These are the first two Chapters of David Anfam’s "Abstract Expressionism",

first published in 1990, and revised in 2015.

**************

Jackson Pollock, Tondo, 1948 (detail)

Abstract Expressionism is a landmark in the general history of art and of modern art in particular. Like the Cubist epoch it represents a revolutionary event which revises our view of things before and after. Only in this case even the historical distance separating us from those early years of the last century is not yet available and what began with the rise of the movement shortly before the Second World War opens perspectives that enfold the present. In microcosm we might compare this to the far vaster shift which saw America itself command the centre of Western political power and culture after 1945. Together the two developments indeed thrust that country for the first time in history to the forefront of the visual arts, a sphere in which it had always traditionally either imitated Europe or followed its own eccentric patterns.

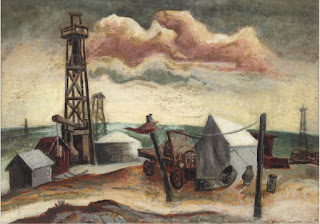

Landscapes and figure pieces done before about 1938

show Pollock, who was clearly always ill at ease with the third dimension, transforming Benton's scenarios. Crude surfaces together with a vigorous attack repeat his mentor's notion that such traits revealed directness and authenticity. But Camp with Oil Rig (c. 1930-33) and Going West (c. 1934-38) are already far from prototypes like Benton's Boomtown of 1928 and his other scenes of confident westward journeying. Life and colour are instead drained from the former with its props scattered over a desolate earth whose curvature becomes a tumult of all nature in Going West. Elsewhere throughout the early works this swirling upheaval draws the human presence or its surrogates into some greater overall rhythm.

That initial gloom is normally attributed to Pollock's admiration for the melancholy nineteenth-century American romantic Albert Pinkham Ryder, and the turbulence likewise attests to his studies after Mannerist and Baroque masters including El Greco and Rubens. However, Going West further suggests an awareness of Turner's Hannibal Crossing the Alps (1812) with its similarly prominent orb in the sky, driven figures, rocks and in particular a wrenching vortexlike organization. In the vortex Pollock probably saw a symbolic configuration keyed to his concern with polarities because its shape imposes wholeness upon chaotic energy, pulling outer limits towards an inward focus.

Philip Guston's first paintings located the disquiet in a political sphere. Coming from a family that had fled the Tsarist pogroms and soon drawn to socialism, like his fellow Jews Rothko and Siskind, Guston knew about oppression at large as well as the more local activities of the Ku Klux Klan (its membership reached five million in the 1920s) and other traumas in the Los Angeles of his youth, the flagrantly corrupt WASP-controlled metropolis that is the setting of Raymond Chandler's novels. The hooded armed protagonists in Guston's the Conspirators (1932) and his 1934 mural for the palace of the former emperor of Mexico, Maximilian, refer to kindred menaces. All the same, these paintings aspire to a breadth founded upon Italian Renaissance art, Picasso's ample Neoclassical manner and de Chirico's stark perspectives. Content and handling therefore coexist with some irony - since the average Social Realist would have pinpointed a more topical message. Indeed, the pencil study for the Conspirators showed a lynched black high up in the background. Instead, illustration is annulled as slyly as his hankering after a Grand Manner. We confront a figure scene without faces, drama without action and, as the hollow foreground element implies, volumes that are mere shells. Even the situation belongs as much to the props of the Hollywood studio.

Anfam presents a conventional view of art history - though he does suggest that historical distance is not yet available to confirm it. In my view, analytical Cubism was a cul-de-sac with enduring appeal only for those who respond to theory more than art. It was one of many provocative new approaches that had been arising with greater frequently in major European cities for decades. The higher reaches of the twentieth century art market responded well to eyesore provocation, and like the early examples of Cubism, Abstract Expressionism didn’t really look very good - in a radically different way.

But ABX was indeed a landmark, indeed a revolutionary turning point in American art - or at least the market for it. It’s not yet clear how Anfam determined who's in the "the forefront of the visual arts". Does he have any criteria other than auction results?

BTW - The painting shown above adorns the cover of the edition I’m reading. It’s still in private hands and a good reproduction cannot be found online. It seems so much more attractive than many Pollock’s I’ve seen in person. The struggle between resilience and despair has not yet been conceded. The gold and red lines may actually be beautiful.

Jackson Pollock photographed by Namuth, 1950

Mark Rothko, White Band (#27), 1954, 81 x 87 "

Willem DeKooning, Woman I, 1950-52, 75 x 58"

In the following text, Anfam presents the above three pieces as among "the most famous instances" of abstract expressionism. They certainly have large size in common - but we might note that the "Pollock" is not a painting at all - it’s a photograph of the artist working; the DeKooning is flagrantly figurative; and the Rothko is something like the inverse of action painting.

What they do have in common is a self-centered, personal angst - running from depressed to angry to disgusted to alienated. That is what sets them apart from the more global, even cosmic, abstract painting of the early modernists. In the high culture of postwar America, social and personal idealism became marginalized if not shunned. Pollock self destructed in 1956, but we may note that the work of the other two appreciably lightened up in the following decade.

American painting was dominated by the "serious, strange, and extreme" for only a few years, but the positive mimetic figurative art that it replaced has yet to bounce back - even seventy years later. That is the most enduring legacy of Abstract Expressionism.

Both changes took place with unusual speed and thoroughness, provoking many at times contradictory explanations, and are responsible for some of the more familiar cultural emblems of the sophisticated postwar West.

As Hollywood, Coke or a Ford soon became part of the everyday geography of experience, so the most famous instances of Abstract Expressionism have provided readymade symbols of modernity to our cosmopolitan eyes. Jackson Pollock's mazes of paintwork [I), Mark Rothko's hovering rectangles [6] and Willem de Kooning's strident Women [13] possess the same sort of currency as Piet Mondrian's grids, Picasso's multi-faceted faces or Warhol's Marilyns. It was in Toledo, Spain (not Ohio), that in the 1980s I saw a car patterned with 'Pollock' splatters (similar jeans and T-shirts are indeed long since left-overs from the 1970s) while Rothko could pin to the studio wall an urbane New Yorker magazine cartoon [2] showing 'sunsets' imitating his icons well within his own lifetime. Yet for all its cachet, Abstract Expressionism will probably never quite find the audience that embraces Impressionism nor the outright popularity enjoyed by Salvador Dali or Jeff Koons. For that it remains a shade too serious, strange and extreme, like Cubism itself.

Querying popular opinion does not seem the best path to understanding anything — unless no other path is available. Will Anfam ever offer one?

Norman Rockwell, Abstract and Concrete, 1962

Continuing in his theme of popular responses - Anfam shares this piece- telling us that:

Efforts to stereotype Pollock and buy extension the works of his colleagues started soon enough.—— A few are forthright like the 1962 Saturday Evening Post cover by Norman Rockwell. This reduces Pollock's delicate lines to a wall of splashes that leaves the dapper spectator cold.

Apparently Rockwell also painted that "wall of Splashes" separately, without any figures in front. I wish I could find it on the Internet. It’s definitely quite different from what Pollock would have done, perhaps intentionally so. Rockwell was not that dark and angry. Also - I see no evidence suggesting the dapper spectator does not appreciate the painting he is viewing. He certainly is respectfully giving it his complete attention. Rockwell’s design allows viewers to project their own narrative upon the scene - which is exactly what Anfam has done. I see it as a monumental floral. And we might remember that Pollock had died six years earlier - so Rockwell may have been paying his respects to a younger artist who died too soon -with a bouquet of flowers.

Disregard or hostility, however, continued with Tom Wolfe's 1975 satire The Painted Word which claimed that critics just injected meanings into the images and, perhaps more unexpectedly, with recent Marxist historians who perceive 'decomposition', 'alienation' and 'negation'. All these models are inclined to mistake actual themes - dynamism, chaos, space, traces of the human presence - for somehow involuntary or detrimental eruptions.

Plainly, Norman Rockwell's parody and Pollock's Lavender Mist (1950) attest to the difference

Jackson Pollock, Lavender Mist, 1950, 87 x 118"

I kinda like this one. It’s melancholy - like crumbled dry leaves decomposing on the pavement on a gray November day. Why can’t it be both thematic as well as an "involuntary eruption" ? Sometimes melancholy crosses over into despair and alienation - but I’m not feeling that here. Either way - it’s quite different from Rockwell’s abstraction _ which actually reminds me of what Jim Dine has been doing in recent years.

Anfam uses the rest of his introduction to query the list of Abstract Expressionists - but only as reputation would have it - so I will skip that discussion.

In Chapter Two, "Background and Early Work", the above is presented as an example of the optimism and impersonality against which the ABX artists were painting:

In painting Charles Sheeler had already treated such indigenous themes as Shaker architecture as early as 1917, employing clear geometric planes influenced by Cubism yet without its fragmenting lens. Over the next decade this immaculately sharp approach spread (including photography as well) and earnt the generic title of Precisionism. Nature rarely disrupts its often man-made but cold environment. Like most of Sheeler's works, Upper Deck (1929) is depopulated and its complex of svelte metallic elements evokes the certitudes of impersonality. Thus

far Precisionism was in step with much European art of the 1920s which presupposed few questions about the individual.

For just as the 'moderne' style of the time was meant to bring a clean, well-lit future to the present, so the large streamlined form would become a symbol of public confidence during America's Depression, whether in the sweep of locomotives, buildings or idealized landscapes.

Stuart Davis, Swing Landscape, 1938, 86 x 173 "

The abstract paintings of that period could be even more optimistic

But "impersonal" is not always the right word.

This is some kind of collective joy - a community celebration - much like Jacob Lawrence.

Barse Miller (1904-1973)

Here’s some cheerful work with figures and cityscape.

Squaresville, USA

The total inverse of those dark, ABX Bohemians.

Can’t guess why Anfam ignores this kind of thing.

Perhaps it’s because he’s British.

Thomas Hart Benton, City Activities with Dance Hall, 1931

Don’t know what to make of all this. Parody or celebration? Innocence or corruption? Idealist or cynic? Beautiful or ugly? Cheerful or depressing? So much hurly/burly energy spent being non-committal. I would never travel to see it.

Here’s Benton’s acrobat (1931) set beside Manship’s "Prometheus" at Rockefeller Center.

Carnival acrobat versus Classical hero.

I love Manship’s flying figure - and wish it was in Chicago’s Loop instead of the steel Picasso.

Though I do appreciate Benton’s cynicism about the American dream.

"Smoke - Your Health Demands It"

A commercialized public discourse full of dangerous lies.

I also appreciate the vignette of the reclining plutocrat offering a fistful of dollars to a scowling artist.

Benton was paid nothing for this mural made for the New School of Social Research - a refuge for leftist European scholars exiled by Fascism.

While Manship probably received a fine fee from John D. Rockefeller Jr.

But the beginnings of Abstract Expressionism took shape against both this optimism and another more negative vein which the Depression would intensify. Although America

championed material progress it remained a wasteland to those who preferred human and spiritual values. For expatriates like Ezra Pound it was ever 'a half-savage country, out of date' and Sinclair Lewis in Babbit (1922) satirized an emotionally barren American stereotype eventually known to the 1950s as 'the Organization Man'. Such disaffection was to be repeated by Clyfford Still, David Smith and others who noted America's sterility and alienation, a theme already current in literature from Eugene O'Neill's dramas to the novels of Hemingway and Scott Fitzgerald. In particular, William Faulkner's remarkable phase of literary experiment initiated by The Sound and The Fury in 1929 had a sombre inward tone which paralleled that of the Abstract Expressionists in combining realism with a symbolic or experimentally subjective intent.

Before the Depression few artists had fathomed this second more negative seam but among the exceptions were Charles Burchfield and Edward Hopper.

Charles Burchfield, Black Houses, 1936

Don’t these look like the eyes and mouths of human faces?

Racist blackface faces?

Regardless - I still don’t see a "somber inward tone" or "sterility and alienation"

Edward Hopper, Sunday, 1926

Definitely not joyous -

but especially negative either.

More like - contemplative.

Ben Shawn Unemployment, 1934

Anfam doesn’t mention the political art that preceded ABX and did not survive it.

Jackson Pollock, Camp with Oil Rigs, 1930-33

Like a battlefield.

Dramatic, depressing, violent, desperate.

Human life as a scourge to the planet.

Thomas Hart Benton, Boom Town, 1927-28

JMW Turner, Snow Storm - Hannibal Crossing the Alps, 1812

Ryder, Landscape, 1897-8

Pollock is on the book’s cover - and now he’s the first discussed regarding the origins of ABX. He clearly is key to this genre as Anfam defines it.

Whatever inspired Pollock - ask yourself which of the four places you would like to see more than once: Turner’s mountain snowstorm, Ryder’s verdant landscape, Benton’s industrial town, or Pollock’s campground.

Turner : spacious and magnificent

Ryder : mysterious and revelatory

Benton : busy though ominous - easy come, easy go

Pollock : sepulchral, claustrophobic, and depressing.

Benton and Pollock are among the pioneers of an American artworld that critiques rather than celebrates our lives - and their approach has been mainstream ever since.

Jackson Pollock, The Flame, 1934-38, 20 x 30"

Wow! One ugly fire - believably inspired by an Orozco mural - detail shown below:It does seem that Pollock ended up closer to Orozco than Benton.

So much destructive ferocity

Variations of its thrust pervaded his subsequent motifs (one painting from around 1947 was even entitled Vortex and already in The Flame (c. 1934-38) hints of some violently figurative subject contend against the sheer rhythms of brushwork. Indeed Benton had argued that the figure and design in general were reducible to angular schema but what is prophetic in The Flame is the lozenge pattern within its welter of strokes - similar to the oval vortex of Going West - that prevents complete disarray. The momentum of applying paint has therefore itself begun to convey both chaos and ordering. If an apprenticeship in Regionalism taught Pollock to deal with personal experience, within only a few years he had otherwise left its commonplaces behind.

Lozenge pattern in "The Flame" ? Certainly not one that’s repetitive - it’s too explosive for that. Not really a pattern at all, unless every painting is one. This memorable piece is about the energy that destroys.

Clyfford Still, Grain Elevators, 1928-29

A lively scene that, among other things, is a kind of history lesson:

the train arrives just as the coach is departing. Another interpretation noted the contrast of the sleek modern towers that recede into the distance with the junked out abandoned truck in the foreground. Has progress really been made here?

And the bi-furcated pictorial space is so disjointed - sweeping inward from the sides and confusing swirls up in the sky.

Anfam had this to say:

With its lateral elements correlated around a central massive focus, PH-855 ('Row of Grain Elevators') replies to Benton's precepts about pictorial balance expounded in an article of 1926. This seemingly academic search for a symmetry of sorts, where the bright red of a railway carriage at left counterbalances a green placed on the far side, would recur transformed in Still's most abstract works and so did the palette-knife technique. Here it is deft; twenty years on the results were to be surfaces scathed with violence. Nor could the sordid mechanical debris of the foreground have come from Benton or Wood with their buoyant folksiness, and his contemporaries from the 1930s recall the artist's moralizing eye even then. Before an expanse of sky the grain elevators rise above this disarray. Uprights that oppose their flattened surroundings occur in other compositions of this period and grew from a conviction that the space of the prairies had to be challenged by the 'vertical necessity of life'.

Clyfford Still, Houses at Nepelem, 1936

A compelling mystery though unpleasant and creepy.

I would not go through that narrow door in the green wall.

You just know it smells bad in that cramped space.

Here is Anfam’s discussion:

In the study of buildings at the Nespelem reservation done in the year after Still wrote a trenchant analysis of Cézanne the desolate note is stronger, akin in mood to Burchfield, whose empty houses are a haunted version of Regionalism, and to Pollock's treatment of a comparable abandoned factory at this time. Barren hills spread behind the architecture to repeat that symbolism of polarities - vertical against mass, presence in front of surroundings - which embodied Still's true subject from the first.

That might be said about any painting or sculpture whenever formal elements are what holds our attention way way more than subject matter.

Still, Two Figures, 1936

Not an especially happy naked couple.

No human faces - and the guy appears to have the head of a turtle.

Seems to say something like:

"I’m sick and tired of this miserable life"

Why should the viewer care —

unless misery loves company.

Around 1934 Still turned aside from moralized landscapes to concentrate upon the human figure. Compared to all the contemporary realisms the protagonists in these early paintings evoke the sheer plight of existence with an expressionist rawness. Distorted, journeying through darkened landscapes or isolated in space, they imply a mythos. By around 1936 he portrayed a male-female pair , a union in partition, interlocked within a dry grey field that brings the picture-within-a-picture of Picasso's allegorical La Vie (1903-04) to mind. Lithe yet bulging limbs - which had been Benton's stock signs for human vitality - now become labyrinthine contours while the despairing gestures and blind looks find their counterpart in the rasp of the palette knife's scrapings. Already, much of the future Still is here. It is in the unique and almost 'Nordic' vision which combines forcefulness and austerity, an attention to the picture's margin (the woman's hair is bright yellow) and the acerbic tones heightened, at the nipples, by crimson accents.

Picasso, La Vie, 1903

Here’s the Picasso referenced above.

Man protects woman; woman protects child.

More idealistic/romantic than the Still,

perhaps because the artist was only 22 years old.

As we all know, Picasso’s attitude would soon change.

(Still painted his nude couple when he was 32.

It feels mythic - drawing in the viewer to contemplate its mystery -

time and time again.

So too did Clyfford Still, whose origins compare with Pollock's.

Again, his family were of Scots-Irish provenance and moved soon after his birth on 30 November 1904 in Grandin, North Dakota, to Washington state and thence kept a homestead on the Alberta prairies. There his experiences proved decisive. The struggle to farm in a basically hostile environment swiftly worsened after a series of droughts began in 1917. Later the Depression turned an already collapsed economy into a wilderness again and even the landscape seemed to reiterate this hostility since the vast flat horizons reduced any human presence to a mere vertical accent. That the region aroused complex and even contradictory emotions in the artist was evidenced when he went back to it in 1946 and referred to a 'lostland'.

Although predominantly self-taught, Still at least registered at the Regionalist stress on the local habitat as a suitable starting point. These notwithstanding, PH-855 ('Row of Grain Elevators')

(1928-29) and the rather later (1936) scene of houses at an Indian reservation in the Washington mountains run at a tangent to Regionalism, a hallmark of early Abstract Expressionism which is clearest in its distance from the popular optimism and even utopian side of the New Deal era. Whether by Still, Pollock, Kline or de Kooning (who painted a brooding nocturnal Farmhouse in 1932), these are less tributes to nature outright than dark pastorals mindful of the human condition.

Franz Kline, Palmerston Pa, 1941

Franz Kline, Lehighton

Kline was pretty good at this kind of thing.

Anfam tells us he was fond of Old Masters at the Met,

so maybe he was thinking of El Greco’s portrait of Toledo.

just as he appears to echo El Greco's Fable.

Palmerton, Pa. (1941) portrayed his native locale from memory (like almost all the landscapes) as if no longer present to experience but still vivid in the mind. Together with other vistas, notably the fifteen-foot long mural of Lehighton (1946, commissioned by the local American Legion Post), these project what might be called a ramshackle panache which invokes the spirit of the place even as their locomotive power, literal and visual, runs aground on niggling detail and oddly foreclosed compositions. It is this unstable relation of part to whole that anticipates the zigzags lurching beyond the edges of Kline's later canvases while they still mesh internally into barriers or blockades.

An aesthetic response similar to mine:

"Lurching beyond the edges"

..as seen in both cityscape and abstract paintings.

Neither offer peace/comfort - just disruption/disquiet.

Franz Kline, Red Clown, (self portrait) 1947

Which kinda has me thinking of:

El Greco, Fable

Franz Kline represented the third Abstract Expressionist from a relatively rural background, the coal-mining region of eastern Pennsylvania around his birthplace of Wilkes-Barre.

To allocate each artist to town or country makes less sense than to observe how some wished their roots to be thought integral with their artistic make-up. So Pollock and Still emphasized their Western beginnings, Gorky his Armenian background and Smith an early contact with steel working.

Kline's renderings of Pennsylvania and New York obviously enough foretell the abstractions after 1950 in their blockish and dynamic structuring. They also possess idiosyncrasies standing in much the same relation to the future as the skewed Red Clown did to his own better-known exterior as the onetime high-school star athlete and All-American wit. Often there are pictorial obstacles, dark entrances or dishevelled arrangements which, like his introversion, were mostly but not entirely sloughed off in the otherwise imperious manner that eventually gained the upper hand.

As a youth studying art at Boston University (1931-35), in England (1937-38) and then resident in New York, Kline admired Rembrandt, Goya, Manet, Sargent and Whistler, all masters who had telescoped painterliness and drawing. These conventional sources, rather than the more sophisticated theories soon to develop in New York, convinced him that brushwork was indicative of a painter's energy. Here it is also noteworthy that he evinced considerable interest in the cartoon, a medium whose conventions for representing action are of course linear schema. Somewhat oppressive interiors and portraits from the early 1940s reveal that an academic training also taught Kline to compose in simplified masses

Franz Kline, Studio Interior, 1946

This is the first Kline interior I could find,_

and it’s quite small (3")

Yes - he is composing like a person familiar with old masters.

Though "ponderous" is not a word I would apply.

Was that big black splotch intended as

a frustrated reaction to a scene that was too ordinary?

Or- just an accidental finger print.

Kline: Studio Interior, 1947

Just found this one —- somewhat larger (7")

and much more exciting.

Study for Cardinal

Franz Kline, Cardinal, 1950

The wall size finished piece does look better than the study

Something is definitely on the move

as it rushes past the grid that contains it.

All action - not much reaction.

A metaphor for capitalism.

Franz Kline, Chief, 1950

The MOMA website tells us that Kline’s abstractions began after he projected the drawing of his rocking chair onto a wall.

Something more ominous here - like a big,ugly, black bug.

These paintings certainly do bring Chinese calligraphy to mind,

but without the sense of harmony/resolution.

This is art for the age of endless disruption

David Smith, untitled ( Virgin Island coral ), 1933

This is American abstract painting that’s far closer to what Arthur Dove was doing in 1910 than to the ABX of forty years later.

David Smith, Saw Head, 1933

Cute, clever, and just a little monstrous.

David Smith, Bombing Civilian Populations, 1939

Surreal figuration — not abstract.

Despite David Smith's ultimate pre-eminence as a sculptor, painting was his first pursuit and the great scope of his output came from straddling the two media. His investigations of different techniques and ways to redefine the three-dimensional object were invested with an imaginativeness that appears in essence pictorial rather than gravity-bound. To sculpture he

brought more than someone born straight into the discipline might have done and thus his work belongs to Abstract Expressionism from the start in its medley of realism and psychologically charged expression, which centred upon violence, energy or other disturbing themes from the 1930s onwards.

This is what ABX - as Anfam knows it - is all about - though it doesn’t apply to Smith very often - if at all.

Smith and the painters alike then progressed to more abstract languages that retained a meaningful impact. At their root lay a shared involvement with the human presence or its substitutes and the forces threatening its integrity.

Decatur, Indiana, where Smith was born in 1906 and then the Ohio of his formative years epitomized the small-town culture which (like Still, Pollock and Kline) he saw permanently altered by a growing technology. By 1925 Ford made a Model T every ten seconds and when Smith went to work that year as a welder and riveter for Studebaker it brought him into contact with what he would henceforth regard as the century's dominant force: the machine and its embodiment in the industrial materials of iron and steel. By itself this was nothing new, since the 1920s, from Le Corbusier to Precisionism, had been a romance with industrial utopias. Yet Smith jettisoned that straightforward optimism and identified mechanistic power as double-edged, a threat to humanity and an instrument of its deep-seated urges.

Two statements from the early 1950s summarized this symbolic understanding of his favoured materials: 'Possibly steel is so beautiful because of all the movement associated with it, its strength and functions ... Yet it is also brutal: the rapist, the murderer and death-dealing giants are also its offspring. And,

'The material called iron or steel I hold in high respect. What it can do in arriving at a form economically, no other material can do :.. What associations it possesses are those of this century: power, structure, movement, progress, suspension, destruction, brutality.

Having gone to New York in 1926, Smith studied at the Art Students' League under the Czech Jan Matulka who encouraged the distinct textural contrasts in his first curvilinear Cubist paintings which grew from collages into low reliefs and then free-standing objects. Smith observed, 'Gradually, the canvas became the base and the painting was a sculpture. After assimilating a pot-pourri of influences including the most recent European art movements (mainly via magazines) and African sculpture, Smith's education in modernism continued at firsthand during a trip to Europe in 1935 that took in Moscow, Paris

Some fascinating quotes here: iron "arrives at a form economically " - suggesting Smith was more a formalist than storyteller. And the quip about his canvas became the base of the sculpture that had been a painting.

Philip Guston, Painting, 1954

Febrile - rubbery

Order and chaos intermingling

No hope for resolution

but who cares?

Philip Guston, Nile, 1958

Seems to owe much to the wacky world of James Ensor.

Silly, surprising, over-charged, disturbed, intelligent in the ways of painting and organizing.

It floods the zone with things to cogitate and feel.

It's not about centering - it's about becoming flamboyantly uncentered.

A territory now worked by Molly Zuckerman-Hartung

Philip Guston, Conspirators, 1933

A political cartoon made for a Renaissance chapel -

connecting to current events rather than mythic liturgy,

it’s more like adolescent alienation than revelation.

Goofy enough for Chicago’s Hairy Who.

Too bad no color photos were made before it disappeared.

It’s where Guston returned when he abandoned abstract expression

with a righteous urgency for morality.

Yes - the piece is more about an artist being sly than an injustice needing..and Walker Evans's American Photographs (1938). Each deployed either silence, inaction or the isolated individual - elements shared with the early work of Guston, Siskind, de Kooning and Rothko, who echoed their introversion. Each also put an ostensible realism to unusual ends. One might go further still and remark upon a constant that almost defines the origins of Abstract Expressionism. It amounts to a puzzling quality of narrative suppressed or made secret. What we see is sufficiently occult to indicate a larger life outside the frame, of events and climaxes either just past or about to happen.

Pollock's Going West conveys this as surely as do de Kooning's transfixed sitters. So does the lighting that is crepuscular in Pollock, frozen in de Kooning and Rothko's subway series, or encapsulated in Still's Nespelem scene by what he said about Cézanne: 'the light suggests no particular time of day or night; it is not appropriated from morning or afternoon, sunlight or shadow. Rather than lay all these features at the doorstep of pittura metafisica, they are better considered as rudimentary signals of an involvement with time and its arrest.

His late 1920s watercolours of the Portland region are technically accomplished extensions of John Marin's crystalline idiom, but hardly anything more. Instead his ongoing need was to deal with the human drama. How else are we to explain an initial faux-naif painterliness that owes not a little to the art of the children whom he taught at the Brooklyn Center Academy and the unwilling, dreamy 'realism' - for quotation marks, as it were, are unavoidable - of the ensuing 1930s phase except as essays in picturing inward states of mind?

… or an involvement with a marketplace that rewards puzzlement and novelty.

Does it really disparage either these men or their paintings to suggest that they did what was needed to make a living ?

Mark Rothko, Subway Scene, 1938

Interesting (sepulchral?) feeling of a woman descending beneath the floor

while others appear to be floating above it.

Anyone who has travelled the New York system, however, will recognize the idiosyncrasy in Rothko's renditions. Claustrophobia is intimated by an imagery of descent and enclosure with columns that almost swallow the elongated figures and flatness becoming the real dramatis persona. Yet the subway's deafening noise is replaced by silence and Rothko probably remembered this when a decade later he mentioned a 'tableau vivant of human incommunicability'. Furthermore, an emphasis on surfaces implies that much remains beneath the surface, especially since an erstwhile public realm has been turned into an existential space. How this could accommodate the lessons of modernist art from beyond America's shores was the wider issue that others faced next.

Mark Rothko, 1928

Frenetic - nice relation between center and edges.

Not really satisfying though.

His late 1920s watercolours of the Portland region are technically accomplished extensions of John Marin's crystalline idiom, but hardly anything more. Instead his ongoing need was to deal with the human drama. How else are we to explain an initial faux-naif painterliness that owes not a little to the art of the children whom he taught at the Brooklyn Center Academy and the unwilling, dreamy 'realism' - for quotation marks, as it were, are unavoidable - of the ensuing 1930s phase except as essays in picturing inward states of mind?

Max Weber, Chinese Restaurant 1915

Continuous, unexpected patterned disruption.

Must have been in Chinatown.

Max Weber, November Twilight, 1942

Much more excited about the world outside than within.

Much stronger - and more satisfying

than any of Rothko’s scenes,

At face value Rothko's themes - women, urban scenes and interiors - sprang from the repertoire of his teacher, the pioneer modernist Max Weber, and accord with the quieter American Scene idiom of contemporaries like Isabel Bishop and the Soyer brothers.

Isabel Bishop

A nice feeling for traffic on an upscale urban street

It flickers between design and narrative, form and space.

Way less masculine than the Soyer brothers,

but that’s OK.

The street belongs to women as well as men.

More upbeat than a Rothko scene.

Mark Rothko, Interior, 1936

So puzzling.

Is the scene set in an upscale banquet hall?

What do the three woman have to do with the woman in the painting above them or the statues on either side?

Does it illustrate a novel?

Would certainly apply to these lines from the famous poem;

‘In the room the women come and go, Talking of Michelangelo’

Yet within the naturalistic framework the figures subtly conflict with their settings. Symmetrical doorways, for instance, frame two nudes, others are caught in the corners of rooms and though a street will plunge into depth human beings remain apart in the foreground. Interior (1936) is reduced to a facade enclosing a group of women who are themselves recessed into an indeterminate zone.

Sounds like the possible narratives puzzle Anfam as well —- though next he tells us that it’s "beside the point". anyway.

Paradoxically, the handling soon tends towards delicacy as if Rothko had learnt from his early involvement with watercolour to layer the application of paint in variously scumbled and scratched passages. To search for an exactly defined 'subject' is to miss the whole point since the early Rothko is consciously reticent just as his future art would be hard to summarize even as it prompted interpretation. Already flatness counters depth: facades after all announce what is behind them yet hide it. And. if Hopper surely prefigured these juxtapositions of sensuous figures and sparse architecture, Walker Evans's photographs prove anyway that the notion of life ceding to the inanimate was a leitmotif of the Depression.

The "exactly defined ‘subject’ "is a puzzlement in many paintings of the modern era. But not every piece has that indescribable visual quality that can compel curiosity. (I refer to a book that

elaborates 12 interpretations of Manet’s “Bar at the Folies Bergere". )

The series of portraits de Kooning did towards the end of the 1930s (besides his far more abstract compositions) cast a similar doubt over what they seek to portray. He had left

Holland in 1926 and the legacy of a training in draughtsmanship at the Rotterdam Academy of Fine Arts survives in their precisely delineated faces and anatomy only to yield in turn to numb expanses bereft of finish or focus. To earn a living de Kooning painted features on mannequins during these years and his figures always retained a resemblance to the wide-eyed stare of dolls.

DeKooning, Man, 1939. (age 35)

A nice comparison with another Dutch artist:

Rembrandt, 1626-36. (age 20-30)

Neither were portraits of a client -

both men appear to be quite awake, in-the-moment,

though one is obviously dressed up as a costume model,

while the other is more like a slice of ordinary life.

And the one was made to be tasty, decorative, and comfortable

while the other has the grating anxiety of a real moment in modern life ( or life whenever, wherever)

Though it’s not as intense and confrontational as Kokoschka;

Kokoschka, Portrait of Adolph Loos, 1909

Man (c. 1939) [35] shares in a predicament that came to the fore during the Depression and was exemplified in novels such as Faulkner's Light In August (1932) and Richard Wright's Native Son (1940) whose main characters lack identity, cornered between definition and a void.

That’s one way to put it - though we’re compelled to pay attention to that native son, Bigger Thomas - because he kills people.

DeKooning’s poor fellow would only be of interest to a family member or a case worker.

If ever he even existed.

Walker Evan’s, Subway photos, 1941

An anxious lad - concerned about missing his stop?

Also close to de Kooning's idiom (apart from its references to Mannerist portraits, Ingres and Gorky) are Walker Evans's New York subway photographs of 1938-41 [36] (and again Burckhardt did similar studies) which portray urban inertia through the gaze of those caught unawares, at once passive and unquiet.

Rudy Burckhardt, 1946

Similar to the Isabel Bishop painting shown above.

The thrill of order in urban happenchance..

(and why is that fellow in the distance standing still in the middle of the street?)

When Rothko himself depicted the subway after 1936 the results were meta-landscapes of the city's nether regions, not wholly new as Reginald Marsh and Joseph Solman (with Rothko a member of the splinter group called The Ten) had already treated it, preceded by Orozco in a sharply constructed series of 1928-29 and Hart Crane who included an infernal underground sequence in his epic poem The Bridge

(1930).

Joseph Solman, 1967

Local color. Cheerful but——

I do prefer Rothko’s weirdness.

(Note: it was painted on a racing form from the racetrack where the artist worked part-time. Not having joined the trend in abstract expression, he needed the extra income )

*******

This final sentence serves as something like a conclusion to the chapter. The discussion of surfaces only applies to Rothko - but the transition from public space to existential applies to them all. Except perhaps for David Smith. While his contemporary , Giacometti, is notably an existential sculptor — Smith is as exuberantly self expressive as a precocious child.

So far, Anfam has ignored commercial motivation in mid 20th C. American painting — which is like ignoring religious motives in the art of 17th Century Europe. I would really like to know when each of these artists first hit the big time. Isn’t that essential to a history of this genre?. I’m not sure that abandoning figurative expression really improved any of their work - except for David Smith - whose only connection to the others, as I see it, was social.

But I do appreciate how Anfam discusses specific examples to tell his story — and that discussion seems sensible and informative. Sharing many quotes from the artists, apparently he wants to see the artists as they saw themselves.

No comments:

Post a Comment