circumstantial point of view on a reclining model at the art club.

BTW - I really like the figurative volumes in Millet's "Meridian". It reminds me of Diego Rivera (now better known as the husband of Frida)

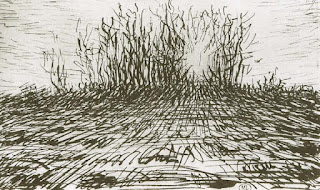

Similarly, works like Entrance to the Forest of Barbizon in Winter of 1866-67 rely for much of their effect on Millet's urge to flatten space. The drawing, although a reworking of earlier ideas, is also suggestive of the spirit and aesthetic of Hiroshige's popular landscapes of the 1840s and 1850s: it is resolutely vertical in its push to the surface plane, especially via chalky wisps of snow which spot the surface and in the projection of highest light from the scene's apparent background; it is redolent with atmospheric space - identified as western influence when it appears in Hiroshige - which subtly pulls against the flattening impulse; and it is evocative of the quiet, spirit-laden presence identified

I also feel both the "spirit-laden presence" and the dramatic push and pull of pictorial space.

As a viewer, I am pulled right up to the gate of the forest - so that the foliage and wisps of snow in the foreground are actually behind me. It's a thrilling sensation.

Johnson's connection of Millet to Hiroshige and Hokusai is my principal takeaway from this essay.