This is Chapter 10 of Eric Kandel's "The Age of Insight : The Quest to Understand the Unconscious in Art, Mind, and Brain".

Quoted text is in YELLOW. Text quoted from other authors is in GREEN *************************************************************************** ****************************************************************************

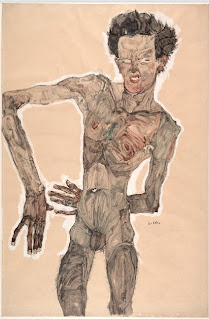

IN HIS PALPABLE EXISTENTiAL ANXIETY, EGON SCRHELE is the Franz Kafka of modern painting. While Gustav Klimt and Oskar Kokoschka, spurred by their intellectual contemporaries, took an interest in the inner lives of their subjects, Schiele more than any other artist of his time took an interest in his own anxiety. He expresses this deep anxiety—as if his private world were coming apart—in numerous self-portraits, and he superimposes a corresponding anxiety on everyone he painted, including the people in the dual portraits of his sexual experiences. There is, in those portraits, a frightening aloneness, even in union.

I've got to agree with Kandel's connection of Schiele to Kafka --- Schiele sees himself as a kind of insect --

and insects stay alive by living in perpetual anxiety.

And they can also be beautiful -- in a terrible kind of way

Reminds me of a punk-ish young woman who wore black lipstick and modeled for us a few years ago.

On her forearms she had self-tattooed the crudely lettered words: KILL -- FUCK -- EAT --- DIE

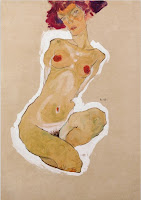

. Like Klimt and Kokoschka, he was preoccupied with aggression and death, but his work, unlike Klimt’s drawings of women enjoying their sexuality, conveys a wider range of female emotion in response to sex—torment, guilt, anxiety, sadness, rejection, curiosity, and even surprise. Especially in his early work, Schiele’s women appear to suffer their sensuality rather than enjoy it.

1912

This was the only example I could find of an early work where a woman appeared to suffer rather than enjoy her sensuality.

1910

If not just a figure study, his drawings often appear designed to satisfy a male taste for cheesecake -- like a pin-up girl.

In this sense, Schiele followed Kokoschka’s lead in attempting to probe deeply his own life and the lives of those he painted. But he differed from Kokoschka in several important regards. Rather than focusing exclusively on facial expressions and hand gestures to explore beneath the surface of his subjects and obtain insights into their character and conflicts, Schicle used the whole body. Also unlike Kokoschka, who frequently painted other people, Schicle often painted himself. He depicted himself as sad, anxious, deeply frightened, and sexually engaged with himself or with others.

Portrait of Gerti Schiele, 1909

As you can see from the above, Schiele came under the influence of Klimt who recognized his talent and encouraged him.

Portrait of Anton Peschka, 1909

Portrait of Anton Peschka, 1911

But as you see from these two portraits of his brother-in-law, he quickly moved on to a less decorative style

1910

A poor student in school, Schiele possessed an exceptional ability to draw. Based on that talent, he was admitted to the Vienna Academy of Ii iie Arts at age sixteen, where he was the youngest student in his class. He began to perfect his already formidable drawing skills by first simulating and then elaborating upon the technique of blind contour drawing that had been developed recently by the sculptor Auguste Rodin’ and adopted by Klimt. Schiele would observe his models and, without hiking his eyes off them or lifting his pencil off the paper, would draw their figures with extraordinary speed in one continuous line, which he never modified or erased.

Tlie result was a highly distinctive line that was at once nervous and precise—and very different from Klimt’s sensuous, Art Nouveau line or the meticulous and calculated rendering of the Viennese academic tradition. Using this new line, Schiele was able to capture the gestures and movements of his models and himself and to express them by means of contours rather than light and shadow. Schiele would continue to apply this drawing technique throughout his career, communicating evocative body language through the power of outline and silhouette.

Above is an example of an actual blind contour drawing - as shown on the internet in observance of an exercise in Nicolaides' "Natural Way to Draw", a popular instructional book first published in 1941.

Like Schiele's drawing shown above it, there is no sense of volume or space. But unlike Schiele's, there's also no sense of graphic design.

If the artist is not also looking at the paper, his lines cannot relate to it.

Schiele (and Rodin) definitely placed great emphasis on contour lines - and may well have drawn them without lifting the pencil off the paper. But his designs are too strong to have been done without looking at them.

Picasso, Portrait of Stravinsky, 1920

Same thing with the above drawing by Picasso.

Where did Kandel pick up the notion that Schiele made drawings without looking them? He doesn't provide any footnotes for it, and I can't find anything on Google beyond a brief mention on "How to Draw" websites.

The result was a highly distinctive line that was at once nervous and precise - and very different from Klimt's sensuous, Art Nouveau line or the meticulous and calculated rendering of the Viennese academic tradition.

There's no disputing that - and it does seem that the early 20th C. saw a brief but wonderful emergence of depiction that was both based on direct observation and strongly contoured. I can't think of another period of European, or even world, art history that compares with it. It disappeared as figurative depiction became either more decorative (Art Deco) or more angst ridden (Surrealism)

In his search for what lies below the surface of everyday life, Schiele, like Kokoschka, was a true contemporary of Freud and Schnitzler: he studied the psyche and believed implicitly that to understand another person’s unconscious processes, he had first to understand his own. Schiele exhibited himself compulsively in his drawings and paintings— All of Schiele’s self-portraits depict him in front of a mirror, sometimes in the act of masturbating

The paintings of himself masturbating are bold on several levels, not the least of which is that many people in Vienna at that time thought duit masturbation by men led to insanity.

But the self-portraits are not simply an exhibition of nudity; they are an attempt at full disclosure of the self, a self-analysis, a pictorial version of Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams. In an essay entitled “Live Flesh,” the philosopher and art critic Arthur Danto has written:

Eroticism and pictorial representation have co-existed since the beginning of art. .. . But Schiele was unique in making eroticism the defining motif of his impressive . . . oeuvre. [Schiele’s paintings] are like illustrations of a thesis of Sigmund Freud . . . that human reality is essentially sexual. What I mean is there is no art historical explanation of Schiele's vision.

An image search for "self portrait masturbating" only pulled up two examples -- and only one artist: Schiele.

So even back in Freud's Vienna, he may have been the only artist to depict that theme.

He doesn't look especially happy about it does he ?

self portrait, 1910

self portrait, 1910

Kandel asserts that both of the above self portraits also depict masturbation , but if so, then the same would be true for every solitary nude.

Richard Gerstl (1883-1908), self portrait

An image search for "nude self portrait" also brings very few results prior to contemporary sexting and post-modern photography.

But interestingly enough, it did find another Viennese contemporary of Schiele, Richard Gerstl, who regretfully killed himself after getting dumped by the wife of Arnold Schoenberg.

Gertstl: Portrait of the Schoenberg Family, 1908

Gerstl was quite a painter - it's too bad he lost control of his personal life.

Albrecht Durer, 1505

And here's a more famous nude self-portrait - this one done 500 years before Sigmund Freud.

And how would Kandel compare this to the self portraits by Schiele?

It does seem to have an expressive character - as well as angst.

Eroticism - aggression- anxiety ? Maybe.

But he definitely does not present himself as a clown or misfit or nut case.

(BTW - this drawing is currently in the Schloss Museum, Linz -- about 150 miles from Vienna. Was Schiele familiar with it ? )

Lucian Freud, "Painter working, reflection", 1993

And then, more recently, we have Sigmund Freud's grandson, in an image that may be nude but doesn't seem to have anything to do with sexuality.

And though you feel his soul has been laid bare -- he doesn't seem to be crazy at all -- just devoted to his calling.

In his 1915 Self_Portrait with Striped Armlets, Schiele presents himself as a social misfit, a clown or fool . The armlets, with their vertical stripes, recall the typical costume of a court jester. The artist has colored his hair bright orange, and his wide_open eyes hint at madness. His head tilts precariously from the top of a slender neck.

Similar to his contemporary, Picasso, who identified with Harlequin.

In another self-portrait, the force of his anxious expression is further heightened by the application of a thick white halo of gouache around the outlines of his head, isolating it and making it stand out against the background while at the same time making it appear large and deserving of emphasis. Moreover, Schiele depicts an immense territory above his eyes—a gigantic forehead and a deeply furrowed brow. This portrait suggests that Schiele may have wanted to recapitulate Klimt’s earlier depiction of the decapitated Holofernes, but with himself as the victim: he has placed his head at the top of the sheet of paper, emphasizing that his body is missing.

Rudolph Weisenborn (1881-1974)

Here's a self portrait by a Chicago artist from about the same time. He looks pretty angry and antisocial, but by comparison, Schiele looks like he belongs in a psychiatric hospital.

Quoting art historian, Allesadra Comini "Why did Schiele's work assume such imperious intensity at this time and how did he fashion a new artistic vocabulary that called for this concentrated vision"?

Was it because he had seen his father go mad from a syphilitic brain disorder ? Or because the cultural elite of Vienna were then so focused on the psyche ? A physician friend invited him to draw the patients in his mental clinic.

There seemed to be a greater curiosity regarding madness than sanity, possibly because physicians and scientists were so dominant among the cultural elite. So Man was more like a biological specimen than an active participant in either public or sacred narratives.

1918

Some of Schiele’s images, unlike those of the earlier artists, focus explicitly on genitalia and sexual acts. In Crouching Female Nude with Bent Head of 1918, for example, Schiele conveys a girl’s feelings by depicting her with her head deeply bowed and an expression of wistful melancholy on her face. Long, loose strands of hair frame her face, as if she were searching for protection and security.

Making Love, 1915

Some of Schiele’s images, unlike those of the earlier artists, focus explicitly on genitalia and sexual acts. In Crouching Female Nude with Bent Head of 1918, for example, Schiele conveys a girl’s feelings by depicting her with her head deeply bowed and an expression of wistful melancholy on her face. Long, loose strands of hair frame her face, as if she were searching for protection and security.

Making Love, 1915

In paintings such as Love Making of 1915, sexuality, eroticism, world-weariness, exhuaustion, and fear fuse to express the inseparability of Eros and anxiety.

I don't feel any Eros in the embrace of these two puppets. Isn't this what you'd call "cuddling"?

Death and the Maiden, 1815

As Kandel explains it, this painting depicts the artist and his mistress, Wally, at that delicate moment after they have made love and he has decided to dump her Self centered as the artist may have been, this character does seem to express remorse regarding his soon-to-be-abandoned lover - as the artist seeks a more socially acceptable match.

So more than just psychological, this painting is also interpersonal -- and maybe even moral - as the artist sees his lover as vulnerable and himself as a wretch.

I wonder what happened to Wally?

She probably outlived Egon who died three years later.

But unlike Picasso's early mistresses, she vanished from the public eye.

Death and the Maiden is often compared to Kokoschka’s The Wind’s Iiancée, depicting his tumultuous relationship with Alma Mahier, but the two paintings are actually quite different. In both works, the men are anxious, but in The Wind Fiancée Alma Mahler is sleeping calmly, whereas in Death and the Maiden Wally is experiencing a sense of isolation and desperation comparable to Schiele’s own. She senses abandonment, he a lack of fulfillment. In Schiele’s world no one is ever safe.

It's too bad these two paintings cannot be permanently displayed side by side. Have any earlier paintings in art history depicted the emotional disasters of romantic love as frankly as these two ? The only thing worse than a lover who clings -- is a lover who doesn't.

The doppelganger, a popular theme of German Romantic literature, is the ghostly counterpart of a person who acts just as the person does. Although the doppe1ganger can take the form of a protector or imaginary companion, it is often a harbinger of death. In folklore, the doppe1gnger is a phantom of the self: it casts no shadow and has no reflection in a mirror. Schiele uses the doppelgänger in both senses in his double self-portraits. In Death and Man (Self-Seers II) of 1911, Schiele fuses what appears to be either his own face or his father’s face with the skeleton-like figure of death standing behind him. As with many of Schiele’s works, the image is both frightening and intriguing.

If, as Kandel asserts, this image relates to a physic phenomenon of German folk-lore, it hardly seems connected to Freud and modern medical science.

I can relate to it personally as a depiction of father and son - especially since that ghostly figure in the background resembles my own father in his last decade.

Hermits, 1912

“In the large painting one doesn’t see exactly how the two are standing there, at first glance ---this is important to the painting --- otherwise, the poetic idea and the vision would be lost, as would the ambiguity of the figures which, conceived as being crumpled into themselves, are the bodies of individuals who have grown tired of life, grown suicidal—but even so, they are people of emotion. —Think of these two as being like a cloud of dust similar to this Earth, a cloud which wants to grow into something more but must necessarily collapse, its strength spent.

........... Egon Schiele in a letter to an important German patron/collector of modern art

As Kandel notes, this double portrait of Schiele with Klimt echoes the one done by the youthful Kokoschka, where the young artist is leaning on the shoulder of the older one.

But in Schiele’s portrait, Klimt—Schiele’s irIistic father—is leaning on him for support. In 1912 Klimt was still at the peak of his career, the dominant force in the artistic world of Vienna, yet in the painting he seems barely to hang on, not only to Schiele to life itself. In fact, his wide, blank eyes suggest that he is blind. Schiele’s double portrait may well reflect the artist’s unconscious, Oedipal desire to eliminate his imagined rival, Klimt, and succeed him as Veiiiia’s top artist.

This is a small community, isn't it? With Klimt as the village headman. Did any other modern artist of that period take as much interest in mentoring the next generation of artists ? (and one might note -- Klimt was not teaching in an art school)

Would Kokoschka and Schiele have enjoyed the same early success without Klimt's involvement?

Cardinal and Nun (The Caress) 1912

Kandel shows us more evidence of Schiele's connection to Klimt, this parody of Klimt's "The Kiss", with Wally posing as the nun.

The guilt-ridden darkness of Schiele's version certainly brings out the romantic idealism in Klimt's.

Schiele's death marked the end of the expressionist era in Vienna, an era that saw the first step toward a potential dialogue between science and art. The five giants who emerged from Vienna 1900 could trace their immense accomplishments in psychoanalysis, literature, and art directly or indirectly to the the scientific influence of Rokitansky's view that surface appearances are deceptive and that to obtain the truth, we need to go deep below the surface

And so, with the premature death of Schiele from influenza in 1918, Kandel ends this chapter

Here are the paintings I could find from the last two years -- and they don't seem to be about an "inner truth" any more than the figure paintings of Manet, Eakins, Goya, and Rembrandt - to name just a few.

1918

When Schiele was living the Bohemian life -- that's what he painted.

1917

But now that he's becoming a respectable middle class family man - that seems to be where his vision is going.

1917

He still likes a little kinkyness - but nothing that would shock a banker.

1917

And he's even moving into cute.

1917

No comments:

Post a Comment