The Generation Gap

This is the third essay in the catalog for "The Rise of Landscape Painting in France, Corot to Monet", a 1991 exhibition at the Currier Gallery of Art

Note: Quoted text appears in orange. Some of it comes from this essay by Fronia Wissman. Other quotes come from the uncredited catalog text that accompanies the reproductions.

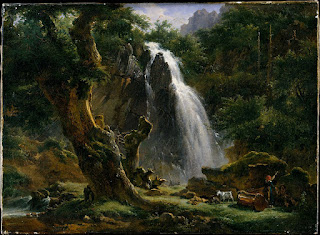

Narcisse Diaz Virgile de la Pena, Early Autumn Fontainbleu, 1870

Wissman addresses the great question posed by this exhibition: How did French plein-air painting get from the painters of 1830 (Rousseau, Corot, De la Pena) to the painters of 1860 (Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley) ?

(Since this is the first time De la Pena has been mentioned in this book, I have shown him above. It's at Cincinnati's Taft Museum though I can't remember seeing it. Other paintings - perhaps by Constable - must have sucked up all the energy in the room )

Wissman proposes that this "generation gap" is "not only the natural succession of youth following old age, but also the shift from a state sponsored art world to a private market in Paris".

I would dispute this theory because the 1830 landscapes were also sold mostly on the private market, not to institutions of the state or church. Wissman shares this quote from that great rebel, Courbet: "To become known you have to exhibit, and unfortunately there's only this one exhibition". But that did not stop him from continuing to make his unconventional paintings. And if we look back earlier into the history of the French Academy, we would find that Watteau was invited to join despite his unconventionality, and Chardin who was asked to hang the annual Salon despite practicing the minor genre of still life.

Jean-Achille Benouville, Roman Countryside, 1843

View in the Roman Campagna acknowledges the still well-rooted French admiration for the clear skies and timeless subject matter offered by the hill towns surrounding Rome, an affection that had dominated French landscape painting for two centuries. But in emphasizing the arching tree that shadows a band of resting fieldworkers as well as much of the foreground, rather than a prominent monument or an identifiable city profile, Benouville wrested a margin of freedom from the conventions that made so much Italianate landscape painting static and studio-bound. The irregular alternation of light and shadow that organizes the space and offsets carefully studied details and textures is inherited from the English landscape tradition so much admired by Dupre and Troyon, while Benouville's grand tree echoes Rousseau's work of the 183os. The cow herd and resting harvesters take their roles from the terrain they inhabit. The landscape does not rely upon the figures for its own significance.

Throughout the 185os and 186os, Benouville brought an earthy naturalism to the content of his Italian landscapes, but unlike his colleagues working in French forests and pastures, he remained simultaneously committed to a degree of precision and detailed craftsmanship that they chose to forego in favor of greater immediacy. (Uncredited catalog text)

Regretfully, we are given no examples of those Italianate paintings which feel static and studio bound. Though actually, that's how this piece feels to me -- but not in a bad way.

The restful trees, cavorting country folk in the shadows, and distant classical arcade makes me think of Corot who also happens to have once shared a studio in Rome with this artist. Corot, however, preferred the silver light of dusk.

Contrary to the opinion quoted above, this landscape does seem to rely on figures for its significance. The figures draw our attention and draw us into this lively yet peaceful vision. It feels like a stage setting for a masque similar to "As You Like It"

Jean-Achille Benouville, Colosseum Viewed from the Palatine, 1844

This appears to be a painting I could really love. The air is alive with possibilities. The Colosseum was built as a theater for blood sport - but here it has become a place for fruitful contemplation in harmony with the natural world.

It's a shame that the Dahesh is the only museum in America that puts his work on public display ( if or when it eventually re-opens)

Achille-Etna Michalon, Waterfall at Mont Dore, 1818

Birch Trees, 1821-22

The Tree (??? ), undated

Michelon (1796-1822) enters this discussion as the first teacher of Corot. As the winner of the very first Prix de Rome for historical landscape, his tutelage qualified Corot to exhibit in the Salon.

One might note, however, that this short-lived artist painted in a variety of styles that were not especially academic. A close-up detail of his Waterfall at Mont Dore seems quite close to what Courbet would later do -- while his emphasis on stark, bold pictorial space in "Birch Trees" might be mistaken for post Impressionism.

Jean-Victor Bertin, 1804

Corot ( as well as Michalon) also studied with Bertin. There certainly is a resemblance to many paintings by Corot - though it's saccharine enough to be printed on a collectors plate. I can see why Corot's atmospheric evening views are much better known.

Bertin, 1810-13

Bertin, 1808

These angular cityscapes, however, are much more pleasing.

Jean Charles Joseph Remond, (1795-1875)

Mountain View with Road to Naples, 1821-5

Remond, Naples Riviera di Chiaja at night, 1830

Remond, , View of the Basilica of Constantine from the Palatine, Rome, 1822-25

Remond, Grotto of Posilipo, 1822-4

Remond, Eruption of Stromboli, 1842

Remond enters the discussion as the first teacher of Rousseau. Obviously, the pupil went in a much different direction. But Remond went in several directions himself. Many are like picture postcards for tourists. The volcanic eruption is quite Romantic, however, while his oil-on-paper sketch of the Basilica of Constantine is as lively as the Fauves.

The other pedagogues mentioned were figure painters, not landscapists, so I'm omitting them.

Above is Millet's entry to the 1847 Salon. He's turned the first part of the Oedipus myth into the drama of a young woman dramatically saving a child. I'm glad he turned to painting peasants.

Troyon, The Game Warden, 1854

There is almost an equal latitude in Troyon's technique. It varies from being neoclassically crisp in drawing and accent to being exeptionally loose and paintererly. In the same picture, The Game Warden of 1854 from the present exhibition, one can, for example, experience an almost inconceivable combination of seemingly incompatible imaging practices derived in equal measure from Millet, Corot, and Courbet.

If only Wissman had elaborated on these "imaging practices" The inward pulling triangles and rectangles make this piece so static, heavy, and quiet. Perhaps Wissman felt that the dog came from Courbet, the warden came from Millet, and the trees from Corot. Who knows?

If the generation of 1830 had one composite painter, it was Troyon. But to say this is not to deny Troyon an artistic personality of his own. Rather it is to say that his personality was by nature happily eclectic and genuine in its enthusiasm for many things. While never as committed to the painting of a particular species of animal as Jacque was to sheep, Troyan made something of a specialty of animals, particularly after 1850. Here, as in his work generally, references abound. This exhibition's Pasture in the Touraine of 1853 invokes Albert Cuyp's and Paulus Potter's famous cattle pictures from the 1650s. Troyon even manages to approximate a seventeenth-century Dutch edginess in his treatment of light. (Uncredited catalog text)

Albert Cuyp, 1650

Troyon is so much more about gravity and earthiness than either Cuyp or Potter.

Potter is more like a cartoonist - but Cuyp's cow pasture is luminous and uplifting. Possibly he was Hindu in an earlier life.

Troyon, Descent from Montmartre, 1850

Descent from Montmartre reflects Delacroix and Jacque, depending on what aspect of the picture one examines.

Delacroix for human figures, Charles Emile Jacque for sheep ? Regardless-- it feels tired, broken, confused, and boring to me.

Perhaps the most distinctive Troyon in the present exhibition is the earliest one, the View of Saint-Cloud of 1831. Besides being highly informative topographically in terms of landscape and architectural elements, the painting manages to join this informativeness to a broadly dispersed group of variously costumed figures in the foreground in such a way as to evoke a distinctly eighteenth-century jete galante ambience. Information is combined with loose, poetic feeling easily, even brilliantly, as Troyon unifies the image with a consistent treatment of rather bright natural light and a comparatively uniform scale of brushmarkings. The latter are sufficiently small and delicate to accept clearly drawn edges when such are necessary, and the painting as a whole shows, as clearly as any Troyon ever will, what broadly informed taste and technique alone make expressively possible. (Uncredited catalog text)

It is a bit ironic that the most distinctive Troyon in this exhibit is the one least identifiable as his work.

Wissman goes on to tell us how the painters of 1830 built their reputations by studying with Academy artists or following established models or appealing to specific tastes. Corot succeeded in getting the above government commission for a chapel. It certainly is a tribute to the Italian Renaissance - though it feels less like sacred painting and more like a collection of model studies. The pictorial space feels a bit broken.

Daubigny received a government commission to make etchings of paintings (of his selection) in the Louvre. It was a way to disseminate culture to museums in the provinces. Not a bad idea! And his monochrome interpretation stands up to the original pretty well - at least in these reproductions.

This piece was too sedate for me back when I was a teenager wandering through the Cincinnati Art Museum. But it is so damp and luscious. As Wiss tells it, it made his career, winning an award at the Salon and acquired by the Emperor. He specialized in water scenes ever after, buying a barge so he could paint them as he floated downstream.

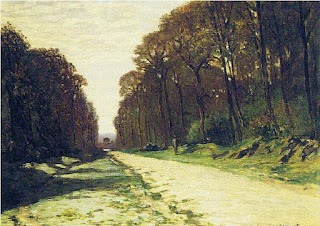

Theodore Rousseau, Forest of Compiegne, 1833

"Rousseau's "Effet de Givre" exemplifies the freer manner that was popular with people whose taste was more liberal than that of the Salon jury members who were concerned with issues of academic technique"

More importantly, it exemplifies a cold, dark, ominous vision of the natural world. Could we call Rousseau the first Expressionist ?

Wissman has demonstrated that Rousseau, Corot, Daubigny, and Troyon did things to further their careers and finances- but that does not account for why we care about such biographical details in the first place. He then notes that in the 1860's, aspiring artists, like Claude Monet, were still interested in what was happening in the Salon:

After working with Eugene Boudin in Le Havre, Monet went to Paris in the spring of 1859 to see the contributions of the major landscapists at the Salon. He reported to Boudin after his first visit:

"In quality the Troyons are superb, the Daubignys are for me something truly beautiful. In particular, there is one of Honfleur that is sublime. There are some nice Corots, some nasty Diaz, for example. " After his second visit two weeks later, Monet wrote again: As for the Troyons - there are one or two enormous ones -the Return to the Farm is marvelous, with a magnificent sky, a stormy sky. There is much movement in it, there is wind in the clouds; the cows, the dogs are completely beautiful. There is also the Departure for the Market; it is a mist effect at dawn. It is superb and particularly luminous. A View Taken at Suresnes is of an astonishing scope. You would think you were out in the country; there are animals in a body; the cows in all sorts of positions; but it has movement and disorder .. . . Theodore Rousseau made some very beautiful landscapes .... Daubigny, now there is a fellow who does well, who understands nature! ...The Corots are unadorned marvels.

At the beginning of his career, Monet, age 19, as he reported to Eugene Boudin, age 35, was much more interested in capturing the shapes and effects of nature than in whatever might be imagined.

The works by Troyon and Corot are not those we would expect Monet to find "superb" and "unadorned marvels." Troyon's works were variants on his enormously successful animal pictures. The lofty, cloud-filled skies are not the subject of the paintings; rather, they are the background to the herds of cows and flocks of sheep dominating the foreground . Indeed, Troyon's animals became so popular that he could not meet the demand himself; he hired Boudin in 1861 to fill in the backgrounds of his pictures while he concentrated on the animals.

I'd like to see some of those Troyon-Boudin collaborations, but have been unable to find any online.

I admit to having had a strong aversion to paintings of herds of cattle or sheep. It was a favorite subject matter of the Barbizon school which is over-represented in the art museums of Cincinnati. My initial reaction on seeing one has always been "Oh God, not another one!" Perhaps this reflects my peasant ancestry. I'm more tolerant of them now, however.

Corot, The Moored Boatman, 1861

Corot's works in the Salon of 1859 (to which Monet referred above) were not pictures that we have come to identify with him, such as the Moored Boatman... rather they were enormous, dark, brooding pictures with subjects taken from Dante or Shakespeare. For Monet these paintings represented the pinnacle of contemporary landscape painting...... he discovered the strength of Corot's compositions, his method of picture making, apart from the story being told

I find this surprising as well - though the young Monet's admiration for these dark, brooding pieces does not mean that he would have admired Corot's more scenic landscapes any less.

And he may have changed his mind as he matured. For me, these conflations are no more than curiosities that serve neither the literary material nor Corot's kind of landscape.

Though Charles Baudelaire would beg to differ:

He (Corot) is one of the rare ones, the only one left, perhaps, who has retained a deep feeling for construction, who observes the proportional value of each detail within the whole, and '(if I may be allowed to compare the composition of a landscape to that of the human frame) the only one who always knows where to place the bones and what dimensions to give them.

We're told that this 34 year old artist was following academic convention when he made a smaller oil paint study for a larger finished piece. The study has the rougher feeling of a real place,. The finished piece is more like the dreamy fantasy of a Classical landscape. It's been manicured.

This piece is presented as the young Monet's attempt to please the Salon by including figures. Apparently, however, that ploy failed - the painting was rejected - possibly for other reasons.

This large piece came to Chicago about 15 years ago. It felt rather goofy - not worth looking at. But it does present a fearless ambition to experiment. So it could be called "modern".

Monet: Camille in a Green Dress, 1866

Here's another example of Monet painting the figure at that time.

Were it no attached to the name of Monet, it would probably not be now showing in an art museum.

Monet: Zaan at Zaandam, 1871

Here's a brief chronology of the Salon in those years:

1848 : artists began to the salon jury

1857: turning more conservative, only academy members were qualified to serve on the jury

1863 - Napoleon III establishes the salon Des refuses for the Impressionists and the academy is restructured.

In 1866 and 1868 Daubigny sat on the Jury and he supported the newer art. He purchased Monet's painting of the Zaan shown above.

Impressionist salons would follow in 1874, 1876, 1877, 1879, 1880, 1881, 1882 and 1886

Daubigny: Fields in the Month of June 1874

Above, it appears that Daubigny was also beginning to paint more like the Impressionists, though I would agree with Corot that "His field of poppies is blinding..there are too many"

Monet, 1881

Monet's version is so much more light, breezy, and delightful

Guillemet was a protege of Corot, as well as an acquaintance of Manet, Monet, Cezanne, Pissarro, and Courbet. (I see more Courbet than anyone else in the above earlier work)

Corot advised him to submit work to the Salon of 1874 instead of the independent exhibition that included many of the Impressionists. Upon gaining entry, Corot remarked "Well, this little Antonin saved at last! When he was with that dirty gang, I thought he was lost forever".

And so we have Monet firing back with:

The good Corot. I don't know about that, but what I do know is that he was very bad for us. The swine! He barred the door of the Salon to us. Oh, how he slashed at us, pursued us like criminals. And how all of us without exception admired him! I didn't know him. I knew none of the 1830 masters; they didn't want to know us ... . Only Diaz and Daubigny defended us, the latter energetically. He was on the jury, and he resigned [in 1870] because we were turned down.

Guillemet, Port de Barfleur (date unknown)

Concerning Millet, Corot wrote:

For me it is a new world; I no longer recognize myself there; I am too attached to the old ways. I see there a great knowledge of atmosphere, of depth; but it frightens me. Tam slow in getting used to this new art. It has been only recently, and after having been for a long time distanced from it, that I have finally understood Eugene Delacroix, whom I now regard as a great man.

And so we have the "Generation Gap"

Corot has modified Classicism with a plein aire sense of atmosphere and real foliage, but he still is seeking the timeless truths, not the thrill of the moment. I can see why Delacroix and Monet disturbed him - but I don't see how Guilllemet would have especially pleased him. Perhaps it was more of a political, strange-bedfellows kinds of thing.

Wissman concludes that : "The generation gap - best demonstrated by Corot's incomprehension of Monet's technique and subject matter and Monet's reluctance to submit himself to tradition - in the end rested not so much on matters artistic as economic. Changing institutional structures meant that the strategies of self promotion that had worked for the Men of 1830 were no longer available for the young Impressionists "

There's no way to prove or disprove such a statement. When painters seek fortune and fame they may well develop a heart felt positive feeling for whatever kind of painting got that for them. But this does seem to be a theory that precedes rather than follows what Wissman has written in this chapter. Exhibition history cannot account for exhibition success - either then or now. Nor can it account for the difference between the two competing salons.

No comments:

Post a Comment