Quoted text is in YELLOW. Text quoted from other authors is in GREEN)

The frescoes painted by Giotto in the Arena Chapel at Padua, about the year 1305, mark an entirely new stage in the development of empirical perspective, as in that of every other aspect of pictorial art. In his depiction of the human figure the emphasis on weight and volume is as striking as his concentration, as a storyteller, upon the dramatic essentials. The discursive interest in the haphazard detail of the visible world, characteristic of Assisi, is noticeably lacking here.

White has chosen to ignore

paintings like this one

at Assisi.

What's missing at Padua

is the more Byzantine style

of Cimabue and the Isaac Master

as well as the weaker collaborators.

It is therefore no surprise that the treatment of space betrays the same severe concentration. Out of this penetrating interest in the essentials both of nature and of art, a new relationship between pictorial space and the flat surface of the wall rapidly emerges. Giotto’s conception of what this relationship should be is vividly shown at Padua by the framework which surrounds the history scenes, uniting them to the architectural reality of the chapel.

Within this modest, barrel-vaulted rectangle, complicated only by the addition of the simplest of Gothic choirs, everything is planned for painting . There are no cornices, no raised mouldings. Six plain, untrimmed window openings are the only interruption in one otherwise unbroken side wall. Nothing interrupts the other. There are no columns, no pilasters,no ribs running in the vault. Without the painter there is nothing but the inarticulate, bare wall. This total bareness has the effect of giving the ambitious artist the maximum area of ideal painting surface whilst removing the element of competition. There is no need, and no temptation, to try to equate painted architecture with the natural volume and solidity of structural stone and marble. The lack of any wish to create a binding, over-all illusion is categorically stated by means of the plain red band which separates the marbled decoration of the walls at all four corners. The painted framework on each wall is a floating, decorative unit on the existing surface, and not a counterfeit wall in itself.

More than any other church,

the Arena Chapel does seem

to have been designed

strictly as a picture gallery.

Hats off to old man Scrovegni!

I can imagine Giotto

whining to him

about the goofy friars

and dim witted

collaborators he had at Assisi,

so Scrovegni put him in charge

of the entire project.

South wall

South wall North Wall

North WallThe most exciting development of all in the conception of the chapel as a single whole is the emergence of a tendency to adapt the viewpoints in the scenes themselves to that of a spectator standing at the centre of the building. This new conception is not reflected at all in the frescoes of ‘The Life of the Virgin’. These are seen haphazardly from left and right, regardless of their place upon the wall. In the scenes from the ‘Life of Christ’, however, the compositions themselves belie the neutrality of their frames. Apart from the ‘Noli Me Tangere’ and the ‘Pentecost’, they are all constructed so as to emphasize the centre of their respective walls. Even in the interiors the axis is displaced to left or right in harmony with the position of the middle of the wall to one side or the other. At Assisi the scenes were united by balancing their surface patterns one against the other. Here, although innumerable correspondences can be found between one row of frescoes and another, as well as between individual scenes, there seems to be no attempt at direct formal balance. The simplicity of the problem at Assisi, where only a single row of scenes needs organization, lends itself to such a solution, whereas the more complicated situation at Padua does not. Instead, the unification is achieved by perspective means.

Regarding whether the rectangular shapes

are oriented as to be seen

from the center of the chapel,

here's my count for the north and south walls:

Top row (life of the Virgin) : 5 (correct) , 4 (wrong), 1 (N/A)

middle row (early life of Christ) : 5 (correct) , 3 (wrong), 2 (N/A)

bottom row (passion of Christ) : 5 (correct) , 2 (wrong), 3 (N/A)

Assuming that these walls were painted

from the top to the bottom,

there is a gradual tendency

to orient the rectangles

towards the center of the chapel,

but is this really

"the most exciting development

in the conception of the chapel"?

And, as you can see,

there is an equally increasing tendency

not to include a rectangular shape at all,

(these are the scenes that I marked as "N/A")

The "wrong" ones on bottom row include:

"Noli Tangere" and "Pentacost" (as noted by White)

and the three "wrong" ones on the middle row include:

"Adoration", "Presentation", and "Massacre of Innocents"

north wall

north wallNow lets look at photos

of the entire wall.

(note: in 2011 they're still hard to find on the internet!

Why hasn't the Arena Chapel been given the same

thorough presentation as the Sistine?)

north wall

north wall south wall

south wall south wall

south wallSeveral sets of scenes do seem

to be composed with each other,

either vertically or horizontally,

and they also seem to work with the

windows beneath or between them.

... the first point of interest is that nearly all the buildings are obliquely set within the picture space. In the St. Francis cycle, and in Cavallini’s work in the ‘nineties, the foreshortened frontal setting was used in fully half the scenes. At Padua it only appears four times in all. And this includes one special case and the relatively minor example of the sarcophagus in the ‘Noli Me Tangere’.

The special case is that of the ‘Annunciation’, which takes place across the top of the triumphal arch.

Damn those counter-examples!

It's like continuing to use a sled

after the invention of the wheel.

White accounts for this backwardness as follows:

The great fourteenth-century painters were always ready to sacrifice the demands of external logic to the particular compositional problem with which they were faced. There was no fixed theory of perspective construction. There were no set rules to be obeyed or broken. Methods were empirical, based upon inherited skills, on personal observation, and upon the craftsman’s sense of what would give the best results in practice. In Giotto’s case, there is no doubt that the divergence seen in ‘The Annunciation’ is a matter of deliberate choice, and not of ignorance, or of indifference to a distinction which seemed unimportant to him.

The above would seem to apply to the artist of every painting worth looking at.

But what about the Christian visionary's sense of spiritual truth? As a secular scholar, White ignores that.

(Further discussion of Giotto's neglect of mathematically correct constructions can be found here , thanks to Philosophy Professor John H. Brown, University of Maryland.)

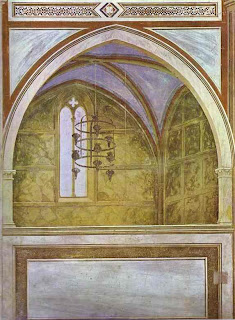

Lower down on the same wall are painted the upper parts of two small Gothic chapels, perfect in every detail of their vaulting . These are seen as if from the centre of the arch, in contrast to the buildings immediately above. Here there is no story to be told. No figures dominate the scene and influence the architectural construction through their paramount demands. What is desired is the illusion of two chapels flanking the existing choir, and everything is ordered for the benefit of an observer standing in the centre of the church. Here, where realism is supreme, the result is quite astounding, and the extreme importance of weighting the artist’s own intentions in attempting to assess the significance of his constructions gains due emphasis.

As we might remember, Norris Kelly Smith addressed the same detail (the corretti) as follows:

"The "secret chapels" are not relevant to the nature of the building, for it contains no galleries or other kinds of wall articulation; they prompt us rather to think about the meaning of the building as a symbol of the Church, wose nature is exemplified not in hierarchical offices and dogmatic formulations but in the lives and deeds of people like ourselves -- only the coreti remind us that we too must imaginatively and personally participate in that larger order of things that constitutes the vital reality of the Christian Church, a reality for which the Church-as-institution serves only as an articulating enframement"

While it seems to me that the arched ceilings of those illusionary chapels provide an upward thrust that energizes the scenes above them, while the emptiness of their space emphasizes the heaviness and volume of the figures.

Apart from the ‘Annunciation’, the only scenes with large buildings shown in a foreshortened frontal setting are ‘The Annunciation to St. Anne’ and ‘The Birth of the Virgin’ in the uppermost row of frescoes running round the two main walls. It is exactly the same building which appears in both these frescoes, since throughout his work in the Arena Chapel Giotto carefully maintains the unity of place. It is, therefore, no exaggeration to say that the foreshortened frontal scheme is very rare indeed. The extreme oblique construction is also far less common than it was before. It likewise only appears at all amongst the scenes in the topmost row on either wall, so that it is once more seen side by side with the foreshortened frontal setting.

‘The Refusal of Joachim’s Offering’, the opening fresco of the cycle, shows the extreme oblique construction at its most aggressive. The architectural mass is solidly constructed, although the receding lines in several places tend to diverge, instead of running parallel to each other or converging. Seen from a normal viewpoint, emphasizing its solidity, the building is as full of jutting angles as possible. Everything advances and recedes, and nothing is in harmony with the plane. Yet at the potential point of greatest conflict the thrusting knife-edge of the figure platform is suddenly blunted, as if sheared off by the flat surface of the wall just as it was about to burst beyond the confines of the marble frame. This shows, perhaps, that Giotto was himself aware of the element of conflict in this type of composition.

Speaking of conflict, does the architecture enhance the psychological conflict in this event, or not?

Why isn't White asking that kind question?

Wasn't that issue more important, both to Giotto and Scrovegno,

as well as to the subsequent centuries that preserved it?

It seems that each straight line, as it converges or diverges from others, is responding to a dramatic rather than technical situation.

And it is neat how the corner of the platform feels like its been sheared off by the picture plane.

‘The Presentation of the Virgin’ seems to confirm the supposition. Its architecture is again set at forty-five degrees to the plane, and this time figures intervene to subdue the conflict. On the right, where the architecture juts most fiercely forwards, half the receding lines are covered by two onlookers, who face inwards, holding back the forward thrust and softening the hard edge of the block. On the left, the figures, climbing the steps and standing on the ground behind them, stop the plunge on into depth along the main lines of recession. The oblique construction of the architecture shows no sign of compromise. Yet the resulting wedge shaped mass is not allowed to burst the wall asunder.

Do the "figures intervene to subdue the conflict" (resulting from the architecture set at 45 degrees) ?

Or -- do the angles and planes of the architecture help establish the drama of the situation. (the young Virgin entering the world of adulthood) ?

The next three frescoes are equally valuable in helping to chart the direction in which the artist’s mind is moving. These scenes of ‘The Wooers Bringing the Rods to the Temple’, ‘The Wooers’ Praying’, and finally ‘The Marriage of the Virgin’ each contain a repetition of a building which is peculiarly interesting in construction.

At first glance the temple in ‘The Wooers Praying’ seems to be a normally constructed ‘interior’ seen from straight ahead. A closer look shows that the roof, and in particular its forward edge, slopes very slightly downwards to the left, whilst the altar-front runs softly, but quite definitely upwards in the same direction. Moreover, the receding lines of the coffered ceiling run with a considerable bias to the right, instead of evenly towards the centre, whilst the two inner walls clearly reveal a similar distinction. The left-hand wall is demonstrably less foreshortened than that on the right. Its forward edge all but encloses the small subsidiary semi-dome, the counterpart of which upon the other side is almost evenly cut in two. All these small distinctions lead to one conclusion. The seemingly frontal surfaces of the building are, in fact, softly, but quite consistently receding to the left, as if away from an observer standing a little to the right of its centre line. The construction is coherent in itself. Its repetition in the scenes on either side precludes the possibility that these slight variations are due to accident and not intention. The buildings are, all three of them, not frontal, but oblique.

I remember being thrilled by this series 40 years ago when I saw it in Padua, and the mystery of it still excites me. That little chapel is some kind of holy place and the priest is some kind of magician.

Looking at the reproductions before reading White's text, I was looking for differences between the chapels in the three paintings. The coffering in the ceiling is a bit more pronounced in the middle scene, but that's about all I could find.

And I certainly didn't notice that the top and bottom edges are not parallel, the frontal plane recedes softly to the left, and the viewer is sited a little to the right of center.

So I appreciate the subtlety of White's observation on that feature.

But did Giotto arrange it this way because he considered the oblique to be more progressive than the frontal?

Or was that off-kilter arrangement done to enhance that sense of mystery which I have felt so strongly?

The same minimal recession of surfaces which seem to lie completely in the wall plane also appears in the balcony seen in ‘The Wedding Procession of the Virgin’. This time it is an apparently foreshortened frontal building which turns out to be obliquely set.

Since we can clearly see that receding right wall, how could that ever be "an apparently foreshortened frontal building"?

And doesn't the anomaly of that enormous leaf overwhelm whatever sense of space is created by the building behind it?

Between the two poles of the very sharp and of the very soft oblique constructions lies the middle way adopted by Giotto in the fresco of ‘The Golden Gate’. In this scene an architectural composition of the first importance is experimented with, only to be developed in a very different manner in the subsequent fresco of ‘The Presentation of the Virgin’ , which has. already been considered in some aspects.

The composition of both scenes is similar in essence to that of ‘The Mourning of the Clares’ in S. Francesco at Assisi. There, however, both the faces of the church recede quite steeply, and its disposition as a whole stands in contrast to the firm horizontal of the bier, which lies parallel to the fresco surface. This slight weakness of connection in the parts is gone. At Padua the two elements of the composition are finely co-ordinated in both scenes. In both, the figures move convincingly over the bridge, or up the steps, at right angles to the main architectural mass. There is nothing to confuse the clarity of space or motion. Beyond these basic similarities of composition the two Paduan frescoes differ fairly widely. The recession of the main face of the architecture in ‘The Meeting at the Golden Gate’ is softer than in either of the other scenes. The continuous vertical of the right-hand tower, which forms the principal spatial accent, is so close to the border that long lines running downwards to the right, like those in the upper part of the Assisi fresco, are avoided. No devices are required, as in ‘The Presentation of the Virgin’, to soften a too strongly thrusting spatial block. The association with the surface accent of the frame is close enough to render them unnecessary. At the same time the fact that ‘The Meeting at the Golden Gate’ lacks the complexity of jutting shapes, which characterize both ‘The Presentation of the Virgin’ and the opening fresco of ‘The Refusal of Joachim’s Offering’ , gives it a correspondingly calmer spatial quality.

Comparing the the disposition of the buildings represented in those two paintings from Assisi and Padua, yes, they may be essentially similar.

But their roles in the composition are quite different.

In the "Mourning of the Clares", the facade is like a weeping face, with the mourning Clares flowing out, like tears, from the doorways. In the "Meeting at the Golden Gate", the twin towers buttress the two figures who are meeting between them to kiss.

And what does White mean by "slight weakness of connection in the parts" of the Assisi painting? Does this refer to whether the architecture appears to be solid -- or is White introducing a discussion of aesthetic quality (i.e., whether the design seems strong or weak)?

It is worthwhile to pause at this point, and take stock. So far only those frescoes, containing the prologue to the life of Christ, which occupy the upper row on the side walls and on the linking choir arch, have been considered. Within these limits Giotto’s architectural compositions can be divided into four main groups.

The first is made up of foreshortened frontal compositions. In these the earliest method of creating space whilst stressing the flat surface is still used.

The second is composed of the extreme oblique constructions. These also appeared alongside the earlier foreshortened frontal type at Rome and at Assisi, marking a new departure, a new emphasis on realism. At Padua, however, there are indications that the inherent compositional conflict, which grows step by step with the increasingly successful counterfeiting of solidity, has become something of a problem to the artist.

The third group is that in which it seems as if the artist wishes to retain the surface-stressing harmony of a frontal setting without entirely sacrificing the realistic connotations of the oblique construction. The outcome is a make-believe foreshortened frontal, a minimal oblique setting, which has the formal qualities of the first group, yet recognizes the conception of the realities of vision which is the basis of the second. The extreme delicacy of the four times repeated construction, noticed only by a minute fraction of the thousands who pass through the chapel, is alone strong confirmation that Giotto was himself actually conscious of both the formal and the realistic qualities of the new perspective patterns.

I was certainly one of those many thousands who didn't recognize the minimal oblique setting -- but I bet that I wasn't the only one who was thrilled by the sense of mystery that it created.

And what is the "inherent compositional conflict"?. Harmony need not be "surface stressing".

White has taken the leap from categorizing architectural presentations to making assertions about the compositional intentions of the artist without including any discussion of the narrative being presented.

That is the fundamental weakness of his argument.

Finally, in the single fresco of ‘The Meeting at the Golden Gate’ the artist makes use of a moderate oblique construction. This becomes the basis of the system used throughout the remaining frescoes of the chapel for all buildings seen from the outside.

The new compromise, which represents a genuine middle ground in the tug of war between the demands of realism and of surface pattern, is well represented by ‘The Last Supper’. This not only becomes a standard pattern in the scenes from ‘The Life of Christ’ in the lower registers at Padua, but is still used for the later work in the Peruzzi Chapel of Sta. Croce which marks the peak of Giotto’s achievement in those frescoes that survive.

The essential features of ‘The Last Supper’ , which are so often repeated both by Giotto and his followers, are twofold. In the first place there is no ambiguity; no doubt that the whole building is obliquely set. The downslope of the roof-ridge and the gutterboard, and the upwards recession of the bench on which the figures sit, backs turned to the beholder, are as clear as they are gentle. In the second, the building is now brought into the closest possible association with the surface of the wall, to which it is so nearly parallel, that is compatible with clarity.

The same desire for spatial realism in harmony with the flat surface, which seems to underlie the growth of a clear preference for architecture set obliquely in the picture space just at the moment when the formally aggressive tendencies of such a setting were being smoothed away, leads Giotto, at the same time, to important modifications in the structure of interiors.

Norris Kelly Smith noted that:

"..for even Giotto had not been able to infuse that quasi-liturgical subject with the kind of narrational intensity that distinguishes most of his Paduan frescoes. It is the most inert of all his compositions"

While I've noted that curious, but realistic, phenomenon of the disappearing foremost pillar, and that the P.O.V. is outside the chamber.

In the fresco of ‘Christ Teaching in the Temple’ the internal spaciousness is greater than in any of its precursors. There is abundant head room for the figures, and the outer limits of the sides and ceiling of the main space only just remain within the borders of the fresco frame. The latter actually cuts short the vaulted side aisles that appear to left and right beyond the arches closing in the central room.

The scene is an exceptional achievement even for Giotto. It is seen from a position slightly to the right of its mathematical centre, in conformity with the placing of the most important figure, that of the young Christ. The firm arc of seated priests and elders curving back into the space, carves out the reality of enclosure and defines it in a single movement. Nothing more is needed. Overhead, across the whole top of the scene, are hung two green festoons. They lie in the most forward plane, caught at the ends and centre of the foremost edge of the ceiling. The swinging curves, living completely in the plane, are echoed by the hanging top line of the arches running into depth. The very architecture of the room’s space mediates between these green catenaries upon the surface and the spatial figure curve which it encloses. This interplay of pattern on the surface and in space grows more exciting still when it is seen that the festoon upon the left hangs right across the principal three-dimensional join, where ceiling, back, and side walls meet. It is completely hidden. The same thing happens on the other side, and although the crucial point is lost beneath an area of damage,a continuation of the lines of wall and ceiling shows that the small, lost part of the festoon would have completely masked the spatial accent. The rectilinear coffered ceiling has its purpose in the definition of the architectural structure, but it is not allowed to add a harsh, unwanted emphasis to the sufficiently emphatic space created by the figures and by the softer double curve of arches. Instead a purely surface accent softens the spatial pattern of the ceiling, and ties the whole design together. The interplay, and actual visual equation, of curves lying on the surface and curves set in space lead to a full appreciation of their dual function as essential elements both in the three-dimensional realism, which gives immediacy to the story, and in the creation of the decorative pattern which transmutes the dead face of the wall into a living thing of beauty.

Those green festoons also echo the arms of young Jesus, and both the arms, festoons,

and the child savior's arguments all share a certain light, almost playful quality, and the festoons, like the arguments, have gone right over the heads of the audience.

BTW, when White declares that Giotto's reconciliation of spatial illusion with surface pattern is an "exceptional achievement", he sounds more like a critic of his contemporary 20th C. abstract painting, than an historian of the early Renaissance.

The scene of ‘Christ Before the High Priests’ shows the achievement of essentially the same result by opposite means. The space enclosed is principally defined by the repeated, unbroken orthogonals of the ceiling beams. As compensation, the figures are aligned much more across the surface than in the previous scene. A different device is this time used to stress the unity of space and plane. The central moulding, which runs across the back wall just below the windows, then turns round both corners and runs forwards on the side walls to enclose the entire spatial content of the room. This cornice, stressed by a colour change, is almost a single, mathematically straight line. Potentially a major spatial accent, it is used to emphasize the surface qualities of the design. In addition, it gives formal being to the dramatic unity and tension of the scene. It becomes a bar linking the heads to, gether in its grip, vibrating under strain.

These ambivalent elements in Giotto’s designs are distinguished from the occasional, chance occurrences of similar features in the work of other artists by their consistent use, their compositional prominence, and their close association with emphatic space. It is the strongly three-dimensional quality of the compositions in which they play an important part that gives them their particular significance.

Is the enclosed space "principally defined by the repeated, unbroken orthogonals of the ceiling beams" ?

Above, I've removed those beams, and the space of the room beneath them doesn't feel any different to me.

As an area of great interest that stops the eye, doesn't facial expression also affect how we read space?

And the interaction of facial expressions seems to be the main event in this scene.

The space of this room seems to be defined by two vertical, triangular wedges.

On left, the forward edge is the figure of Christ; while the forward corner of the priest's knee and platform is the forward edge on the right.

Another fine variant of this newly evolved compositional method is ‘The Wedding Feast at Cana’ . The depth is very calmly indicated by the L-shaped table, since its angle is filled in, masked by the figures, whilst a line of wine jars lies across the surface on the right. The canopy that crowns the walls reiterates the spatial content of the scene, although here again the effect is modified. The finials and the ornamental vase, which decorate the upper edge, are made to form a constant link between the architectural design in depth and the flat band that frames the scene. Between these areas of controlled spatial definition above and below, the fresco is divided horizontally at the top of the striped wallhanging. The sharpness of the colour contrast makes this demarcation line a striking feature of the composition. Once again it is a case of emphasized ambivalence. The line, which as before encloses the whole room space, turning through a right angle at each corner of the wall, s shown as being practically straight, repeating the near horizontal disposition of the heads below. The slight depression in the wings, almost invisible in reproduction, is, however, balanced by the soft, but noticeable upturn of the diaper moulding higher on the wall. This forms a visual transition to the firmly space defining angles which distinguish the orthogonals and transversals of the ceiling canopy.

One might also notice that the POV is right of center, closer to the Virgin, while the bride is in the center of the scene -- making for a nice contrast between who's important and who's really important.

There's a gentle humor about this scene, as the big round shapes of the wine jars are echoed by the groom's belly, and Christ is explaining something to an attentive young woman on the left.

The mention of the transversals of the ceiling canopy leads to an interesting and historically important point. The banqueting hail definitely appears to be rectangular in plan. The two sections of the L’shaped table are parallel to the walls, and it seems reasonable to suppose that these arms are set at right angles in the normal way. The canopy above is so disposed, however, that the forward edges of the wings are shown receding softly downwards to the left and right. In the ‘Christ Before the High Priests’ it is noticeable that the throne is set obliquely, whilst its back shows that it is conceived as running parallel to the side wall, if not actually attached to it. The same phenomenon is visible in the ‘The Approval of the Rule’ at Assisi and occurs quite frequently both there and elsewhere. The ceiling canopy of ‘The Feast at Cana’ is, however, the first clear-cut example of this tendency to apply to architectural details the rules of natural vision based upon the turning of eye and head to look directly at the various separate objects in the field of vision. There is no other case of it in Giotto’s extant work. But when the story is continued in the paintings of Giotto’s followers, this detail will emerge as the first signal of a long, significant, and historically important development. It is a tentative beginning, and in itself may, or may not be a deliberate experiment. About the subsequent growth of the idea there can be no doubt.

I can feel this head turning to see the architecture in this painting, but it also seems to be the case with the two canopies on either side of the Joachim expelled from the Temple.

The foregoing analyses of Giotto’s Paduan frescoes fall into a definite pattern. If they are individually correct, and are, which is even more important, truly representative of the forty or so required for complete coverage, the pattern will help to build up the larger picture both of Giotto’s own life’s work and of the history of art in Italy as a whole. In doing this it will confirm the validity of its own line of growth.

The general configuration in Giotto’s case is that of a steadily increasing harmony between. the flat wall and an ever more ambitious spatial realism. This pattern is supported by the presence of a similar concern in the arrangement of the figure design. It has often been remarked that the position of the figures on the surface in relation to each other and to the compositional diagonals and other lines and subdivisions, which express the inherent geometrical properties of the pictorial rectangle, is as important as their individual solidity and their interaction across convincingly described pic tonal space. The trend of Giotto’s ideas is equally stressed by the flat marbling and low relief of the architectural framework, which combines with the reality of the wall in a way that is entirely new. Realism is intensified, and at the same time an attempt is made to avoid the destruction of those qualities which the less realistic decorative art of earlier centuries possessed in such abundance.

This pattern of development reflects the fact, confirmed by recent technical investigations, that work in the Arena Chapel was started at the top and steadily continued downwards. This was the usual course, for purely practical reasons, and the non-existence of cartoons in the fourteenth century makes it unlikely that the order of conception was reversed in execution. Finally there is the fact that the perspective constructions grow increasingly consistent as the lower registers are reached.

Here's a painting from Assisi.

Is there any painting in the Arena Chapel that shows greater "harmony between the flat wall and an ever more ambitious spatial realism."?

‘When all these observations are considered in relation to the later frescoes of the Bardi and Peruzzi Chapels it becomes clear that the direction of development at Padua cannot be reversed.

The history of the emergence of the oblique construction in the final quarter of the thirteenth century, and the characteristics of the artists using it, led to the conclusion that its basis lay in natural observation. The fact that it later comes to be the standard pattern used by Giotto seems to increase the validity of this conclusion. The oblique construction is, indeed, used by him in fully seventy-five per cent of the architectural compositions at Padua. That is to say, three times as often as all other settings put together. In his approach to narrative and to the human figure Giotto concentrates all his attention upon fundamentals. The probability is, therefore, very strong that this predominance of one particular spatial pattern is not a mere coincidence. It is rather a reflection of his passionate interest in reality as a foundation for the ideally ordered world that is his art.

The close connection of the two phenomena is witnessed by the singular lack of pattern prototypes available to the artists who espoused the new construction. It is not a question of the increasing use of an already common pattern. Amongst the hundred or so Italian panels painted before 1300 in which architecture appears, there are no examples of a normally seen oblique construction.

Here's an architectural detail from Cavallini in 1291.

(to which White recently referred)

Isn't this a "normally seen oblique construction."

And how would White distinguish between the "normally seen"

from any other way of seeing?

This is the first time that the notion of "normal" seeing

has entered his discussion.

And how did "The history of the emergence of the oblique construction in the final quarter of the thirteenth century, and the characteristics of the artists using it" lead us to "the conclusion that its basis lay in natural observation." ?

Might there be any other reason for the use of the oblique construction ?

One might also notice that Giotto's figures have a greater sense of weight and volume than can be found in the work of his predecessors. This gives them a different, more earthy dramatic quality. Wasn't the oblique construction of the architecture a more consistent setting for the figures he would place within them?

And is it only a coincidence that his more earthy figures make their first appearance in the home church of the down-to-earth Franciscans?

In discussing the work of the great late thirteenth and early fourteenth century artists the conflict with the plane surface, which emerges as the component parts of the pictorial world take on increased solidity, has been treated as a problem not merely in retrospect, but as one which existed for the artists themselves. At Assisi the balance was restored by an extension of traditional ways of building up a decorative surface pattern. At Padua the manipulation of perspective itself was the means by which the troubles which resulted from its use were remedied. It is always difficult, however, to make the jump from the visible records of achievement to the sometimes conscious, and often unconscious mental processes behind them. There is always the danger that the mental process belongs to the modern analyst, and not to the long dead artist. It may, consequently, prove revealing to move for a moment right outside the stream of Western art.

White's concluding remarks about the different solutions at Assisi and Padua to the "problem" are not supported by the previous text.

But nobody can dispute that "It is always difficult to make the jump from the visible records of achievement to the sometimes conscious, and often unconscious mental processes behind them".--- especially since White is prone use the language of mid-20th century art criticism to discuss paintings made 700 years earlier.

It is generally agreed that in Islamic, and in Chinese art the decorative surface is of paramount importance throughout all the periods of highest and most characteristic achievement. That is, until the imitation of western models finally changed the direction of the traditional currents. In both arts the representation of certain aspects of the natural world is nevertheless carried to dazzling perfection. The formal problem, if it is not simply a contemporary one, should therefore be reflected in these arts, and the solutions found may throw some light upon the history of art in Italy from the late thirteenth century onwards.

Unfortunately, White begins his discussion of Islamic and Chinese painting with two problematic assumptions and he is not going to offer us any examples.

Fan K'uan ,Sung Dynasty

Jacob Isaackszon van RUISDAEL

Is the "decorative surface" really more prominent in the Sung painting than in the Dutch Baroque? If so, I have no idea what that phrase might mean.

Tale of Genji, Early 17th C., Japan

In Islamic miniatures the surface stress is positive. Flat areas of brilliant colour are left sometimes unadorned, and sometimes sprinkled evenly with delicate designs of flowers or with the carpet-makers’ geometric patterns. The gorgeous butterfly designs of text and illustrations are the formal outlet for that same burning directness which is characteristic of the Mohammedan religion and of so many of its middle eastern variants and forerunners.

In Chinese art, on the other hand, the surface emphasis is negative rather than positive. It is in close accordance with the calm acceptance, the contemplative natural mysticism, which reached its highest flowering in Taoism. The surface is left undisturbed. Colours are few, and soft. Ink, and delicate monotone washes are the characteristic media. Spiritual and decorative qualities are valued high above imitative naturalism, the evocative above the representational. Art stops short long before the plane can be disrupted by geometric space or obtrusive solids. The unmarked silk, or paper, is at once the atmosphere, the space, and the inviolate decorative surface. Only in certain Buddhist works such as the great series of paintings in the distant caves of Tun Huang, which depend, with Indian mediation, upon patterns which originated in the Hellenistic world; only in these relatively few examples is there any radical departure from the general rule.

Poles apart as Chinese and Islamic art may be in many ways, they are alike in carefully eschewing just those patterns which, it has been suggested, are spatially the most aggressive of those used in western art. The box interior, with its too insistent recession of floor, ceiling, and side walls, is avoided equally by both.

I've offered an example of a Japanese screen as a "positive" surface that is much closer to Chinese than Islamic culture.

Also, it offers something of a box, although it's one that is seen from above rather than from within.

But I won't respond to White's brief discussion of Asian art any further.

He introduced it so that he might claim that his "problem" of spatial realism versus surface design was universal -- but I still have no idea what that problem might be.

Every mark that is placed upon a surface needs to be incorporated within a design if the finished piece is going look good -- and nothing, other perhaps than a square of flat, even color, is without some illusion of space.

No comments:

Post a Comment