Kermit Champa : The Rise of Landscape Painting in France - Corot to Monet

*******************************************************************

INTRODUCTION BY RICHARD BRETTELL

********************************************************************

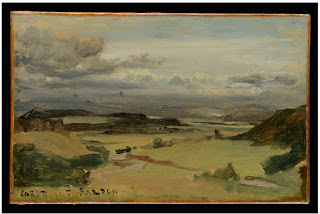

Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes,

Study of Clouds over Campagna, 1782-85

This exhibition catalog had me puzzled until I read Champa’s “Methedological Notes”. The project was organized to mark the inauguration of a new director of the Currier Gallery. She got Champa, her former advisor at Brown, to write the title essay and he got his students to write commentaries on each of the pieces shown. Giving him free reign to write whatever he wanted, she also commissioned two other essays to cover the subject in a more conventional way. The essay by Brettell is called the “Introduction”, one may conclude, only because it was placed in front of the other two.

Brettell kicks off his introduction with a tribute to Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes. He was good at the kind of historical landscapes preferred by the Academy - but he was outstanding at plein aire studies - which, unfortunately - I have never seen. The Met owns a few and currently has only one on display.

And then there’s his book about landscape painting. Published in 1800, Brettell credits it with improving the status of that practice by presenting: "an aesthetic, intellectual, and moral argument for the primacy of landscape over figure painting" Regretfully, it has yet to be translated into English.

A spectacular eruption of Mt. Vesuvius

I really like this simple arrangement of planes

But then. I also like this atmospheric cityscape

This is one of the history/mythology landscapes that looks pretty good.

It makes me want to be there.

another severe and great cityscape

Rather gritty.

Could have been done in America in the 1930's

some especially dramatic clouds

Valenciennes must have been thinking of Rembrandt's Three Trees

The Louvre showed both of these images on the same page without explanation.

One must be an altered copy of the other - but God knows what Valenciennes was thinking.

Corot, Castel Sant' Angelo Rome, 1826

Rousseau, Landscape after Storm, 1835

Following Valenciennes and his students, came the generation of 1830, led by Corot and Rousseau who

"injected both patriotism and realism into landscape painting. and "by 1850 had joined the aging Ingres and Delocroix as the principal painters of France"

The two pieces shown above are my favorites of those artists' work from about that time - though it must be noted that Corot was painting Italy, not France, while Rousseau's landscape appears more romantic than realistic. We might also note that Valenciennes' plein aire paintings were realistic depictions of the French countryside. And then we might note that Corot became more dreamy, nostalgic, and neo classical as he aged - while Rousseau's views became more simple and fierce.

Daubigny, La vanne d'Optevoz , 1859

Boudin, 1860

Brettell declares Boudin and Daubigny to be a bridge to the landscapes of Monet, Pissarro, Renoir, and Sisley that emerged in the mid 1860's. (he also declares them to be "lesser talents" than Corot and Rousseau - though he may be speaking for the literature rather than his own judgment)

He then remarks on the rarity of major exhibitions covering this French landscape painting before the Impressionists: there had been nothing in America since "Barbizon Revisited" in 1962, or any |"internationally significant exhibition devoted to the careers of Valenciennes, Corot, Rousseau, Boudin, or Daubigny in the past generation"

Corot, Festival of Pan, 1855-60

"The thesis of the exhibition - that Impressionist landscape painting developed logically from a well established tradition might seem more radical than it is simply because it has never been clearly demonstrated in exhibition form"

I doubt whether such logic can be proven - or even well stated - but we'll wait to see how Champa states his thesis for this exhibition.

"There can be little doubt that the central figure of nineteenth century French landscape painting was Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot"

Brettell supports this assertion by pointing towards Corot's reputation, decades of teaching, and prolific output - while noting that much of that output is now recognized as forgeries. ( One of those forgeries is examined here ) Alfred Barr even extends that influence into the twentieth century - while giving no mention of Monet at all.

Much as I love Corot - both his early plein-aire and later nostalgic visions - I can easily imagine that Monet and company never needed to see his work to do what they did. But maybe Brettell or Champa will offer further arguments.

"There can be little doubt that Corot was the only great painter active in the first half of the nineteenth century who combined the theories and methods of Vaenciennes with an intense analysis of the French landscape itself"

Congruent with making/seeing was the opposition of nature/unity. The subject was nature - the artist strove for unity - though nature might be considered as already possessing a unity of geology, natural history, and human history. Some notion of formal unity seems to be lurking in the background, but Brettell never makes it explicit.

Henriet came close when he wrote : "Painting after nature will not work without an extreme tension of the painter's faculties. It is a sort of hand-to-hand combat in which the vivacity of the eye and the rapidity of the movement decide the success". But regretfully, Henriet focused on the tension in the painter's faculties - rather than within the painting itself.

***********************

As Brettell indicates -- the big issue in this exhibition, as well as others that focus on the Impressionists - is to what extent were the Impressionists breaking new ground - and to what extent were they continuing a multi-generational tradition of plein aire painting.

I've lived with their predecessors, the Barbizon School, ever since I first entered the art museums of Cincinnati. Local collectors were strongly attracted to them over a hundred years ago. And I am attracted to them as well.

But still I think the Impressionists were up to something quite different. Their paintings are more experiencing a place in real time - a flashing moment of now. The earlier landscape painters seem to be more about cherishing a memory of something timeless.

But perhaps the rest of this book will change my mind -- we'll have to wait and see.

*************************************************************************

INTRODUCTION BY KERMIT CHAMPA

*************************************************************************

Constable, Dedham Lock and Mill, 1820

And now - amazingly enough -- Kermit Champa, the curator for this exhibition, immediately and emphatically distances himself from the notion of historical development proposed in Brettell's introduction, presented just before his.

The present exhibition employs a very different strategy from that of Barbizon Revisited, which stressed the aspects of historical development that were presumed to be demonstrable stylistically and sociopolitically across the course of fifty years of French landscape painting. The cumulative aesthetic effect of working from nature and the linking "of this practice to the advancing pressures for liberal political reform gave Barbizon Revisited - both as an exhibition and a catalogue - a distinctly evolutionary prospect. In fact, an evolution-revolution ideology was clearly in force. Today the notion of inevitable forward progress, inflexibly conceived, seems inadequate to explain the complex, sometimes forward, sometimes backward, often halting movement of landscape imaging that appears in the work of the three key founding figures of early- and mid-nineteenth-century French landscape painting : Camille Corot, Theodore Rousseau, and Jean-Francois Millet. It is very difficult to see their work "advancing" - changing, perhaps, but not necessarily moving cumulatively toward a ·point where the Impressionism of Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro becomes an evident next step, and a largely predetermined one at that.

Exactly my opinion! But it utterly contradicts Brettell:

The thesis of the exhibition - that Impressionist landscape painting developed logically from a well established tradition might seem more radical than it is simply because it has never been clearly demonstrated in exhibition form.

And Champa contradicts Brettell again, regarding that prior exhibition, "Barbizon Revisited".

The impact of Constable's work in Paris between 1824 and 1830 has been much studied... the problem is that French landscape work, when it appears with any frequency, doesn't look very much like Constable's, either in what it images or in its technical manner of imaging - his handling of light as reproduced by a palette that moves rapidly between large scale light and dark contrasts and through innumerable steps in values of reds, greens, and grays that climax frequently on the upper end of the value scale in pure or nearly pure white"

A rare exception apparently being the large Rousseau piece shown above - except that it is now a darkened ruin - even if it was famous in its day. It's a bit perverse to present it as an example of anything.

For a variety of reasons, many of which can only be suggested here, Constable's example was in large part a negative one for French landscape painting in the 183os. The apparent materialism that informed (or seemed to inform) Constable's vision had too much of science about it to allow any degree or form of sentiment. Seen from the vantage point of important French landscape work of the 1830s, it is clear that Constable's painting looked too materially complete in its determined accounting of natural appearance to have any expressive space or time left for natural sentiment. Or to put the matter differently, Constable seems to have seen nature without feeling anything beyond the sensation of seeing. More a scientist (which is to say a disinterested observer) than an artist in French eyes during the 183os, Constable's example required secondary processing by an artist like Delacroix to make it aesthetically approachable. Constable could be admired for painting landscape on a comparatively large scale in a fresh and unconventional way, but at the same time his work had to be recognized as a problematic example of what landscape painting without a "poetic" intelligence behind it, guiding it, might become. In its transcriptive brilliance, Constable's landscape expression could be comprehended technically but not as a language form or replacement for such, or at least not in France in 1830.

.

These assertions about the French reception of Constable seem possible - but Champa does not confirm them with any French text from that period.

Corot's justly celebrated outdoor oil sketches from the late 1820's (in Italy) and early 1830s (in France) suggest precisely the degree to which Constable's example could be let to operate by a gifted but cautious French landscape painter. These 'sketches or notes from nature demonstrate. a breadth of' technical means and a sensitivity to uniform lightness that sets them apart from the similarly informal works of Corot's immediate predecessors in France - Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes and Jean-Victor Bertin, for example. However, their lightness is carefully adjusted in value toward prevailing tonalities centering in beiges and light greens or blues, so that the disruptive sculptural impetus of Constable's whites never appears. Even in the most incidental seeming of Corot's sketches, the fusing of light and color toward relatively even values and often very close hues suggests that mediating "poetic values" are in force in a comprehensive way - Corot is seeing as he is comfortable seeing, or as it feels to him most poetically gratifying or productive to see. Yet, in his at least graded response to Constable, there is some confirmation of the latter 's effect albeit an inconclusive one.

Champa did not provide any examples of Corot to substantiate his argument - so I dug up two from the Met. Perhaps I should have kept searching, because these pieces seem no closer to the Constable shown above than do the landscape sketches of Valenciennes.

"It was the first time perhaps that one felt the freshness, that one saw a luxuriant, verdant nature, without blackness, crudity or mannerism."... Paul Huet

The above quote is pulled from Patrick Noon's "Crossing the Channel: British and French painting in the age of Romanticism" - an exhibition catalog that came out in 2003, about ten years later.

Champa relates the landscape painting of this era to Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Naturalism - as well as some notion of "poetic sentiment" (in contrast to a more literal scientific response to nature)

"There seems to have been in the 1830's a concentrated effort to establish what a modern 'poetic' landscape painting might or ought to look like. The issue here is definitely not one of naturalism per se but rather of poetic imaging based on nature (but no bound by it) visually and existentially.

Regretfully, he provides no period quotes to confirm this "poetic" effort - but he does suggest that Theodore Rousseau would have an anthropomorphic poetic sentiment in the following piece:

With its emphasis on a shaky footbridge, it does seem to be telling the story of a hazardous journey. The Frick Museum suggests that the artist hired another artist to paint in some figures to enhance that suggestion - and I do think the piece would be far better off without them.

Then Champa suggests that Corot would have felt such a sentiment from this piece:

The owner of this painting, the MFA Boston, tells us that "Although most of Claude's paintings included biblical or classical themes, their true subject was the light, atmosphere, and poetic mood of the natural world."

But the size, quantity, and arrangement of these figures make this piece feel like an exception.

Regarding this conflation of literature and painting, Champa refers us to a long essay in the Art Bulletin of 1940: Ut Pictura Poesis: The Humanistic Theory of Painting by Rensselaer W. Lee ( it now appears online at JSTOR. ) It appears to me that Modernist painting theory would reject this conflation just as firmly as Diderot had accepted it

For reasons which will be described at a later point in this essay, Corot and Rousseau seem at least to have entertained provisionally an ambition to organize feeling (or sentiment) via landscape imaging in such a way as to permit relatively free sensation rather than just word-fixed poetry to guide them. They appear to have done so because other experiences, namely musical ones, encouraged tentative probings in search of a truly free expressive space for painting, particularly nature-based painting - the sort of painting to which both were firmly committed. Increasingly, as the decades of the 1830s, '40s, and '50s unfolded, the feeling of seeing and the open-ended communicative potential of that feeling fascinated them. To paint from that feeling, without abandoning totally feelings presealed in poetic language, became the mature pictorial enterprise of both artists. The feeling of seeing would be left free to operate wherever and whenever word-based feeling reached its communicative outer limits.

Compared with his 1835 "Landscape after a storm", this does indeed seem far less concerned with a narrative. The tension is between the anarchy of nature and the graphic orderliness of painting.

But Corot seems to have gone in the opposite direction over time- with the naturalistic pieces coming earlier in his career, and the mytho-arcadian fantasies coming later.

Champa, however, considers those silvery, humid, atmospheric pieces to be more like music than narrative literature -- as he will explain below:

The late 184os and 185os are a period in which the landscape imaging of both Corot and Rousseau achieves whatever degree of distinction, confidence, and range it will ever have. This is the period when Corot can be seen to "finish" his sketches from nature - with a visual and chromatic complexity and subtlety that make them more than studies. Although Corot never emphasized value contrast, a considerable amount of hue variation develops in many of his sketches, giving them a completely different character from that found in comparable work from the early 1830s. At La Rochelle in 1851 he executes an entire monumental landscape painting (not a sketch) with constant reference to the motif in stable natural light.

Detail of above

More shimmering and whimsical - while less fierce than his earlier sketches.

Then in the mid-185os the works by which he is best known begin to appear : those consisting of superimposed veils of trees, water, wet atmosphere, and small strips of land with everything made to move or to hold still in response to idyllic figures or groups of figures strategically positioned. It is these works by Corot that contain most overtly his creative modeling of landscape painting on musical expression. In them he develops and deploys a visual language based -like dramatic music's audible language - on rhythms , harmonies, contrasts of accent, graphic-coloristic counterpoint, and ultimately on cadence. Corot's imaging of landscape finds its language space located at some midpoint between topographical description and strictly pictorial techniques of order and emphasis derived from (or modeled on) dramatic music. Narration is totally absent both in fact and in principle.

Champa admits that neither Rousseau nor Corot ever wrote about music in connection with their painting --- so the only documentation comes from their early biographers - and it is far more suggestive than explicit.

What ultimately replaces narrative in Corot's manner of landscape imaging is "touch," which is to say the intricately variable woven trail of his brush over, the various parts of a painting, acting either with or against the figures to determine the pace of the viewing eye. "Touch" for Corot is the ultimate (which is to say, final) imaging maneuver; it consolidates feeling that began in drawing and proceeded through tone and motific order. That which is most focusing of sentiment in Corot's best-known and most autographic work is "touch." It is the aspect of technique foregrounded as "touch" with which he is most comfortable. In all of his recorded comments on how a painting ought to develop, "touch" is featured as the "last touch," the orchestration, so to speak, of the pictorial effort. And, indeed, "touch" is a technical property exclusive to painting; its emphasis is ultimately what makes Corot a modern painter. However, the active presence of touch develops in response to (and is controlled by) an increasingly passive mode of landscape imaging. This passiveness is also controlled by the descriptively elusive non-painting model of music. Here is where the submissiveness and the gentility of Corot's art resides - in the roughness of backgrounding of all nature-based sensation.

Champa has taken us from musical qualities to what he calls "touch", and though he greatly expands upon it in a long footnote, he never offers a specific example of its absence - though he does note that

"An archetypal (almost mythical) severity of aspect marks Rousseau's manner of imaging; consonant with this is his self-removal (in terms of visible "free" painter's touch) from his finished work."

Apparently, Champa would consider these dabs and strokes of paint to be non-expressive facts that reveal details of subject matter but nothing about the artist. While I would say that they are no less personally expressive than the marks made by Corot -- even if they do express a less dreamy kind of experience.

The notion of "pace" in this instance introduces of the most problematic features of mid century imaging practice . Whether speaking of Corot, Rousseau, or Courbet from the perspective of musical modeling, there is no avoiding a description (however provisional) of the strategies aimed at extending spectating time. What this means is that all three artists must be seen to be inhibiting a "fast" reading of their work by delivering pictorial information in steps or, better, by degree. It could certainly be hypothesized that by doing so each artist was courting a music-type extension of spectating attention time, although in Courbet the extension can be seen as reading-type as well as music-type. Painting's traditional bondage to the fixed moment is clearly under attack here.

As an alternative theory,

I would propose that nothing repeatedly extends my "spectating time"

other than formal density. (after the curiosity regarding subject matter has been satisfied)

It is not the implied act of touching that makes the difference,

but rather how the resulting marks affect overall form

In Corot both the pace of touch and the leftright, front-back oscillations of the increments composing the landscape force the spectator to process the image rather slowly and from various directions, and the processing is rarely conclusive enough to deposit a clear "picture" of the "painting" in the spectator's memory. Corot thematizes this in his well-known late (post-186o) paintings of women models in his studio, shown either studying a landscape displayed on the easel or turning away to muse on that experience (perhaps before turning back to undergo it again) . Usually the model is posed holding a mandolin, suggesting that her spectatorship proceeds from music to painting and back to music

.What a curious painting.

You look at the woman; the woman looks at the painting; and the dog looks at both her and you.

Possibly an update on Dutch interiors that also included women, musicians, and paintings on the wall. But this is clearly in the artist's studio, and the woman is a costumed model, not a hausfrau.

This is art about making art.

Millet, Going to Work, 1851-3

Unlike Brettell, Champa puts Millet into the story of French landscape, even though he was mostly a figurative painter.

Millet: Pasture near Cherbourg, 1871

When speaking of Rousseau in the 1850s, it is irresponsible to ignore the fact that, as an artist, he was not nearly so communicative with and reactive to Corot as he was to the non-landscape painter Millet. Conversely, it is irresponsible to view Millet's nominally figural, peasant paintings as being non-conversant with Rousseau's landscapes. Before his move to Rousseau's domain, Barbizon, Millet had been a comparatively ordinary, although talented, painter of portraits and quasi-eighteenth-century erotiques. His shift of aesthetic strategy in the direction of the peasant (or peasants) in situ was a radical one - not as radical perhaps as would have been a shift to straight landscape painting, but radical nonetheless. What, one wonders, drew Millet to Barbizon and to Rousseau? And what, ultimately, was there of importance in Millet's presence to the development of Rousseau's landscapes of the 1850s?

None of the above is self evident to me- so we'll wait to see how Champa further explains it. Both Millet and Corot seem to mythologize peasant life, while Rousseau seems more like a naturalist than either one.

The somewhat confusing relationship between Rousseau and Millet at Barbizon must be considered aesthetically and ideologically in terms of inherently conflicting paradigms - a musical one for Rousseau, a literary one for Millet.

Traditionally (in terms of criticism and scholarship) , Millet has been set slightly apart from not only Carat but also Rousseau because of his "classical literacy. " While the point has never been developed in any depth, Millet has been viewed as a reader and his associates as some other species. Here we have referred to that other species as "melomane" - something which Millet was perhaps less likely to have been, since his provincial Norman childhood had been limited artistically (in a potentially problematic way) by his father 's occupation as a choirmaster. The excitements of literature would come later. Even though Millet kept certain of his father 's original manuscripts (musical ones) in his possession throughout his life, there is no evidence to indicate that· music per se was anything much more than a provincial memory for Millet to subvert in order to exercise his own creativity. Neither Rousseau nor Corot had music in the family, but Millet did, so he was clearly not prone to being "liberated" or inspired by it to the same degree. He needed the "headier" stuff of classical poetry, having grown up with music as a probably rather oppressive constant. Carat and Rousseau, on the other hand, grew up in the Parisian world of custom tailoring and draper~-making. Each of their mothers had a fine eye for colors and materials which most likely encouraged their aesthetic efforts at first, but limited the originality of those efforts. Ultimately both needed the complex stuff of music to get loose from what they had been accustomed to knowing as tasteful. The somewhat confusing relationship between Rousseau and Millet at Barbizon must be considered aesthetically and ideologically in terms of inherently conflicting paradigms - a musical one for Rousseau, a literary one for Millet.

The issue of difference resides, in the final analysis, between a pictorial musicality developed incrementally (through separate voicings) in Rousseau and Millet, and one conceived more symphonically as a seamless whole characterized more generally in Corot. In either instance the pictorial language space is musically modeled, but the discourse within that space begins from different points and proceeds to different visual conclusions.

Considering the above, it is not surprising that the art of the Japanese woodblock print would become very nearly an obsessive fascination of Rousseau's and Millet's in the 186os. Its voicings (or its visual sounds) were even clearer and more distinct than their own, and even more musical in both graphic and coloristic idiosyncrasy. A nature- based art, although superficially different from theirs, it was actually identical to theirs on its deepest linguistic levels, and they could not fail to recognize the similarities and to celebrate them in terms of collecting, if not in direct pictorial emulation. Only minor indications of a Japanese graphic web, proceeding decoratively, appear in Rousseau's paintings of the mid-186os, and only superficial gestures

In the work of both artists (Rousseau and Millet) in the 1850's, there is a strong sense of drama far more portentous in its feeling than what can actually be seen happening among its nameable components. Rocks, trees, working or praying peasants become "voicings" manipulated for dramatic effect by position and counterposition, by rhythmical or arrhythmical visual connections, by color and light. Ultimately, the voicings resolve into something like a musical cadence which at a perceptually fixed point collects and concludes what has been deployed fragmentarily. The effect of all this has something related to narrative about it, but the internal components are not specific enough to make the narrative truly comprehensive. Yes, there is a degree, or rather there are varying degrees, of "being toldness" operative, but there is a far stronger opposing sense of the unspeakable.

Monet, Corner of the Studio, 1861

For Rousseau and Millet, the recognition of the qualities particular to Japanese art confirmed their own pictorial operations rather than modified them. The case would be different with the great landscape newcomer of the next generation, Claude Monet, who would quite literally begin from Japan and not because of sentiments grounded in the experience of nature but rather because of a primal excitement experienced in shaped and painted color. In an early painting of the corner of his studio from 1861, Monet would oppose an 1850s-type landscape in the upper-right-hand corner with a boldly patterned and brightly colored oriental carpet on the floor. Outlandishly florid wallpaper connects the wall to the floor, and in front of it is Monet's paint box and palette, loaded with pure color and white straight from the tube. A clearer statement of what his art was destined to be about, and what it was to supersede expressively, could hardly be imagined.

In Rousseau, Millet, and Corot, Champa sees a musicality: an "anti narrative force" in opposition to subject matter. And in Monet, even more so - as inspired by the Ukiyo-e Japanese prints then so fashionable. I can't identify the landscape painting-within-a-painting in the upper-right corner shown above - but it could be Rousseau - or young Monet himself - and it seems no less musical than the rest of this piece. This "clear statement" comes from Champa, not the artist.

I'm agreeing that "The Corner of the Studio" echoes Japanese prints - but throughout his career Monet would echo various other styles as well, from Watteau to Cezanne and Seurat.

**************

COURBET AND THE ANTI-MUSICAL

Wouldn't the above landscape be appropriate for the powerful symphonies of Anton Bruckner? He was another village boy of nearly the same age who also did good in the big city. So it's not that Courbet was anti-musical -- his music was just radically different. He was replicating the inner energy of nature more than creating a vision of nature as a peaceful retreat: to frolic, explore, or contemplate. With its Taoist philosophy, traditional Asia brush painting is often more successful at using the one to give us the other.

Champa did not offer any examples of Courbet landscapes - so I selected the one shown above. For me, his work is more admirable than enjoyable.

Xia Chang (1388-1470), Bamboo covered stream in spring rain, 1441

A frozen moment.

Surprisingly, still fresh and alive.

- much more than feeling like a bold man from Franche-Comte.

Courbet seems consciously to choose not to evoke the "look" of painting or to open his images to sentiment. His works are emotionally closed doors which seem to offer only appearance. That appearance is at once momentary and·dead. The particular moment of a Courbet has happened; it is over as soon as it is painted. The imaging comes and goes before it has been interrogated by feeling and sorted for ideas. But nothing is unsorted either; no ambiguities except "real" ones intrude. What Courbet manages by proceeding the way he does - besides annihilating both narrative structure and musicality - is to call an unexpectedly high degree of attention to his act of choice both in terms of what to paint and how to paint. The operation of his imaging virtually becomes his subject. Into what seems an ego-denying activity of description, Courbet implants an ego asserting activity of aggressive and technically personalized pictorial construction - one that bonds the senses of vision and touch into a patchwork of weighty paint marks that slip back and forth in the forces of their address to one or another sense. This touch (wholly unlike Carat's rhythmical weave) moves between the only partly connected deposits of the brush, the palette knife, and the sponge. Its activity and its material life replace the deadness, or at least the pastness, of the depicted image as Courbet's "real" content. Painting is the materially live event, and technique is what there is to be seen and responded to after the comparatively simple activity of subject recognition has happened.

That's one way to put it - if we're going to distinguish deadness of form from deadness of compassionate response.

Another way would be to say that Courbet is confrontational. Surprise or shock or discomfort are the sentiments/emotions his paintings provoke --- while questions like "what is nature?" or "what is society" are ideas they evoke.

Courbet, Rock of the Hautpierre, 1869

Here are two Courbet's now hanging at the Art Institute. What strikes me is the confrontation with a discrete, single subject: a big mountainous rock or the proprietress of a brothel. They are not about ambience or ambivalence or mood or ideal.

Delacroix, Traveling Arabs, 1855

To find anything remotely comparable to Courbet's self objectification in his painted constructions, one has to look momentarily away from developments in French landscape painting and consider instead the late (post 1848) work of Eugene Delacroix.

Without undertaking to treat this in detail, it is necessary at least to point out the considerable number of mediumsized paintings Delacroix produced for sale by private dealers, many of whom already handled works by Corot, Rousseau, and Millet. The kinds of paintings Delacroix produced for the gallery market were, for the most part, far less complexly literary in their subject matter than was the norm for his Salon work. Lion hunts, tiger hunts, iconographically uncomplicated pictures of wandering Arab horsemen these works showed Delacroix acting as a comparatively "pure" or non-literary painter. The viewer is given little to think about, but a good deal to look at - intricate tapestries of color, a

kind of color that moves rapidly up and down the chromatic scale carried by continuously animated graphic rhythms and an extraordinarily rich (materially) surface construction of paint. Rather like Courbet's work, these paintings by Delacroix ingest their enormous historical painting culture - a culture consisting of Rubens, Veronese, Titian, and, increasingly, Rembrandt. The often precisely quotative art-historical character of Delacroix's official art, with its perfect calibration of traditionally licensed technical effects carefully bonded to the requirements of dramatic narration, is no longer in evidence in his gallery-market works, as technique per se begins to appear the source for generating strictly personal expressive impulses that derive from the artist's most private emotions.

Delacroix, Lion Hunt, 1855

Champa provides an image of "The Arab Travellers" as an example. For me, "The Lion Hunters" is much more compelling as a "continuously animated graphic rhythm" and exciting use of color. And this viewer does indeed think about nothing other than the visuality of it. (even though the surface textures of the paint cannot be seen in reproductions)

I would love to have Champa explain why he thinks Rembrandt was a growing concern for Delacroix- as well as specify what he took from Rubens, Veronese, and Titian. Mostly, I see the dynamics and sensuality of Rubens in this work - but then even Wikipedia mentions that connection - and the job of art historians is to say something new.

Rubens: Lion, Tiger, and Leopard Hunt, 1615

Why does Champa tell that these paintings are a "strictly personal expressive impulses that derive from the artist's most private emotions" - except perhaps in comparison with an earlier Delacroix like this one that makes a political statement:

But then, Champa has told us that Courbet was also making personal expressive impulses, and that makes no sense to me either.

Both artists are connecting us to the power of the natural world of lions, mountains, and crashing water. How personal is that ?

As with Courbet, Delacroix's expression becomes increasingly identified with his technique. It is selfimpassioned as is Courbet's, and through the 185os the works of one master come to facilitate the eventual acceptance and understanding of the "technique as bearer of content" of the other. What is most interesting in all this is the increasing momentum of the phenomenon of freestanding pictorial technique. This phenomenon becomes virtually the rule of the most important French painting of the mid- and late-185os. That it is musically emulative in Corot,"reality" emulative in Courbet, and residually exotic in Delacroix makes very little difference. Ideological similarities of expressive and constructive practice increasingly outweigh differences in the nominal subject origins of such practices. In the emerging consensus of aesthetic opinion regarding the self-sufficiency of technique, the musical model for painting metamorphoses from one of recognized emulation to one of essence. Musicality has become intrinsic to significant pictorial practice to the degree that its ideological functioning need no longer even be recognized verbally. In spite of the fact that he painted Berlioz's portrait, Courbet would never have granted that his works, particularly his landscapes, were informed by concert music, but they were nonetheless - at least in the terms advanced and developed in the present discussion. On the other hand, Delacroix's melodrama can be thoroughly documented from entries in his journal over as long (or even longer) a period of time a Corot's.

Which mid-nineteenth century art critic might exemplify that "emerging consensus of technique”?. By "technique" did they mean that procedure which is used to create any effect other than ideological?

If I might digress into a brief discussion of the word "technique", I would like to separate it from any notion of interpretation or expression or inspiration or mimesis or formal energy -- and restrict it to the kind of procedures that could be written down in something like a technical manual.

Might we look instead for an "emerging consensus of the aesthetic"- and exemplify it with Walter Pater (1839 - 1894), an art critic who, unlike Denis Diderot, would never ask whether a painting presented the image of the subject as the critic himself would like to imagine it.

Though I don't see it in his landscapes, "self objectification" does appear to be the primary theme in this large painting. Champa likens the paintbrush of the artist to the baton of an orchestra's conductor who, in this case, is also the composer. Champa reminds us of the context in which the painting was first shown: Courbet's own "Realist Pavilion" in the first Parisian Universal Exposition. What is most real, here, is the artist's own self promotion - though we may notice that the artist is conducting "a landscape painting, which, like a piece of music, is being composed and performed indoors even though it is ostensibly about nature in its "real" appearance. If The Studio is truly an allegory, of what is it allegorical? Is it perhaps too glib to suggest that it is about defining painting (rather than architecture) as silent music? It does seem to be at least partly about that; however, what it seems more about is the complexity of the strategy of pictorial making, Realist or otherwise. A theatricalized tour de force of painting's enterprise, where memory and technique and genius combine into an expression-laden paint construction - this seems more completely to account for The Studio's appearance. The central position of landscape painting (whether generic or specific makes little difference) in The Studio signals something of the radical status Courbet granted to the practice of the freely natural image, as opposed to the traditional figurative one. Landscape practice stands almost as a signboard of modernity in the foreground of The Studio. It echoes through the faint images on the rear walls, making the entirety of the picture space alive with reverberations of the cadence of landscape "making." Courbet pictures\ himself producing nature in The Studio, making painting like music in what it "really" does, rather than in what it emulates musics- having done. Courbet is effectively setting landscape painting in music's position as a source of nature rather than an imitation of it or an outgrowth of it. This positioning of landscape painting is where Courbet's sublimation of the repressed musical model operates. In addition to everything else, then, The Studio as a whole enacts Courbet's sublimation of a force (music) which he cannot accept ideologically but which nonetheless is called upon to define allegorically his highest sense of the mission of pictorial artistry. Courbet presents landscape painting as having risen to the challenge of music by theatrically signaling a parity. This is rather like Berlioz's epochal assertion that dramatic music had achieved and perhaps even eclipsed the expressive level of poetry!"

Is it Courbet’s "repressed musical model" , "anti-musical musicality", and "concert of silence" —- or is Champa just trying to pound the square peg into the round hole while craving for paradox? "The Studio" is nearly twenty feet long. It’s less like an imaginative vision, and more like a tableaux vivant of actual people and objects in a room with the viewer. The "Realist Pavilion" would have been more like a wax museum than an art museum, and the producer would have been more like an entertainer than a mytho-poetic artist of the French Academy.

It’s too large for me to guess at it’s aesthetic impact on the basis of computer screen sized reproductions. The space does feel dark and murky - while the artist’s dynamic act of painting is the center of attention. His subjects are the ordinary people in front of him - his supporters are the wealthy or learned people behind him. Is this the first painting to assert the artist’s identity as a leader of an avant-garde ? ( the Tate Museum’s website identifies Courbet as the first such artist). He is a hero to young boys, playful dogs, and full-bodied young women without clothes.

One might note that Courbet was indeed in the avant garde of an army of realist painters - especially in Russia. Today's avant garde are no less provocative, but they may be closer to the end than the beginning of those who march in the same direction. Dada has just celebrated its 100th birthday.

A long footnote reminds us that "No single nineteenth century painting has had more critical / documentary attention over the past three decades than "The Studio"". Champa, and others, call it "an allegory of allegory" - which does seem more like a very post-modern idea. Michael Driskel, on the other hand, likens it more to the popular culture of that time: a circus, popular theater, or even a parade. That makes more sense.

Champa goes on to make even a greater claim for this painting:

Pre-1855 French landscape practice is involved above all with the formation of an irnaging language. Post-1855 practice features exploration and _conjecture, sometimes advancing, sometimes attacking norms only recently established.

The differences between Corot, Rousseau, Millet, and Daubigny might suggest that they were also explorers in search of their own language of imaging. While The Met's online essay, "The Transformation of Landscape Painting in France" doesn't even mention Courbet at all.

But Champa develops his argument, making it more convincing:

Working with continuous visual access to a particular natural motif, the paint construction seems progressively to loosen and become more varied. The color (both in terms of hue and value range) becomes less predictable and more driven . by the excitement of discovery. Different kinds of landscape motifs increasingly demand different graphings - different balances of emphasis on touch, and on the blocking and massing of increasingly bright color. Color becomes daylight-informed rather than painting-informed, and it becomes so in more and more extreme ways. There were certainly precedents in the work of Corot, Courbet, and Rousseau for certain daylight models for painted color, but, generally speaking, one model eventually became the chosen norm in the work of each artist.

All of this changes after 1855. Non-normative and changeable daylight is painted, and it is painted differently by each individual artist and within the personal oeuvre of each. Jongkind, in particular, explores an almost uncontrollably wide range of nature-based exercises of color and touch. Daubigny tends more to refine his construction within a comparatively narrow range of exercises, while Boudin alternates between elaborately woven, somewhat stormy tonalities and vigorously pure color-accented ones, developed with a very patchy, at times almost random, touch.

Apparently space did not allow Champa to elaborate on those examples of landscape artists who achieved one language of imaging - and then searched for another again and again. Claude Monet was like that - but he was only 15 years old in 1855.

These two pieces do feel as different as Monet does from Van Ruysdael.

His other two examples, however, are less convincing. If Daubigny only "refined his construction within a comparatively narrow range of exercises" he was hardly influenced by anyone after 1855. While Boudin was only beginning his career in that year ( age 31 ) and there are very few examples of his prior work.. His later paintings eventually became quite lively and loose, as Champa describes them , though as seen below, 1855 did not seem to be a turning point.

Champa then shows us these two pieces which do indeed appear to respond to Courbet's "The Studio".

But how do they contribute to "The Rise of Landscape Painting in France" ? There are elements of landscape within them, but they are so much more about figurative painting and its history.

By the way, he also notes that they closely follow the 1861 Paris premier of Wagner's Tannhauser with all of its scandalous, sensational contrast of piety and eroticism. But we may note that despite its extensive revision and 164 rehearsals, it was received so poorly that it closed after three performances.

Manet's strategy with Courbet's respected precedent was much the same. In two paintings done around the same time (1862-1863), Dejeuner sur l'herbe and the Old Musician , Manet took Courbet's (theatrically autobiographical) Studio apart and reassembled it differently in two paintings. Courbet's allegory was already intricate and ambiguous. Manet made it impenetrable but technically (in terms of color and paint structure) attractive - sensuously, even luxuriously so. The eye was enabled to proceed uninhibitedly while the mind was made to stumble over the character of Manet's subjects their "idea" and their meaning with reference to the technique of their presentation. His Old Musician sits in Courbet's own Studio position, but he stares at the spectator, seeming to ask what to do with his material (the figures around him). Manet's nude model in the Dejeuner sees (and challenges) the spectator of the painting at the moment the spectator sees her. Her looking out and her reason for being where she is - undressed, sitting with two dressed men (who are doing nothing) in a landscape- are irrevocably disconnected whether considered in terms of reality or of allegory. As contemporary viewers were somewhat slow to see, her puzzling existence is art historically referenced through a combination of quotations from Giorgione (the Concert champetre) and Raphael (a river god grouping engraved by Marcantonio Raimondi). But reference is not explanation, and, even made aware of references, the viewer has about as much access to her as a knowledge of Beethoven provides for understanding Wagner. The point here is that quotations and references don't account for the sensuous effects, and the fact that they fail to do so (even as they are recognized) is what, in both Wagner and Manet, delivers sensuously manipulated techniques so powerfully - or, from the contemporary audience's viewpoint, so scandalously.

So if we acknowledge that Courbet's "The Studio" is an allegory of allegory, these two Manet's may be figurative paintings about figurative painting. They are not about the natural, political, or spiritual world at all - other than to suggest that the artist - and his fellow urban sophisticates - have chosen to ignore it. The paintings look good because both Courbet and Manet had immersed themselves in the old masters, especially Velasquez. Fifty years later, Duchamps would take the project significantly further by ignoring the old master tradition as well. The Duchamps tradition is now still going strong a hundred years later. It is the mainstream of contemporary art - and distinctly antithetical to landscape painting. If "The Studio" confirmed the importance of landscape painting in 1855, it also initiated it’s marginalization in the centuries to come.

The Wagner-Manet example provided unprecedentedly high standards of spectator excitation (or consternation)- standards with which every contemporary artist, in whatever medium, had to contend. There were really only two viable options: either the audience (critics included) could be comforted by the reinstatement of past aesthetic gentilities or the assault could be continued and even spread to different fronts. The rather surprising fact is that the latter option was acted upon most resolutely and effectively by landscape painters, in particular by Monet. He systematically absorbed and critiqued Manet as completely as Manet had Courbet. He progressively emptied out Manet's excitingly confusing imagery, substituting landscape motifs in its place. Intensely arbitrary coloristic complexity became his main excitational weapon.

Monet's colors are certainly more complex than Rousseau's -- but are well within the tradition of French painting. And actually -- if any French painter could depict Wagner's Tannhauser, it would have been Boucher.

They worked out of doors to find motifs which best supp;orted their search for emphatic effects, but they didn't paint what they saw so much as they used what they saw to paint as they wanted.

As they painted, what they saw themselves painting was informed as much by Japanese prints, Delacroix's palette, Manet's lusciously colored touch, and Courbet's plastic turbulence as it was by the visible nature that stood before them. In the foregrounding of paint structures simultaneously driven by prior artistry and experience of the moment, before the motif, both painters certainly kept clear in their minds the high contemporary standards of sensuous intensity which they had felt personally in the art of Manet, Courbet, Delacroix, and Japan and which they had witnessed secondhand in the near-mystical responses of their friends, Renoir, Bazille, Cezanne, and Fantin Latour, to the music of Wagner.

Theirs was to be the "new painting," not replacing the old in landscape practice, but opposing it with a new power and a new nerve.

So Champa proposes that late 19th Century French landscape painting is not really about the landscape of France. It's not a connection to the natural world, it's a forceful expression of self - as egocentric as Courbet's "The Studio". Does that really account for Monet's fascination with his water lily pond in the final decade of his life? Is Monet's "luscious touch" what makes it so special - or is it the feeling of being immersed in the watery miracle of life? Perhaps they are inseparable.

Forceful self expression is more evident in the landscapes of Matisse and other early Modernists. They have little sense of place. They are looking inward. - and the canonical narrative of Modernism abandons observational landscapes and plein air painting as it enters the twentieth century.

Artists and viewers, however, did not. Monet remains the focus for blockbuster museum exhibitions - and many good painters continue to emulate him. It's just that their preferences are of no concern to the academic world for which Champa was writing.

*******

Revisiting the Breitel introduction - Champa certainly would not agree with Breitel's central thesis:

"The thesis of the exhibition - that Impressionist landscape painting developed logically from a well established tradition might seem more radical than it is simply because it has never been clearly demonstrated in exhibition form"

Now I happen to believe that art history is more of an ongoing dialog based on current experience than an accumulation of proven fact and theory like the hard sciences. It's rather surprising to begin an exhibition catalog with two contradicting introductions that seem unaware of each other. But they are indeed complementary. One of them (Breitel) views the Impressionists in context of earlier landscape painters. The other (Champa) connects them to the perpetual avant garde inaugurated by the Salon des Refuses. Every period of history can, and should, be viewed by both past and future. Yet we might note that Champa is not especially concerned with landscape painting.

Champa presented some "Methodological Notes" at the conclusion of his essay. He reveals that the director of the museum which hosted this exhibition, the Currier Gallery, did not require him to "write an essay providing an account of all aspects and perspectives which in various ways informed French landscape developments". And that would be impossible anyway, wouldn't it ? Instead she commissioned introductory essays from two other scholars. Possibly she tolerated his "eccentric" approach because she was formerly a graduate student of his at Brown.

Champa then proceeds to offer some explanation for his "singular insistence on a "music" model". Given some free time, he would rather listen to music than read a book. Good for him! I would have preferred him to focus more on the paintings that we can see rather than the music that the artists may have heard. I found his musical analogies more whimsical than insightful about either the art or the music.

.

.

No comments:

Post a Comment