Maurice Tuchman : Hidden Meanings in Abstract Art

The first of 19 essays in the catalog of "Abstract Art : Abstract Painting 1890-1985"

for the 1986 exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art as curated by the author of this essay.

***************

Jasper Johns, Book, encaustic and book on wood, 9 x 13"

Abstract art remains misunderstood by the majority of the viewing public. Most people, in fact, consider it

meaningless. Yet around 1910, when groups of artists moved away from representational art toward abstraction, preferring symbolic color to natural color, signs to perceived reality, ideas to direct observation, there was never an outright dismissal of meaning.

Instead, artists made an effort to draw upon deeper and more varied levels of meaning, the most pervasive of which was that of the spiritual.

Friedrich von Schlegel wrote, "A philosophical work must have a definite geometrical form. The 1794 publication of Charles F.

Dupuis's Origine de tous les cultes ou religion universelle, replete with cabalistic and other occult texts, underscored this interest.

Three paintings from a remarkable series of geometric paintings made about 1910 by Paul Sérusier convey essential implications of the geometric-occult nexus. Caroline Boyle-Turner has recently shown that Sérusier hoped to restore forgotten rules based on geometry to a religious art that would be accessible to a wide audience. Sérusier derived most of his ideas from Desiderius Lenz, the German monk and theorist, with whom he stayed at the monastery of Beuron, and from Pythagoras and Plato; Plato's Timaeus provided the artist with an explanation of the pyramid as the origin of all other forms and provoked The Origins, circa 1910 .

Boyle-Turner believes that Sérusier planned and may have executed a large series of geometric shapes, intending "to illustrate the basic geometric shapes available to any artist, which should form the base of all of the forms on the canvas . . . (and that] an artist should begin a painting with compass and ruler." At the heart of Sérusier's insistence on basic geometric shapes was the idea that art must depict the fixed and unchangeable. These shapes, described in the theosophical terms he learned from Édouard Schuré's Les Grands Initiés:

Esquisse de l'histoire secrète des religions, were the

"building blocks to all other forms, particularly the human figure. By using these simple

'correct shapes in correct proportional relationships, the painter could achieve what Sérusier called 'equilibrium.' This equilibrium would be felt by anyone contemplating the work, since the shapes, angles and proportions were universally understood by sensitive people, no matter what culture or time period.

Terms such as occultism or mysticism should be defined carefully because of the association with the ineffable that surrounds these words and because they are context-specific: art historians and artists use these terms differently than do theologians or sociologists. In the present context mysticism refers to the search for the state of oneness with ultimate reality. Occultism depends upon secret, concealed phenomena that are accessible only to those who have been appropriately initiated. The occult is mysterious and is not readily available to ordinary understanding or scientific reason.

Several ideas are common to most mystical and occult world views: the universe is a single, living substance; mind and matter also are one; all things evolve in dialectical opposition, thus the universe comprises paired opposites (male-female, light-dark, vertical-horizontal, positive-negative); everything corresponds in a universal analogy, with things above as they are below; imagination is real; and self-realization can come by illumination, accident, or an induced state: the epiphany is suggested by heat, fire, or light.

Spiritually inclined artists sought out others who shared their interests and studied diagrams and texts in original spiritual source material. William James contrasted "emo-tions of recognition" with "emotions of sur-prise" to explain the attraction of artists for kindred spirits of another era or medium. 32 In the present context, emotions of recognition allude to kinships that artists discovered as they formulated their own pictorial vocabu-lary. For example, Arthur Dove's Distraction, 1929 may be understood to be an abstraction of William Blake's The Body of Abel Found by Adam and Eve, circa 1826; Dove almost certainly examined a reproduction of the earlier work

the French artist Francis Picabia played a key role in transmitting synesthetic ideas to the American art world in the 1910s Picabia went further than other contemporary artists in America in his verbal affirmation that subject matter was of no value in an art that "expresses a spiritual state land] makes that state real by projecting on the canvas the finally analyzed means of producing that state in the observer. "

Picabia made his claim for the power of art not only by suggesting an analogy between painting and music but also by emphasizing that the rules of painting, no less than of music, had to be learned:

If we grasp without difficulty the meaning and the logic of a musical work it is because this work is based on the laws of harmony and composition of which we have either the acquired knowledge or the inherited knowledge. . . . The laws of this new convention have as yet been hardly formulated but they will become gradually more defined, just as musical laws have become more defined, and they will very rapidly become as understandable as were the objective representations of nature. "

Between 1907 and 1915 painters in Europe and the United States began to create completely abstract works of art. It is neither our intention nor our interest here to resolve the issue of who was the first abstract painter or what was the first abstract painting. Instead we are more concerned with how this abstraction evolved and, in particular, how four leading abstract pioneers - Wassily Kandinsky, Frantisek Kupka, Piet Mondrian, and Kazimir Malevich - moved toward abstraction through their involvement with spiritual issues and beliefs. An examination of their development, and that of the generation following them, reveals how spiritual ideas permeated the environment around abstract artists in the early twentieth century.

In 1912 Kandinsky assessed the work of Matisse, pointing to his search for the "divine" but criticizing his "particularly French" exaggeration of color, and the work of Picasso, which "arrives at the destruction of the material object by a logical path, not by dissolving it, but by breaking it up into its individual parts and scattering these parts in a construc tive fashion over the canvas. For Kandinsky these approaches represented two dangers in contemporary art: "On the right lies the completely abstract, wholly emancipated use of color in 'geometrical form (ornament); On the left, the more realistic use of color in 'corporeal' form (fantasy). "Kandinsky advocated a different role for the artist:

The artist must have something to say, for his task is not the mastery of form, but the suitability of that form to its content. . .. From which it is self-evident that the artist, as opposed to the nonartist, has a threefold responsibility: (1) he must render up again that talent which has been bestowed upon him; (2) his actions and thoughts and feelings, like those of every human being, constitute the spiritual atmosphere, in such a way that they purify or infect the spiritual air; and (3) these actions and thoughts and feelings are the material for his creations, which likewise play a part in constituting the spiritual atmosphere.

What a wonderful painting. Painted on glass to be viewed from the back, it feels other worldly.

For Kupka, as for the Theosophists, the essence of nature was manifested as a rhythmic geometric force. Consciousness of this force was made possible by disciplined effort as a medium; Kupka was a spiritualist throughout his life. He announced in 1910 that he was preparing to state publicly his beliefs in theosophical principles and spiritual-ism; his 1910-11 letters to the Czech poet Svatopluk Machar note his fascination with the supernatural world, spiritualism, and telepathy and his need to express abstract ideas abstractly. The First Step, 1909-13 is a painting whose imagery is rooted in astrology and pure abstraction. The painting may be interpreted as a diagram of the heavens and as a nonrepresentational, antidirectional image referring to infinity and evoking the belief that one's inner world is truly linked to the cosmos. Years earlier Kupka had written of a mystical experience in which "it seemed I was observing the earth from outside. I was in great empty space and saw the planets rolling quietly.

I construct lines and color combinations on a flat surface, in order to express general beauty with the utmost awareness. Nature (or, that which I see) inspires me, puts me, as with any painter, in an emotional state so that an urge comes about to make something, but I want to come as close as possible to the truth and abstract everything from that, until I reach the foundation (still just an external foundation!) of things… I believe it is possible that, through horizontal and vertical lines constructed with awareness, but not with calculation, led by high intuition, and brought to harmony and rhythm, these basic forms of beauty, supplemented if necessary by other direct lines or curves, can become a work of art, as strong as it is true

Art was a lifelong transformative pursuit for Lee Mullican. He painted The Ninnekah while he was a member of the short-lived Dynaton group in San Francisco. According to the artist, “What we were involved with was a kind of meditation, and for me this had to do with the study of nature, and the study of pattern, and the study of that sort of thing from which one could receive a meditative response.”

The present feeling seems to be that the artist is concerned with form, color and spatial arrangement. This objective approach to art reduces it to a kind of ornament. The whole attitude of abstract painting, for example, has been such that it has reduced painting to an ornamental art whereby the picture surface is broken up in geometrical fashion into a new kind of design-image. It is a decorative art built on a slogan of purism. (Barnett Newman, mid 1940’s)

To this approach Newman opposed his own intentions and those of Gottlieb, Rothko, Pollock, and others of the emerging New York School:

In the 196os, as earlier in the century, it was also possible to make abstract art without reference to spiritual matters. Diebenkorni's return to abstraction in 1966, when he moved to Los Angeles and began his Ocean Park series, is a capital example of resonant abstraction that does not hinge on spiritual content.

Frank Stella and Richard Diebenkorn are, among others, notable examples of artists who distinguished their artistic concerns from those presented in the exhibition The Spiritual in Art.

Diebenkorn responded sensitively to this issue, writing to me, 23

March 1985, after having read the prospectus for the exhibition:

Tuchman says a lot in this introductory paragraph - and he makes two assertions that are not necessarily compatible.

The first is that the artists who pioneered non-representational art were trying to connect to something outside their paintings - which he will later call a "spiritual system".

The second is that the above connection consisted of ideas associated with symbols.

Does he really believe that non-objective artists should "prefer symbolic color to natural color, signs to perceived reality, ideas to direct observation" ? I get that natural color and perceived reality is no longer an issue - but artists still might recognize and utilize the effect that certain kinds of shapes and colors have on the human imagination, with no symbols or verbal ideas involved at all.

We also might note that the title of this essay, "Hidden Meanings in Abstract Art", also suggests that visual experience alone is insufficient for the comprehension of intended meaning - even when recognizable objects and codified symbols are absent. Informed interpretation is required to reveal what has been hidden.

We should recognize here at the beginning of this essay, a postscript found at at the end. This is not so much a monograph by Tuchman about spirituality in abstract art as a transcription of 15 hours of him talking with his 28 year old associate curator, Judi Freeman, who then condensed and edited their conversation. We might call it brainstorming.

The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985 demonstrates that the genesis and development of abstract art were inextricably tied to spiritual ideas current in Europe in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. An astonishingly high proportion of visual artists working in the past one hundred years have been involved with these ideas and belief systems, and their art reflects a desire to express spiritual, utopian, or metaphysical ideals that cannot be expressed in traditional pictorial terms.

Our idea is not new. Modern art histories, beginning with Arthur Jerome Eddy's writings in 1914 and continuing in Sheldon Cheney's in the 1920s and 1930s, accurately reflected abstract artists' interest in expressing the spiritual. Eddy, writing at a time when purely abstract canvases were still virtually wet paint, identified as a contemporary artistic goal "the attainment of a higher stage in pure art; in this the remains of the practical desire are totally separated (abstracted). Pure art speaks from soul to soul, it is not dependent upon one use of objective and imitative forms. He concluded pithily: "It is only when new and strange forms are used because they are necessary to express a spiritual content that the result is a living work of art. The world reverberates; it is a cosmos of spiritually working human beings. The matter is living spirit."

In 1924 Cheney reviewed connections between abstract art and music. He recognized that much of the beautiful was produced "by the inner need, which springs from the soul" and wondered if "perhaps we shall find that such things speak to us as we grow more spiritual"; "the ideal of abstraction somehow seems to underlie the whole modern art movement." By 1934 Cheney was further attracted to mystical ideas, as evidenced by his book Expressionism in Art.4 In 1945 Cheney, now deeply and personally involved with mysticism, wrote a popular history of mystical thought, but in it his disdain for "modern painters who try to isolate a geometrical order in 'abstract pictures, or those who speak of revealing 'form' without serious regard to subject" reflected the new opposition in American society to the spiritual-abstract connection.

Our idea is not new. Modern art histories, beginning with Arthur Jerome Eddy's writings in 1914 and continuing in Sheldon Cheney's in the 1920s and 1930s, accurately reflected abstract artists' interest in expressing the spiritual. Eddy, writing at a time when purely abstract canvases were still virtually wet paint, identified as a contemporary artistic goal "the attainment of a higher stage in pure art; in this the remains of the practical desire are totally separated (abstracted). Pure art speaks from soul to soul, it is not dependent upon one use of objective and imitative forms. He concluded pithily: "It is only when new and strange forms are used because they are necessary to express a spiritual content that the result is a living work of art. The world reverberates; it is a cosmos of spiritually working human beings. The matter is living spirit."

Did Eddy ever develop "spirituality" into a system or ideal ? In the words quoted, he refers to "a spiritual content" rather than "the spiritual truth". He seems to share Kandinsky’s generic notion of spirituality as an inner need that goes forward and upward.

In 1924 Cheney reviewed connections between abstract art and music. He recognized that much of the beautiful was produced "by the inner need, which springs from the soul" and wondered if "perhaps we shall find that such things speak to us as we grow more spiritual"; "the ideal of abstraction somehow seems to underlie the whole modern art movement." By 1934 Cheney was further attracted to mystical ideas, as evidenced by his book Expressionism in Art.4 In 1945 Cheney, now deeply and personally involved with mysticism, wrote a popular history of mystical thought, but in it his disdain for "modern painters who try to isolate a geometrical order in 'abstract pictures, or those who speak of revealing 'form' without serious regard to subject" reflected the new opposition in American society to the spiritual-abstract connection.

In "The Story of Modern Art", Cheney categorized several early Modernists (Van Gogh, Picasso, Matisse, Klee) as "form seeking" - so presumably he might have called them "formalists". Cheney was a journalist with a background in theater - not a philosopher, poet, spiritualist, or art historian. We cannot expect his approach to be anything more than superficial.

No doubt the perception of a link between alternative belief systems and fascism made critics and historians in these decades reluctant to confront the spiritual associations of abstract art. To use the word spiritual in the late 19305 and 19405, as Richard Pousette-Dart recently acknowledged, was near-heresy and dangerous to an artist's career.? Intellectuals interested in modernist issues became more concerned with purely aesthetic issues. Alfred Barr, director of the Museum of Modern Art, was the outstanding example of an art historian turned aesthetician. In Cubism and Abstract Art (1936) he graphically charted artistic movements from 1890 to 1935. Although intertwined and somewhat complex, his chart showed each artistic movement as the logical outgrowth of the aesthetic concerns of preceding movements. Barr's views, which shaped the collection of the Museum of Modern Art and in turn helped New York become the focus of artistic activity in the United States during the second half of this century, encouraged the wave of formalist criticism dominating studies of modern art in the United States and influencing the popular view of modern art.

Barr mounted famous exhibitions of Van Gogh, Picasso, and Matisse (those "form seeking" artists mentioned by Cheney). Whom would Tuchman have preferred MOMA to exhibit ?

Tuchman has introduced the polarity of formalism vs. spirituality. But judging from the Jasper Johns piece he put at the beginning of his essay, a more relevant polarity might be visual versus conceptual. I’m doubting that Barr denied the spirituality of the pieces he selected - he just did not think of it as a relevant criteria.

Paul Serusier, Tetrahedons, 1910

Perhaps the actual piece feels different - but nothing like equilibrium ever crossed my mind over the first ten times I saw this image before ever reading the text. "Queasy" was more like it. The image feels so clinical - like an illustration of chemicals released into the blood stream by a cold medicine.

Helen Frankenthaler, 1958 , Hotel Cro-Magnon

(My pick)

Parthenon frieze, 438-432 BC

A "state of oneness with ultimate reality" is what I search for in visual art- and what I’ve found across time and continents - mimetic, non-objective, and everything in between. When the compelling parts of a painting can be experienced within a single spirit driven form, it’s analogous to a god created, purpose driven universe. So it’s something like a religious experience - like being enveloped within a chapel, or Malraux’s the museum without walls. Original concepts may be interesting, but visuality is a different kind of experience.

And so I find Serusier’s Tetrahedons intriguing - but it remains the illustration of a concept. While I find the above two examples to be transcendent and blissful. I hope others do not need to be "appropriately initiated" to experience them that way as well- but if they do, a school, church, or secret cult may not be necessary.

Several ideas are common to most mystical and occult world views: the universe is a single, living substance; mind and matter also are one; all things evolve in dialectical opposition, thus the universe comprises paired opposites (male-female, light-dark, vertical-horizontal, positive-negative); everything corresponds in a universal analogy, with things above as they are below; imagination is real; and self-realization can come by illumination, accident, or an induced state: the epiphany is suggested by heat, fire, or light.

One example would be Taoism — and daily training can be added to that list of paths to self-realization. An exhibition of Taoist art came to the Art Institute a few decades ago - and it was mostly disappointing - ie, its aesthetic level was no higher than what you would find in your nearest American parish church.

William Blake, The Body of Abel Found by Adam and Eve, 1826

1805-1809 version

(Both of the above have been horizontally flipped to better match the Dove)

Arthur Dove, Distraction, 1929

Tuchman offered no footnotes to reference this connection - and "almost certainly" tells us that this is his conjecture. Dove's flower reaching for the sun is way different from Blake's man being cursed. They do have some things in common, however, and both seem to have originated in a world of the spirit, rather than planet earth.

The five underlying impulses within the spiritual-abstract nexus: cosmic imagery, vibration, synesthesia, duality, sacred geometry - are in fact five structures that refer to underlying modes of thought. That they are common to a wide variety of artists, writers, and thinkers is reminiscent of a similar pattern present in the "spiritual families" of artists and eras identified by art historian Henri Focillon in The Life of Forms of Art (1948).

I wonder which impulses he would attribute to that Arthur Dove painting. Vibration ?

Francis Picabia, Ecclesiastic, 118 x 118", 1913

(My pick)

Picabia, Negro Song II, 25 x 27 ". Watercolor, 1913

(My selection)

I’ve seen Picabia’s large piece at the Art Institute many times. Maximum energy - minimum feeling - like ragtime piano - or the front page of a newspaper. I find it shallow and annoying.

I like the smaller watercolor, however. I can’t interpret any details, but overall, it does feel like it could be Saturday night at a Harlem dance club.

Illustration from "Thought Forms" by Besant and Leadbetter

(My pick)

The Intention to Know.—Fig. 19 is of interest as showing us something of the growth of a thought-form. The earlier stage, which is indicated by the upper form, is not uncommon, and indicates the determination to solve some problem—the intention to know and to understand. Sometimes a theosophical lecturer sees many of these yellow serpentine forms projecting towards him from his audience, and welcomes them as a token that his hearers are following his arguments intelligently, and have an earnest desire to understand and to know more. A form of this kind frequently accompanies a question, and if, as is sometimes unfortunately the case, the question is put less with the genuine desire for knowledge than for the purpose of exhibiting the acumen of the questioner, the form is strongly tinged with the deep orange that indicates conceit. It was at a theosophical meeting that this special shape was encountered, and it accompanied a question which showed considerable thought and penetration. The answer at first given was not thoroughly satisfactory to the inquirer, who seems to have received the impression that his problem was being evaded by the lecturer. His resolution to obtain a full and thorough answer to his inquiry became more determined than ever, and his thought-form deepened in colour and changed into the second of the two shapes, resembling a cork-screw even more closely than before. Forms similar to these are constantly created by ordinary idle and frivolous curiosity, but as there is no intellect involved in that case the colour is no longer yellow, but usually closely resembles that of decaying meat, somewhat like that shown in Fig. 29 as expressing a drunken man's craving for alcohol ---- text from "Thought Forms" (Project Gutenburg)

Tuchman points to Sixten Ringbom’s 1970 study of the beginnings of abstract painting to establish Kandinsky’s close ties to Theosophy - and his paintings do seem to echo the illustrations in "Thought Forms’’

Kandinsky, Study for a painting with a a White Form, 1913, 39 x 34

(Selected.by Tuchman)

In the “Thought Forms” lexicon, white is the highest intellect, yellow is strong intellect, blue is religious feeling. Surging against them is black (malice). Kandinsky has painted a cosmic drama.

Mikhail Matyushin (my pick)

A similar drama occurs here.

Evidently this avant-garde colleague of Kandinsky was reading the book at that time.

These early non-objective painters aimed so much higher than American abstract expressionists did fifty years later. They were seeking the mysteries of the universe - not just expressing their anxiety about living in it.

Between 1907 and 1915 painters in Europe and the United States began to create completely abstract works of art. It is neither our intention nor our interest here to resolve the issue of who was the first abstract painter or what was the first abstract painting. Instead we are more concerned with how this abstraction evolved and, in particular, how four leading abstract pioneers - Wassily Kandinsky, Frantisek Kupka, Piet Mondrian, and Kazimir Malevich - moved toward abstraction through their involvement with spiritual issues and beliefs. An examination of their development, and that of the generation following them, reveals how spiritual ideas permeated the environment around abstract artists in the early twentieth century.

In 1912 Kandinsky assessed the work of Matisse, pointing to his search for the "divine" but criticizing his "particularly French" exaggeration of color, and the work of Picasso, which "arrives at the destruction of the material object by a logical path, not by dissolving it, but by breaking it up into its individual parts and scattering these parts in a construc tive fashion over the canvas. For Kandinsky these approaches represented two dangers in contemporary art: "On the right lies the completely abstract, wholly emancipated use of color in 'geometrical form (ornament); On the left, the more realistic use of color in 'corporeal' form (fantasy). "Kandinsky advocated a different role for the artist:

The artist must have something to say, for his task is not the mastery of form, but the suitability of that form to its content. . .. From which it is self-evident that the artist, as opposed to the nonartist, has a threefold responsibility: (1) he must render up again that talent which has been bestowed upon him; (2) his actions and thoughts and feelings, like those of every human being, constitute the spiritual atmosphere, in such a way that they purify or infect the spiritual air; and (3) these actions and thoughts and feelings are the material for his creations, which likewise play a part in constituting the spiritual atmosphere.

Kandinsky, Last Judgment, 1912. (My pick)

And what a strange quote. First Kandinsky tells us that form is only there to serve content. But then when he enumerates the responsibilities of the artist, the only content mentioned are the "actions, thoughts, and feelings" of the artist as they engender a "spiritual atmosphere" - which sounds a lot like the indeterminable (meaningless ?) content of most abstract expression.

. . In Theosophy, vibration is the formative agent behind all material shapes, which are but the manifestation of life concealed by matter." As

Ringbom summarized, Kandinsky's expressed purpose was "to produce vibrations in the beholder, and the work of art is the vehicle through which this purpose is served.

If "vibration is the formative agent behind all material shapes" - then they are behind every shape ever made by artist and non-artist alike. If Kandinsky wanted to produce the specific vibrations that spiritually elevated the viewer - wouldn’t he have said so in a book called "The Spiritual in Art" ?

Kupka's involvement with the mystical and the occult dated from his early childhood in Bohemia. He was apprenticed as a youth to a saddler, a spiritualist who led a secret society. Kupka's visionary experiences were translated into visual form in his painting as a transperceptual realm in which color is imaginary, space is infinite, and everything appears to be in a constant state of flux. From his training at the Prague Academy with Nazarene artists, who stressed geometry rather than life drawing, Kupka came to master golden section theory and practice and perhaps to pass it on later to his neighbors in Puteaux, the Duchamp-Villon family. Frantisek Kupka, The Dream, 12 x 12", 1906-9

(Tuchman’s selection)

Kupka, First Step, 33 x 51, 1910-13 (Tuchman)

Kupka, Discs of Newton, 1912, 39 x 29

(My selection)

Kupka, Etude sur fond Rouge, 27 x 27, 1919

(My selection)

If this could be identified as a sacred narrative,

it would certainly be a compelling one.

Kupka, The Colored One, 25 x 21, 1919-20

(My selection)

Karl Diefenbach, Ad Astra per Aspera, c. 1900

(My pick)

In Vienna Kupka met Austrian and German Theosophists and found corroboration of his theory of reincarnation; in association with the painter Karl Diefenbach he further developed ideas about the reciprocal relationship of music and painting, and he became a sun worshiper, alert "to hues flowing from the titanic keyboard of color. " He credited Nazarenism with a desire to "penetrate the substance with a super-sensitive insight into the unknown as it is manifested in poetry or religious art. "

For Kupka, as for the Theosophists, the essence of nature was manifested as a rhythmic geometric force. Consciousness of this force was made possible by disciplined effort as a medium; Kupka was a spiritualist throughout his life. He announced in 1910 that he was preparing to state publicly his beliefs in theosophical principles and spiritual-ism; his 1910-11 letters to the Czech poet Svatopluk Machar note his fascination with the supernatural world, spiritualism, and telepathy and his need to express abstract ideas abstractly. The First Step, 1909-13 is a painting whose imagery is rooted in astrology and pure abstraction. The painting may be interpreted as a diagram of the heavens and as a nonrepresentational, antidirectional image referring to infinity and evoking the belief that one's inner world is truly linked to the cosmos. Years earlier Kupka had written of a mystical experience in which "it seemed I was observing the earth from outside. I was in great empty space and saw the planets rolling quietly.

Some rather intense paintings - but what happened to Kupka after 1923,? All I can find are representations of what appear to be machines. Did he abandon spirituality? Was "spirituality" just a passing enthusiasm of his or his collectors?

Piet Mondrian, Composition in Black and White, 1917, 42 x 42

(Selected by Tuchman from the exhibition)

Mondrian joined Amsterdam's Theosophical Society in 1909, but there is evidence that his interest in spiritual ideas began around 1900.

In this volume Carel Blotkamp demonstrates that Mondrian exposed himself to a variety of theosophical ideas shortly after the turn of the century: he read texts, including Schuré's Les Grands Initiés, and associated with theosophical sympathizers, including critics, collectors, and painters; in addition, he met the painter . Jacoba van Heemskerck in 1908 at Domburg, while visiting the Symbolist Toorop. Unlike Kandinsky, Mondrian did not borrow visual imagery, such as aural projections, from theosophical texts but rather invented an abstract visual language to represent these concepts . His devotion to Theosophy and related beliefs was quite strong.

If Mondrian had ever written something to that effect, I’m sure Tuchman would have quoted it here.

Also contributing to Mondrian's artistic outlook were his impressions of the paintings by the Symbolist generation preceding him, most notably those by Toorop and Thorn Prikker, and the traditions of precise geometry in Dutch art, which set the stage for his experience of Cubism, first encountered in 1910. Mondrian's theories and art were based upon a system of opposites such as male-female, light-dark, and mind-matter. These were represented by right-angled lines and shapes as well as by primary colors plus black and white. His abstract language employed an unusually direct system of equivalences to express fundamental ideas about the world, nature, and human life and to evoke the harmonious unity of opposites.

Tuchman offered no footnotes to document any Mondrian theory of opposites - while Wikipedia does offer the following quote from a letter written in 1914 - and the verbiage is aesthetic, not spiritual:

… and note that for Mondrian, the foundation of truth in his work is "external" — i.e. relating to what can be seen in the physical world. The hidden world remains hidden. We could call his work spiritual - but then all delightful graphic art would be so as well.

Kazimir Malevich, TheWoodcutter, 1912, 37 x 28

(Selected by Tuchman from the exhibition)

Makevitch, Suprematist painting, 1917-8, oil on canvas, 38 x 27

(Tuchman)

Malevich fused his interest in the fourth dimension with occult, numerological notions shared with him by his close friend the poet Velimir Khlebnikov.

Malevich's art moved from the Alogical representation of space to its final, totally abstract form: Suprematism. Suprematist works (Suprematist painting 1917) were intended to represent the concept of a body passing from ordinary three-dimensional space into the fourth dimension.

Malevich's knowledge of Cubism (Woodcutter) helped him move in this direction, although he stated that his inclination toward abstraction predated this influence.

"Suprematist Painting 1917" may indeed represent a body passing into the fourth dimension. —- but it seems like more of a gimmick than a painting. I’d say the same about Woodcutter as well.

Kazimir Malevitch, Suprematist Composition, 1916

(My pick)

El Lissitzky, untitled, 1919-20

(My pick)

Further down in the text, Tuchman identifies Lissitsky as one of those few early abstractionists whose work was not spiritual at all. Presumably he was referring to Lissitsky’s career in graphic propaganda for the Soviet state. But how was his art different from Malevich back in 1920?

Picasso, Evocation (burial of Casagemas), 1901

Tuchman then briefly enumerates some other examples of spirituality in Modern painting. I can’t think of a painter more worldly than Picasso - but when he was 21 and his good friend shot himself, Picasso did make a painting that recalls El Greco, if not spiritually. (Lots of cute, nude babes in Picasso’s heavenly vision)

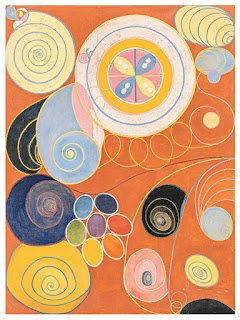

Hilma af Klimt, No. 1 , 1906, 14 x 19 "

(Tuchman)

More to the point of spirituality would be Tuchman’s introduction to Hilma af Klimt (1862-1944) - whose work had never appeared in an art museum until he chose it for this exhibition.

There is a happy wackiness in the above piece that I don’t find in her other pieces.

Giacomo Balla, Irredescent Interpenetration, 1914

(Tuchman)

Boccioni, Dynamism of the Cyclist, 1913, 28 x 37

(Tuchman)

Boccioni's description of his goal for painting to take on "spiritualization" certainly reflects his interest in the fourth dimension "Theoretically, " Boccioni wrote in 1908, "I'm for everything that is grandiose, symphonic, synthetic, abstract." He spoke of his search for a "new, definitive sublime in art," an art of "exaltation and self-oblivion" and cited photographic proof by the medium Eusapia Paladino of the existence of "luminous emanations of our body. "

That hardly makes Boccioni, or his art, especially spiritual -

though his paintings do have a strong, vibrant, radiating spirit.

Detail of above

(But could also stand on its own. Quite thrilling)

Georgia O’Keefe, Series 1, Number 1, 1918

(Tuchman)

Between Emerson and the pioneering painters of the 1910s only Ryder intervenes as a spiritual painter of strength who possessed a resonant vision that was neither illustrative nor facile. Emerson was correct when he predicted in 1845, "After this generation one would say mysticism should go out of fashion for a long time. "

As noted earlier, mysticism in American art at the turn of the century was nature oriented and nonsacred in its associations. Painters of appropriate disposition generally began with landscape imagery, and their work gradually became abstract. Dove's paintings before 1920 coincide with his interest in vitalism; works after 1920 were directly inspired by Theosophy and reflect his interest in astrology, occult numerology, and the cabala. Hartley's early involvement with the occult is evident in works inspired by Native American art, such as Painting No. 48, Berlin, 1913 . Certain of Hartley's Berlin abstractions made around 1914 refer to Paracelsus and to the English mystic Richard Rolle.

O'Keeffe was influenced by texts in Alfred Stieglitz's Camera Work, particularly by Max Weber's 1910 essay on the fourth dimension. She conceived of making abstract paintings in a serial manner as early as 1918 (her watercolors date from1916). Blue Line 1, 1918, and Series 1 No. 1 and Series 1 No. 8, both of 1919 , were identified by the artist as part of a group of works titled with numbers rather than landscape evocations.

O’Keefe’s connection to spirituality is rather thin - other than for the evident spirit in her paintings.

And we might also note how the moral spirituality of Emerson differed from the more personal mysticism of Madame Blavatsky.

Arthur Dove, That Red One, 1944, 27 x 36

I wonder why Dove’s paintings do not accompany the text here..

Perhaps his mysticism, if any, was still "nature oriented",

and his pieces, like the above , were based on landscapes.

Above, it appears that he painted the sun as a black disc.

At a time when abstraction was unpopular in the United States, especially outside New York, a remarkable fusion of the spiritual and the abstract occurred in Taos, New Mexico, when Raymond Jonson and Emil Bisttram founded the Transcendental Painting Group in 1938. Chaired by Jonson, the group included Agnes Pelton, the Canadian artist Lawren Harris, and others who were involved with Theosophy. Kandinsky certainly influenced all these artists; On the Spiritual in Art no doubt was known to, if not read by, all members of the group. Jonson had read Kandinsky as early as 1921. Later he was to recall that he experienced mystical sensations in 1929 and began a period of "really abstract" painting. He cited several key ways that the spiritual is expressed in art, particularly the use of occult symbols, as in Bisttram's work

Raymond Jonson, Composition 4, Melancholia, 1925, 46 x 38

(Tuchman)

Of the science series, Jonson wrote in his Technical Notes, “These studies represent my concept of the spiritual side of modern youth, with the idea that contemporary knowledge offers an emotional and spiritual approach. When the panes are finished I hope to have created not only an ideal wall decoration but works possessing a spiritual quality. I think of them as symphonic compositions consistent with my medium and honest to the highest ideal I stand for”

Emil Bisstram, Pulsation, 1938, 60 x 45

(Tuchman)

Lawren Harris, Abstract painting #95, 56 x 46, 1939

(Tuchman)

Lauren Harris, Ice House, Coldwell, Lake Superior, 37 x 44, 1923

I prefer his eerie, spiritualized northern landscapes, like this one.

(My pick)

Agnes Pelton, The Ray Serene, 1925, oil on canvas

(My pick)

Pelton is my favorite transcendentalist.

Agnes Pelton, White Fire, 1930

(Tuchman)

Agnes Pelton, Idyll, 20 x ?, 1952

(My pick)

She possibly did see something like this one day.

Jean Arp, Flower Veil (aka Hammer Flower), 1916, 24 x 19 x 3

(Tuchman)

Artists of a later generation, such as Jean (Hans) Arp, accepted that abstract art was meaningful and indeed spoke to deep philosophical issues. He wrote, "The starting-point for my work is from the inexplicable, from the divine. A single, quivering, in-exact shape recurs in Arp's work: the Ur-form, the double-ellipse, "that archetypal figure, a designation of certain closed curves that resemble the figure 8, described by Goethe in his poem 'Epirrhema': Nothing's inside, nothing's outside, / For what's inside's also outside. / So, do grasp without delay / Holy open mystery. " Arp's interest in mystical and occult sources has parallels in the work of other artists who explored the possibility of a basic form underlying all life and the meaning of dualities in the cosmos.

This connection to spirituality appears tethered to only a quote or two.

Karl Schwitters, Abstract Composition, 1923-5, 30 x 20

(Tuchman)

Aside from Arp, the most notable exception to this, however briefly he may have been interested in mystical concepts, is Kurt Schwitters. John Elderfield recently assessed the spiritual influences upon Schwitters: a belief in animism and hylozoism and Kandinsky's ideas of the inner sound. Schwitters was delighted by Herbert Read's citation of "the mystic" in his work." In 1924, when Schwitters called Dada "the spirit of Christianity in the realm of art,he was working on two canvases of an unusually geometric cast, relating to the golden section, paintings that play on proportions and measurement in a distinctive manner.

Couldn’t we say that every good painting exemplifies hylozoism ?

Every mark within is alive and intelligent.

And Schwitters was a wonderful painter and graphic designer.

Suzanne Duchamps, Broken and Restored, 1918

(Tuchman)

Jean Crotti, Chainless Mystery, 1921

(Tuchman)

Jean Crotti, in Space, 24 x 18, oil on canvas

(My pick)

Jean Crotti, Circles, 36 x 14, oil on canvas, 1922

(Tuchman)

I wish more had been said about Marcel Duchamps' brother-in-law, Jean Crotti.

I’m charmed by his designs.

Lee Mullican

(My pick)

Lee Mullican, the Ninnekah, 55 x 30, 1951

(Tuchman)

Mullican, Wolfgang Paalen, and Gordon Onslow Ford arrived in the city at roughly the same time in the late 1940s. Their shared interests culminated in the seminal Dynaton exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Art in 1951, which included their work alongside objects from their collections of pre-Columbian and Native American artifacts. Out of the Dynaton came the idea that the practice of making art was an exploration of deep levels of being that could open up higher levels of consciousness for all humankind.

The Ninnekah is named for a wild area of Oklahoma, inhabited by the Choctaw people, where Mullican was born and raised. He applied paint to the canvas with the edge of a printer’s knife, building up the surface with thin striations of yellow, orange, and pink that radiate out from a prominently placed sunlike orb. Below lies a quieter orb within a pale teal triangle, perhaps denoting an earthbound locus of cosmic energy.

Ninnekah resembles the tie-dyed fabric aesthetic of the 1960’s.

Could Tuchman have called that "spiritual art" as well ?

Probably not - but only because it was not marketed as such.

Barnett Newman, The Voice, 8’ x 8’91", 1950

(Tuchman)

To this approach Newman opposed his own intentions and those of Gottlieb, Rothko, Pollock, and others of the emerging New York School:

The present painter is concerned not with his own feelings or with the mystery of his own personality but with the penetration into the world mystery.

His imagination is therefore attempting to dig into metaphysical secrets. To that extent his art is concerned with the sublime. It is a religious art which through symbols will catch the basic truth of life.

.. The artist tries to wrest truth from the void,

Newman spoke on behalf of the Abstract Expressionists when he declared that the

"new painter feels that abstract art is not something to love for itself, but is a language to be used to project important visual ideas. ". When he expressed his desire "that the shapes and colors act as symbols" that will elicit "sympathetic participation with the artist's thought, " one is struck by the echo of Baudelaire's yearning "to illuminate things with my mind and to project their reflection upon other minds.

Just wondering what metaphysical secret ever required a Barnett Newman painting to be revealed.

Also wondering which abstract paintings Newman dismissed as "decorative" during his career as an art critic.

As Newman introduces the word "slogan" into his discussion of contemporary art, we might then query whether or not it applies to his ideas as well. Is he really pursuing a higher level of spirituality - or is he just using that highfalutin language to promote himself and others like him?

No one person should be blamed (or credited) for the triumph of concept over visuality in the 20th century artworld. It’s been so useful for marketing and institutionalizing contemporary art. But Newman certainly encouraged it.

Ad Reinhart, untitled, 1964

(My pick)

The interest in myth and the unconscious, coupled with an interest in Native American sources, encouraged American artists' receptivity to other non- Western ideas, including Lao-tzu, Zen, and the I Ching. The Singyo, or Heart Sutra, sums up the central meaning of Zen thought, according to Alan Watts: "What is form that is emptiness, what is emptiness that is form. " To study a black painting by Ad Reinhardt involves a process similar to Zen meditation - a deceptively simple affair that "consists only in watching everything that is happening, including your own thoughts and your breathing. Granting one's vision sufficient time to perceive the resonant hues and shapes in a painting by Reinhardt is equivalent to the assumption of meditative position. Then the painting seems to yield its essence all at once, recalling the comment of an Indian musician: "All music is in the understanding of one note.

Why would such a study be any less rewarding if the object of contemplation was any other black or mostly black square?

Richard Diebenkorn, Ocean Park I, 80 x 62, 1967

(Tuchman)

"I have one reservation - otherwise for me it will be a grand show and book. I'm writing this down so that it will come out as I mean it which is usually not the case when i try to put something conversationally.

"You do refer to the formal

experiments of Cézanne, Impressionists, and the Cubists as culminating in abstraction and you called it the 'traditional

viewpoint

"But the over-all impression I get from your alternative interpretation is that you give it all to the mystics and the spiritualists in regard to the genesis and development of abstract and non-objective painting. For me, in large part, the prospectus shapes up as a kind of refutation of the traditional viewpoint rather than a much needed illumination of the total picture.

My exception is based on the fact that abstract painting was a formal invention. Also, that major turns or changes in art historical stvle are not come by easily, overnight, or by individual artists (another

traditional view point tells us that Kandinsky invented non-objective painting). What seems to get lost in your prospectus is that the formalist line from Cézanne through Cubism arrived at a point on the threshold of total abstraction wherein it was implicit, and for the most astute artists a clear option. That both Picasso and Matisse at different points in their careers rejected the crucial step is irrelevant. They had come the distance in a difficult and prolonged process of abstracting and simplifying, as did several of their

'formalist' peers.

I appreciate Tuchman for sharing this dissenting letter - though I do disagree with its argument.

As Diebenkorn points outs- the historical path to non-objective art was paved by non-spiritual artists like Cezanne, Matisse, and Picasso. But the final step was the most important step: turning away from recognizable subject matter - and it was taken by artists who had spiritual intentions.

At least - that’s how Tuchman is presenting them, - even if I think they took painting far more seriously than spirituality. Mostly they seem like dabblers in the occult.

Mark Rothko, Vessels of Magic , 1946, 38 x 26

Mark Tobey, World Egg, 1944, 24 x 19

Mark Tobey, Space Rose, 1959, tempera on paper, 16 x 12

Morris Graves, Rising Moon, 1941

Tuchman provides spiritual associations for the above three artists - but they’re no more substantial than reading a chapter of "Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintainance"

Frank Stella, Getty’s Tomb, 1959, 84 x 96

In Frank Stella's view, sufficient sufficuent abstract art was created between 1920 and mid-19sos for him to use as raw source mate. rial. Although Stella has maintained a professional position to the contrary, the fact that his black paintings suggest mandalas as well as tantric diagrams may have been the result of his interest in non- Western ideas. His interest in Celtic illumination, for example, is documented by his studies on the subject at Princeton as an undergraduate. By 1964, however, Stella was adamant that in his art what you see is what you see. " Nevertheless, his black paintings, such as Getty Tomb, 1959 were generally regarded as mandalalike when they were created.

Thankfully, Tuchman has mostly avoided the passive tense so far in this essay - until now.

Morris Graves, Black Buddha Mandala, 1944, 26 x 26

At a time when Graves was deep into the study of Hindu philosophy, the Black Buddha Mandala appeared to him in a dream. He recorded that he saw two concentric circles of light against a sepia-dappled, slate-like ground. Within this luminous mandala appeared four smaller circles, one after another, which contained different stages of a plant bud as it progressed toward flowering. Finally a voice addressed itself to Graves with the words, “You see the eternal laws are working.” Then another mandala appeared at the center, and it contained the image of a seated black Buddha.

Graves recorded the vision in his painting, but afterward considered the image of the Buddha too personal to display, so he covered it with a circle of rice paper.

And when we actually do have documentation of a spiritual connection to a piece, it’s visuality is boring.

Clyfford Still made abstract paintings of great importance, and his absence from the exhibition The Spiritual in Art is due only to a lack of understanding about his specific sources as an artist: only cryptic references in his teaching allude to his involvement with mystic belief systems.

From yet another vantage the search for abstraction, the means to communicate that which is otherwise impossible to project, has come full circle: the inchoate abstraction of the Symbolist generation now reappears in the paintings of contemporary artists, who have so thoroughly absorbed lessons drawn from the history of nonrepresentation as to make the issue of abstraction less poignant. For example, a comparison of Hodler's The Dream, 1897 , with Bruno Ceccobelli Etrusco Ludens, 1983 shows that the image conjured in the earlier work is assimilated pictorially and imaginatively in the recent painting. Indeed, this complete absorption of the unknown into the frankly expressed could not have occurred without the invention, development, and continual reinvention of abstract painting between the 1890s and the current period.

I’m surprised that any notable abstract painter had reason to be excluded from this catalog - unless, like Diebenkorn and Stella, they vehemently denied any connection to the spiritual.

Bruno Ceccobelli, Etrusco Ludens, 1983, 78x93

Ferdinand Hodler, The Dream, 1897, 37 x 25

Both paintings do feature a triangle atop a rectangle — but how do we know that Ceccobelli got that arrangement from Hodler? Without evidence, it’s far fetched. If that was the most obvious example that came to his mind - the premise is highly unlikely.

Anselm Kiefer, Piet Mondrian and the Battle of Arminius, 1975, 8’ x 3’9"

Another image may be taken as a veritable icon of this utter assimilation of abstraction in contemporary art. Anselm Kiefer, who is not interested in abstraction per se, created in 1976 an immense canvas entitled Piet Mondrian: Arminius' Battle .The painting depicts the growth of a tree from the vertical-horizontal abstraction of Mondrian. Just as Mondrian transformed the tree image, moving from representation to abstraction, with a mediating infusion of mystical ideas, so Kiefer now reverses the creative process by creating an image that commences from antimateriality and then evokes the meaning of a tree in winter. Arminius's victory over the Roman invaders several years after the death of Christ was a triumph secured by the secret gathering of a great force of allies, and in a sense so, too, was the victory of Mondrian and his colleagues in the formulation of abstraction in the 1910s. Kiefer's transcendence of the abstract-representational polarity is a brilliant icon, a statement that true spiritual abstraction need no longer be doctrinaire in its exclusiveness.

This does seem to be a compelling painting - contrasting the orthogonal order of civilization (Mondrian) as it rises up from the angular chaos of barbarity (the treacherous German tribes). It suggests that order and chaos need each other - which is not especially a forward and upward kind of spirituality.

The Kroller-Muller museum , current owner of the piece, presents it as a reflection on "change and renewal"

BTW - the Battle of Teutoburg Forest occurred in 9 A.D.. The pre-teen Christ was still quite alive and presumably hanging out in his father’s wood shop.

If "occult" refers to hidden meanings, I would like to know what meaning was hidden within the above painting.

And if there is no consensus of experts - may we suggest that it’s spirituality was a marketing tool rather than a path to enlightenment?

*****************************+

Overall — if we may assume that Tuchman has shared every connection to mystic belief systems that could be found - this essay has proven the reverse of its premise. Nameable spiritualities may have interested many of these artists at some point in their careers - but judging by what they left behind, it was the spirit in their paintings that interested them much more. And a word that denotes spirit infused shape(s) is "form".

Why can't we accept this kind of non-doctrinaire formalism as a spiritual practice all by itself - regardless of associated belief systems. It can be recognized in every culture and period - even if it’s sometimes quite rare.

We also might note that not one "hidden meaning" has been revealed in this essay - despite the promise implied by its title.

So had I been curator, I would have titled the show

"The Religion of Form and the Rise of Secular Spirituality"

… and included pieces by Diebenkorn, Stella, and Lissitsky

…while excluding Johns, Newman, and Marden.

And my exhibition catalog would only have consisted of reproductions

(with plenty of gorgeous details)

and laudatory poems instead of scholarly essays,

similar to the colophons appended to the scrolls of Chinese brush paintings.

No comments:

Post a Comment