One of 19 essays in the catalog of "Abstract Art : Abstract Painting 1890-1985" ..for the 1986 exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

**********

Paul Serusier, Talisman , 1888, 10 x 8 "

Robert Welsh, the author of this catalog essay, does not mention this piece,

but I’ve put it at the beginning of this post because I like it.

It’s almost abstract - and Welsh does mention some other pieces by this artist.

The painting appears to have begun as a view of autumn trees beside a pond that reflects them. But then other areas are added that make sense as a painting but not as a landscape. That kind of back-and-forth is more common now than then.

Regretfully, there were no other abstract, or near abstract paintings by Paul Serusier that I could find.

Paul Serusier, Blind Force, 1892, 36 x 28"

Walsh’s essay, like the above painting that he shows, really does not belong in the catalog of an exhibition of abstract painting.

It's primarily about the symbols used by the Nabis - a group of figurative artists.

Yes - many of their symbols are geometric - but no, a painting with clearly identifiable human figures is not abstract art. (Unless all paintings are)

The author does tell us that the above Serusier piece "without its single figure would be as abstract as the solar disks of Robert Delaunay and Frantisek Kupka" (which is, BTW, the only mention of the abstract work of either of those two artists)

But then we might also say that without that brief mention, this essay would have nothing to do with abstract painting. It does not appear that notable French abstract painters were much involved with Theosophy, Anthroposophy, or any other kind of spiritualism trending at that time among the cultural elite. And even the Nabis and Symbolists are connected by the thinnest of threads:

Gauguin’s documented awareness during his year spent in the South Pacific of such encyclopedic studies of universal religious systems as JA Moerenhout Voyages aux iles de grand ocean (1837) and Masseys, A book of the beginnings, is less indicative that he had accepted the basic tenets of modern theosophy than that he shared in the belief that all religions, including down at the Polynesian Maori people’s participated in a common metaphysical dualism between the realms of heaven and earth.

Paul Ranson, Witches around a Fire, 1891, 14 x 21"

It’s not abstract - and nor would I call it a great painting.

But Welsh shows it —- it’s a lot of fun with three naughty nude babes in the forest -

and as Welsh might note - it would be abstract except for so many figures.

Here are the Delaunay and Kupka shown and mentioned:

Frantisek Kupka, Disks of Newton, 1910-11

Paul Delaunay, Circular Forms, 1912, 28 x 42"

Both feel cosmic in scope

and might well depict the birth, original or ongoing, of our 13.7 billion year old universe.

Is that a spiritual theme?

I think so - even if it is unconnected to any specific faith or cult or metaphysical discipline.

It confronts/expresses the infinite - which might be one definition of spiritual.

*********

Maurice Denis, Catholic Mystery, 1889, 38 x 56"

Welsh also shows us this surprising conflation of the Immaculate Conception

with the daily devotion of a young cleric and his well behaved altar boys.

One website identifies the cleric as the deacon who presents an open Bible to the priest during the Mass.

Such a hush of silence

Such a glow of illumination.

Such a tasty interaction of cool whites with flashes of brilliant red.

And what about that expression on the face of the Virgin.

Both loving and severe,

like a young mother who won’t be taking any more nonsense from her boys.

Look at that stare! She can see right through them.

The older male behind them responds by closing his eyes.

If it weren’t for the liturgical robes and halos, this could be older brother who has caught his two younger siblings stealing sugar from the pantry and now presents the contrite youngsters to mother.

In other words - there is an emotional reality of family life about this scene.

Maurice Denis, Way to Calvary, 1889, 16 x 12

Another masterpiece from the teenage artist - and again contemporary church workers are interacting with divinity - though this time, their heartfelt devotion is palpable.

In the art of the fervently Roman Catholic Maurice Denis the use of geometric signs remains within a distinctly Christian context, but the means of utilization are by no means traditional. Hence the positioning and truncation of the cross in The Way to Calvary, 1889, renders it readable as both a Latin and a Saint Andrew's cross, the X form of which defines a set of triangles, and it may not be incidental that the number of female followers present is seven. Blavatsky explained the X cross as pointing to the four cardinal points, hence infinity, and as indicating the presence of God in humanity, ideas that, if known to Denis, might not have seemed inimical to his Christian faith. In the three finished versions of Denis's Catholic Mystery, from the years

1889-91 (see, for example, above), cross forms are present not as a necessary part of the annunciation theme but as defined by the window mullions, their dematerialized shadows on the curtains at left and right, and the design on the sleeve of the figure at left. This figure is not a winged archangel but an officiating priest accompanied by two altarboys.

The priest (and the boys in one version) is depicted with a halo conforming to no orthodox representation of a scene from the life of the Holy Virgin. These iconographic liberties combine to suggest that the geometric figures of the cross and circle (according to esoteric doctrine each in its own way is indicative of immortality are as essential to understanding this Catholic mystery as the narrative scene.

In similar fashion various forms of crosses, sometimes ringed with circles, so frequently appear in Denis's woodcut and lithographic illustrations (made in the 18gos but only published in 1911) for Paul Verlaine's poem cycle Sagesse that they assume a symbolic identity in whole or in part independent of any imaginable narrative meaning.

Welsh’ s essay considers these paintings only as places where certain geometric symbols may be found - and makes no other link to spirituality. How sad - though well within the parameters of this catalog - as well as the discipline of art history as now practiced.

Christian themes are anathema to a rigorously secular narrative of Modern Art.

Maurice Denis, The Mass, 1890

Priest as magician - standing between the natural world of the altar boy in the foreground and the supernatural in the background.

Is he sanctifying the host? As a non-Catholic, that’s my best guess. A critical biography of the artist might answer that question - or an academic paper on JSTOR - but I’ve yet to locate one online. Welsh offers his best guess below:

In a painting of the same period known as The Mass, circa 1890 , Denis depicts a priest who wears a Tobe with a large cross, at the intersection of which is placed an oval. The priest looks and gestures toward a yellow disk suspended in front of an altar. With no further indication provided as to the liturgical significance of the act being depicted, independent of any narrative context, the viewer is left to ponder the ultimate mystical meaning of the cross and circle for Christianity specifically. One may not presume that Denis viewed Christian symbols as merely a single expression of esoterically uncovered truths common to all world religions. Yet his close association with Sérusier and other occult-inclined Nabis makes it unthinkable that he would have remained unaware of such doctrines. It might be safest to suppose that he simply accepted the syncretic view of the origins and cosmologies of the ancient religions that preceded Christianity while believing that the latter had superseded the others by the depth of its mystical teachings.

Though he does not belong in an exhibition of abstract painting , Maurice Denis, while still not yet twenty, wrote his very famous epigram : Remember that a picture - before it becomes a battle-horse, a nude woman or any sort of anecdote - is essentially a flat surface covered by colours arranged in a certain order.

That the flat surface may indeed characterize Modern painting - this assertion is the first sentence of an essay he called "A Definition of Neo-Traditionalism" (1890)

An English translation can be found online on

Peter Brooke's website. BTW - Brooke has plenty of material on that site that is quite relevant to spirituality in French painting at the end of the 19th Century. He’s a painter himself , and a serious scholar of Albert Gleizes and colleagues, but he does not appear to be associated with any university. You might call him an independent thinker. His website offers a fine discussion of the issue of subject versus object as raised among certain artists of that period. Subject concerns the details of identifiable narrative - object concerns the physicality of the piece itself.

Charles Filiger (1863-1928), Chromatic Notations, 1886, watercolor

Welsh shows us this kind of nearly abstract work - and it does nothing for me - at least in this reproduction. Looks like the design of a playing card or board game.

The apparent mixture of Christianity and geometry in the art of Filiger is even more difficult to unravel than in the case of Denis. In large part this is due to the habits (not the least of which was his failure to date his oeuvre) of this unfortunately obscure artist, whose career, apart from difficulties due to homosexuality and alcoholism, did not produce a clear record of artistic development. Nonetheless he represents the best example of an artist with established connections with Gauguin

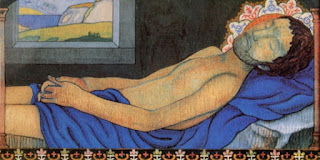

Charles Filiger, Recumbent Christ, 1895

But this piece (which Welsh does not show) is worth puzzling over.

Christ does not appear to be dead -

but has He ever been been depicted otherwise when recumbent?

(Other than on a storm tossed ship on the Sea of Galilee)

I wonder whether the title is accurate?

William Bouguereau, Pieta, 1876, 88 x 59

Here’s a contemporary depiction of Mary and Jesus where the expressions are more theatrical. It’s quite melodramatic - but then is quieted by the calm, heavy, tableware in the foreground.

The artist was also known to be a devout Roman Catholic.

It’s a fine example of what Maurice Denis called "the triumph of academic convention, of pathos-filled trompe l'oeil, of a naturalism at once theatrical and pietistic." Which is not necessarily a negative criticism. Demis asserted that every depiction of Nature follows one convention or another .

Albert Gleizes (1881-1953) untitled 1921

Albert Gleizes, Brooklyn Bridge, 1915

An abstract painting despite its title,

without which no bridge would ever come to mind.

But it certainly has the thrill and power of a great American city.

Gleizes was into art theory, not spirituality, so I guess that’s why he was not included in this catalog. I can’t stand his analytic Cubism - or what he did in his final decades. But what he did around 1920 - wow!

Eventually, I’d like to append many more early Modern French abstract painters to this post. Maybe I’ll even find one who followed Madame Blavatsky.

No comments:

Post a Comment