This is Chapter 18 of Eric Kandel's "The Age of Insight : The Quest to Understand the Unconscious in Art, Mind, and Brain".

Quoted text is in YELLOW. Text quoted from other authors is in GREEN *************************************************************************** ****************************************************************************

Klimt, Field of Poppies, 1907

WHEN A GREAT ARTIST CREATES AN IMAGE OUT OF HIS OR HER OWN experience, that image is inherently ambiguous. As a result, the meaning of the image depends upon each viewer’s associations, know1edge of the world and of art, and ability to recall that knowledge and bring to bear on the particular image. This is the basis of the beholder's share—the re-creation of a work of art by the viewer. Cultural symbols, recalled from memory, are similarly critical for the producing and viewing of art. This has led Ernst Gombrich to argue that memory plays a critical role in the perception of art. In fact, as Gombrich emphasized, every painting owes more to other paintings than it does to its own internal content.

That might indeed serve as an article of faith among art historians. But on the contrary, one might assert that internal content is what makes a painting part of art history in the first place - even if that assertion contradicts the Institutional theory of art.

One might add that, barring physical deterioration, internal content never changes - while memory is transitory.

If, for example, we look at a landscape painted by Gustav Klimt, such as A Field of Poppies it is difficult to ascertain the meaning of the image from the internal content alone. What is immediately apparent is a homogenous expanse of green paint, punctuated with spots of red, blue, yellow, and white, stabilized by two small passages of white at the top edge of the canvas. Once we compare this image to what we know about painting, however, the content of the picture becomes perfectly clear. Considered in the tradition of landscape painting, specifically that of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist pointillists, what emerges from the mass of green and red splotches is a beautiful pastoral scene of a poppy field covered in flowers. Even though the two trees in the foreground are difficult to distinguish from the field of flowers they are growing in.

The beholder is easily able to construct a figure ground relationship between the two because he or she knows to look for them

Doesn't the search for the meaning of a painting -- or indeed anything --- begin with determining what one is looking for ?

If we had sent Klimt to explore a remote island and this painting was included in his report -- yes, it would be very important for us to identify the trees, flowers, topography, etc, that he was depicting.

Or -- if we were trying to connect Klimt to the history of art -- then it would be important to know about Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Pointilism etc.

But if we're just looking for what might be thrilling, satisfying, and distinctive about one artist's unique visual world --- none of the above is necessarily relevant.

Klimt's Poppy Field feels like an overwhelming, all-encompassing sensual experience -- as one might feel in a room dominated by the above 16th C. Persian carpet.

As this brief essay explains, there are many and various motifs to be found in this genre.

But does enumerating them even begin to describe the mood that the piece has created?

Or -- what about enumerating the flora and fauna in the 'Narcissus' tapestry from Boston ?

The greater realism in Klimt's poppy field needs no scholarly footnotes to explain.

Unlike the two tapestries shown above, there's an horizon line -- and the spots get smaller and more tightly compacted as one moves deeper into the imagined pictorial box -- just as they would if you were standing in an actual poppy field.

Is sensing this depth of pictorial space a "top-down" or "bottom-up" mental activity ?

Information processed from the bottom up relies in good part on the built-in architecture of the early stages of the visual system, which is largely the same for all viewers of a work of art. In contrast, down processing relies on mechanisms that assign categories and meaning and on prior knowledge, which is stored as memory in other regions of the brain. As a result, top-down processing is unique in each viewer

But isn't bottom up mental activity unique to each individual as well ? Even if categories and meaning is not being assigned, aren't visual patterns and rhythms felt differently among various individuals ?

Here are four versions of another painting of a poppy field - the original done in 1873 by Claude Monet.

The above is the reproduction provided online by the Musee D'Orsay.

Here's a version that seems to have been through photoshop to juice up the colors and contrasts.

Here's a re-painted version that makes the figures and the house more distinct.

And here's another re-painted version for people who really like big red poppies.

Top-down : all that distinguishes them is the provenance of the image. All four have identical categories of objects (trees, poppies, house, umbrella, child, etc) on display in relatively identical positions.

But bottom-up, some of these images are far more preferable to some people than to others.

I suspect that the one from the D'Orsay is closest to how the painting now appears -- though the bright redness of the poppies may have dramatically faded over the past 140 years.

For me, the photoshop version is badly mangled -- while the two re-paintings are monstrosities.

But that's just my lame brain going from bottom to top --- obviously many other brains feel quite differently.

THE IMPORTANCE OF top-down processing and the effects of attenion and memory on perception are immediately evident in viewing a work of art. To begin with, the attention of a person viewing a work of .art differs in important ways from what the student of perception Pascal Mamassian of the University of Paris calls “everyday perception.” In everyday perception the task is specified. If you are going to cross ii ic street, you watch for a break in the traffic before starting. Your perception is therefore highly focused on the cars coming by, their speed and size, and you disregard irrelevant information such as whether a particular car is a Buick or a Mercedes-Benz, whether it is gray or blue. It is much more difficult to identify an appropriate task in the perception of visual arts. Indeed, the viewer approaches a work of art differently, and his or her response can depend on where he or she is standing. The artist, in turn, faces the challenge of not knowing where the beholder will stand -and viewing angle can greatly affect the beholder's interpretation of a three-dimensional scene.

Yes -- just what is an "appropriate task in the viewing of a work of art"?

I'm glad Kandel told us that it is "difficult to identify"

But his first response is to suggest that the viewer's response can depend on where the viewer is standing - and quotes Pascal Mamassian who asserts that "the only viewpoint from where the painting is a faithful rendition of the scene is the center of projection, that is the location where the painter was standing if the scene was painted on a transparent canvas"

I find this emphasis on the viewer's position puzzling, to say the least -- mostly because I doubt both the clarity and importance of whatever Kandel and Mamassin might mean by the phrase "faithful rendition"

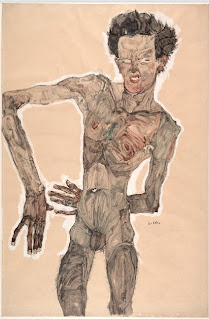

Gustav Klimt, 1917

The only example that Kandel offers is the above drawing by Klimt

Understanding the nature of this top-down phenomenon as it pertains to where the beholder is standing teaches us a great deal about how we perceive paintings. The best-known example is when the eyes of the subject of a portrait follow us wherever we stand. This effect which we see in Gustav Klimt’s beautiful portrait depends on the sitter’s having been painted looking at the painter’s eyes: The pupils of the sitter’s eyes will then be centered on our own eyes. When we move to the side, the position of the eye becomes distorted, but top-down perceptual system corrects for this distortion. As a result the pupil of the sitter’s eye is not altered very much, even though other distortions occur in the painting. This accounts for the illusion that the eyes of the subject follow us as we move. If the perspective in the painting were perfect, as it is in a sculpture, the portrait would look distorted from every perspective except one. Thus, if we view a bust from the side, the pupil of the eye appears asymmetrical and does not appear to be looking at us.

Wouldn't it be sufficient to say that a piece should be viewed from wherever it looks the best?

Kandel is following Manmassian who is following Gombrich who emphasizes pictorial realism in the history of Western European art. It's an approach that appeals to a scientific mind - but ignores how often realistic criteria - especially the single P.O.V. so important to Mamassian - have been ignored before, during, and after the Renaissance.

But then, curiously enough, Kandel argues the antithesis : "the appreciation of art, and even our understanding of what it represents, does not depend on our assuming any specific viewing position."

Then he quotes the cognitive psychologist, Patrick Cavanagh :The tolerance of flat representations is found in all cultures, infants, and in in other species, so it cannot result from learning a convention of representation."

Then he refers to Michael Polanyi ("Meaning", 1975) who distinguished focal awareness (of "the person or scene depicted") from subsidiary awareness (of brushstrokes, marks etc) when viewing a painting.

This Van Gogh self portrait is offered as an example of those two states of awareness.

But can the mind distinguish "the person or scene depicted" from the character and arrangement of the marks from which that depiction is recognized ?

Perhaps so -- if that mind is trying to identify the depicted details to answer questions like "who is this man?" or "what is he wearing?"

But what if the mind is asking "how do I feel about this image?" - as my mind would ask when looking at works of art. In that inquiry, the awareness of brushstrokes is not subsidiary to anything.

Some day, I suppose, I'll have to locate a copy of Polanyi's "Meaning" to discover how he got into his discussion of the viewing of paintings. Perhaps it's how he personally looks at art works.

Caravaggio. "Supper at Emmaus"

Regarding Kandel's discussion of viewing position -- I think it is important to assume the specific viewing position suggested by the painting. But it does not have to be one specific point. In the "Supper at Emmaus", the fractured perspective is pulling the viewer across the table, right up to the chest of Christ. (that's why the near and distant hands of the man on the right are the same size)

Although the aesthetic experience of a work of art is greater than the sum of its parts, the visual experience begins in this mosaic fashion, with a scanning of all the parts, one feature at a time.. The importance of different types of scanning movements in picking out the essential elements in a painting is illustrated in the following examples:

Klimt: Adele Bloch-Bauer II

Klimt: Adele Bloch-Bauer I

Klimt: Judith

Klimt’s three images of women—two of Adele Bloch-Bauer and one of Judith—differ primarily in their facial expression. In the top image, Adele is neutral, almost bored; in the second, she is modestly seductive; in the third, Judith, in the afterglow of sexual rapture, appears both victorious and ready for more encounters. But what is perhaps equally striking is how much of our visual attention, particularly for Adele Block-Bauer I and Adele Block-Bauer II, is expended on details having nothing to do with the sitter’s face, such as her richly ornamented gowns, which meld almost imperceptibly into the background. .... Thus in viewing Klimt's portraits, our eyes are multitasking: they scan the image as a whole to obtain a sense of the various ideas the artist is trying to convey.

Here's Klimt's portrait of Adele -- with everything but the face taken out.

To demonstrate -- I think --- that Klimt's background is giving Adele personality and character, as well as establishing her opulent queen-like social status.

And, at least to my sensibilities, she's only "modestly seductive" when that intense, formidable background has been removed -- but then, perhaps that's just because my own middle class background is intimidated by all that bling.

Regarding "multitasking" --- isn't that how one looks at something as art -- feeling whatever can be felt and relating to whatever memories are accessed at that moment?

In contrast, Van Gogh and Kokoschka invite the viewer to focus primarily on facial expression. Each visage is unique and memorable. The richly textured background serves only to highlight the emotion that emerges from the facial features. Thus, in viewing Klimt's portraits, our eyes are multitasking: they scan the image as a whole to obtain a sense of the various ideas the artist is trying to convey. In Kokoschka's portraits, our attention is tightly focused on the essential facial expression of each subject and the meaning of that expression.

And here is Kokoshka's portrait of Blumner with everything gone but the face.

The background did seem to "highlight the emotion that emerges from the facial features"

Though you could also say that the face highlights the emotion emerging from the background, so I would not agree with Kandel's assertion that "in Kokoschka's portraits, our attention is tightly focused on the essential facial expression of each subject and the meahing of that expression"

And I don't think you could say the same for those Klimt portraits -- where the naturalistic face almost feels like it's been cut and pasted into a different kind of painting.

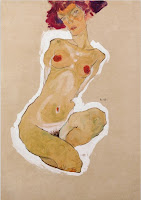

A very different type of contrast emerges from Kokoschka’s and Schiele’s depictions of themselves with a lover. Kokoschka painted several romantic dual portraits of himself with Alma Mahler, but none of them speaks of consummation. In all of them Kokoschka appears passive, swept along by forces beyond his control. That impression is enhanced in The Wind’s Fiancée by the turbulent waves that surround the two lovers and that are beyond Kokoschka’s ability to control. Schiele, in contrast, specializes in raw sex: no lack of consummation here. But it is a sexual union in which the bliss of romance and erotic pleasure is counterbalanced or even overridden by anxiety. The mixture of conflicting instinctual drives cancels out any pleasurable component of sex, resulting in an emptiness—the emptiness of union—which can be seen in the eyes of the subjects. In Schiele’s portraits, the anxiety connected with sex is so great, and the sheer power of the emotion so strong, that he appears to need no tempest, no background effects, to dramatize it further.

The artists’ stylistic differences—differences that our eyes take in all at once—convey different emotional content.

Seitei School, 1900-1910

By way of even greater contrast, here's a mating couple from the same decade, though from a very different tradition.

The personality of the lovers is absent. Other than for the animation of their coupling, they are plant-like. The turbulence is completely biological. Their sex is a beautiful moment, rather than an emotional crisis of self identity - and it's more of a dream-like fantasy than a record of personal experience.

But why did Kandel compare those two paintings anyway ? His only conclusion is that "The artists’ stylistic differences—differences that our eyes take in all at once—convey different emotional content""

--- which could be said about any two images.

His discussion of the top-down or bottom-up perception of visual art has been rather thin, and does nothing to establish that the art viewing mind doesn't continuously bounce back and forth between top, bottom, and all points in between.