Chapter 4 of Paul Crowther’s "The Phenomenology of Modern Art" (2012)

Note: Mr. Crowther writes philosophy- not art history or criticism.

He introduces specific works of art only as they relate to his ideas.

His discussion of those examples, however, is his only text that interests me.

So I jump from painting to painting

giving my own response to the piece before studying his.

*********

Crowther wrote:

looking at the influences on Cezanne, or his technique, or even his own pronouncements about painting. Merleau-Ponty offers, rather, a phenomenology, that contextualizes all these factors in relation to the question of perception. This approach addresses, in the first instance, the character of Cezanne's immediate artistic precedents, and then, in more sustained terms, his own work.

In this respect, we are told that:

Impressionism was trying to capture, in the painting the very way in which objects strike our eyes and attack our senses.

Objects were depicted as they appear to instantaneous perception, without fixed contours bound together by light and air. ... The colour of objects could not be represented simply by putting on the canvas their local tone, that is, the colour they take on isolated from their surroundings; one also had to pay attention to the phenomena of contrast which modify local colours in nature.—Merleau-Ponty

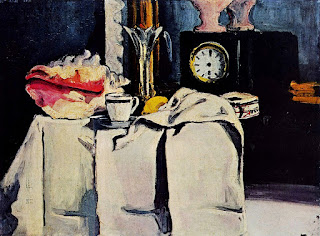

Cezanne, The Black Clock, 1870,, 21 x 29"

(The above painting is discussed in this chapter.

I have selected all the other still-life’s that are shown below)

I badly want to perceive reality (of which, for me, paintings are a significant part) — but I have no interest in the perception of reality as an academic study. We do whatever we can to figure things out - making adjustments as we go. But Merleau-Ponty has prioritized "perception of reality" in some really great paintings whose own painterly reality offers so much more for those who can feel it. Sure - they present recognizable people, places, and things — and that’s part of the discussion about them. But that’s not the reason we’re talking about these particular masterpieces instead of random selections from a local art fair. And however much these painters aim to record "what strikes the eye", their own brush strokes can’t help but express their ideals, taste, experience, spirit, discipline, and personality, as well as their moment in history.

There’s a humor in the above painting that is rare in Cezanne - and it seems to update the below famous work that was Chardin’s reception piece into the French Academy.

Chardin, The Skate, 1727

Cezanne’s piece charges across its flat surface. Chardin‘s is static - it’s going nowhere but in - as he develops more depth - with a complexity that seems to be for its own sake. This is a show-off demonstration piece - and it has its own wry humor as well — the seeming smile on the face of the poor, dead fish staring down at the lively cat.

And time is in issue in both. Cezanne paints in a clock without hands. Chardin paints a kitten leaping —- frozen in time , it never will land.

Manet, The Salmon. 1868

Here’s a piece contemporary with Chardin — also moving horizontally across its surface - though using a protruding knife to still suggest some pictorial depth as a counter-motion to propel the fish into the lemons. Cezanne does feel more coarse and rustic.

Monet, Still Life with pars and apples, 1867

The tenderness of this fruit’s skin seems to be the subject here. Appetite is an issue. Pictorial space is not — it’s just there to accommodate the delectables,

Courbet, Still life with apples, pears, and pomegranates, 1871

Another contemporary still life,

this one pays more attention to the erupting fullness of each fruit.

As with Chardin, we’re in a dim, profound space,

like a chapel in a church,

to contemplate these works of nature.

Cezanne, Apples and Pears, 1891-2

And here’s what Cezanne was doing 20 years later. The laws of natural perspective are scoffed. It’s a carefully choreographed dance of form and color on a surface. Wonderfully balanced - it’s much more about working a painting than fruit on a table or any other narrative.

*****

… and now we return to Crowther/Ponty’s discussion of "The Black Clock"

Such a procedure results in works that do not involve some point-by-point correspondence with nature. They effect rather a generally true impression that arises from the relation between the action of the different parts of the visual manifold upon one another. Such a process, however, in emphasizing atmosphere and breaking up tones, appears to submerge and desub-stantialize the object. The importance of Cezanne is that, in works after 1870 he tries to find the object again behind the atmosphere (a point that, as we saw in Chapter One, is raised by Deleuze, also). This involves paintings that do not break up tonal values, but replaces them, rather, with graduated colours, expressed in chromatic nuances distributed progressively across the object. In this respect, we might consider a major transitional work, namely The Black Clock of 1870

Here, the drapery is treated in a way that does not obsess over the light effects that play across its surfaces, nor does it delineate the textural richness of the material. Rather, the white colour declares the folds in more insistently plastic terms - emphasizing, indeed, the way in which they are defined by the substantial presence of the table beneath them.

And again, the clock itself, is not presented in terms of reflecting light or of the details of its material, but with a closely modulated. and - one might almost say - massive blackness that makes the physicality of the object insistently palpable in direct visual terms. It is because of features such as this that Merleau-Ponty suggests, rightly, that in Cezanne's mature work there is a colour strategy that stays close to the object's form and to the effect of light upon it.

However, it involves, also, considerable licence - in some cases the abandonment of exact contours and the assigning of priority to colour over outline. The effect of all this is very different from impressionism. In Merleau-Ponty's words,

The object is no longer covered by reflections and lost in relationships to the atmosphere and other objects: it seems subtly illuminated from within, light emanates from it, and result is an impression of solidity and material substance.

In this way, Cezanne brings about a return to the object, that does not give up the importance of the impressionist aesthetic

of nature as model.

Though I do find some Impressionist paintings that appear to de-substantiate an object with reflections, atmosphere etc (especially by Renoir) --none precede 1870. "The Black Clock" does not conflict with its predecessors. Crowther and Ponty are off on their chronology.

The question arises, then, as to the stylistic means whereby Cezanne achieves all this. Interestingly, Merleau-Ponty identifies factors that distinguish Cezanne's work from more geometric, perspectivally orientated ones.

Cezanne, Portrait of Jeffroy, 1896

He mentions several works in relation to this, including the celebrated Portrait of Geffroy. In this work, the table on which the critic is working appears almost upended and tilted towards the viewer, and the books placed upon it, seem to be anarchic elements that de-stabilize the unity of the pictorial space which they articulate.

However, this impression only arises if one considers these features individually. But the point is, of course, that this analytic identification of specific pictorial components is secondary to our perception of the work in overall global terms. Then such

"inconsistencies' take on an entirely different significance. As Merleau-Ponty puts it, 'perspectival distortions are no longer visible in their own right but rather contribute, as they do in natural vision, to the impression of an emerging order, an object in the act of appearing, organizing itself before our eyes.'

Isn’t that how all successful paintings feel? It’s in the act of organizing itself before our very eyes. This painting has an interesting history. Cezanne expressed frustration with it and left town, declaring it unfinished. Presumably that’s because of the splotchiness of the face. Looks pretty good to me - but I can see how portraits might frustrate a painter like him. A mark that fixes a facial feature might damage the painting - and vice versa. He was more concerned with painting as an expression of his own plastic imagination than as the portrait of whoever. And this man, a favorable art critic, was important. He was not just the gardener.

The radical innovations of Cezanne extend much further than factors bound up with the disposition of items in pictorial space. For, at the very heart of Cezanne's achievement, according to Merleau-Ponty, is a specific relation between brushwork and colour. He describes what is at issue, here, as follows:

If one outlines the shape of an apple with a continuous line, one makes an object of the shape, whereas the contour is rather the ideal limit toward which the sides of the object recede in depth. Not to indicate any shape would be to deprive objects of their identity. To trace just a single outline sacrifices depth - that is, the dimension in which the thing is presented not as spread out before us but as an inexhaustible reality full of

reserves.

Cézanne's painting, however, is true to depth. It follows the voluminosity of the object through modulated colours and by indicating several outlines to it. This flexible stylistic means captures the object's shape in the same terms as it emerges in perception itself. Indeed, Merleau-Ponty continues,

The outline should therefore be a result of the colours if the world is to be given its true density. For the world is a mass without gaps, a system of colours across which the receding perspective, the outlines, angles, and curves are inscribed like lines of force; the spatial structure vibrates as it is formed.!°

In these remarks, Merleau-Ponty is suggesting that Cezanne presents outline, in effect, as a dehiscence emerging from the inexhaustible pulp of the object's colour and light - just as, in perception itself, the things qua discrete entities emerge from Flesh. Cezanne returns us to the primordial conditions of perception.

Given these points, it is clear that already, in 1945, Merleau-Ponty's thinking about Cezanne is pointing to the notion of Flesh which is such a distinctive feature of his later thought.

This is one of those rare occurrences when the example of a specific art practice is taken as pointing towards a more general philosophy of perception and Being.

Indeed, there is a further remarkable feature involved. In recent years, it has become fashionable to affirm the importance of Being, and humanity's relation to it, in 'ecocentric’ terms, that is, ones which emphasize that the human world is only one aspect of a much broader notion of Being that encompasses the full diversity of organic and environmental factors.

"Dehiscence"? Love that word! But it would be more correct to say that outline is a dehiscence of the "inexhaustible pulp" of an artist’s spatial imagination. Lines and patches create volumes only as an artist pulls them into the illusion being projected/imagined onto the paper or canvas. Without that uncommon ability, they can only be marks on a surface.

Crowther and Ponty's philosophical speculations are not connected to their own experience with pencil or brush.

We live in the midst of man-made objects, among tools, in houses, streets, cities, and most of the time we see them only through the human actions which put them to use. We become used to thinking that all this exists necessarily and unshakably. Cezanne's painting suspends these habits of thought and reveals the base of inhuman nature upon which man has installed himself.

The point is, then, that Cezanne's style discloses Being in a non-anthropocentric way. Conditions of human perception are traced as emergent from a more encompassing sense of Being rather than as expressions of a notion of Being that has been appropriated on the basis of instrumental thinking and social attitudes.

Rembrandt, 1650 (Met)

Is this view anthropocentric - or "more encompassing" ?

Could it be both? Man in Nature - and - Nature in Man.

Not one without the other.

The homes are like bird nests.

Achille-Aetna Michellon (1796-1822)

Like the Rembrandt shown above, this mostly seems mostly to be image-centric.

Same thing with the early work of his pupil, Corot.

Constable, Salisbury Cathedral, 1825

As a counter example - this piece would have to be called anthropocentric.

(If not deo-centric)

God is is at the center of this universe.

It was commissioned by the bishop of the cathedral

which it presents as if a portrait. Nature is just there to provide a frame

and there’s even a gentleman on left who points towards it

to make sure you don’t miss its remarkable spire.

Doesn’t make it any less of a painting.

Of course, as we saw earlier, for Merleau-Ponty, all painting has ontological significance through its disclosure of total visibility', that is, its presentation of a visible item or state of affairs, together with the colour, light, and other relations which are the basis of its presentness to vision.

However, Cezanne's work is more than just this. For, in its specific mode of resistance to a mere illusionism based on classical perspective, his painting emphasizes the emergent character of perception itself. Not only is the relation between the visible and invisible disclosed, but is so in terms of that flesh and voluminosity of depth from which the human reality is itself emergent.

Cezanne, Gardanne, 1885

One might consider this in relation to a work such as Gardanne of 1885-6 (Barnes Foundation). Here, the individual forms and spatial units comprise both natural features and buildings. However, in the way that Cezanne treats these, there is no hierarchy of visual significance. By declaring the more basic geometric features of the building, they are given a kind of matter-of-fact visual substantiality that is true to their character as edifices, but which presents them visually only as palpable articulations of spatiality, rather than as buildings that serve such and such a function. There is an equalization of nature and human artifice that Cezanne achieves through making the contents of pictorial space at once unstable, yet, paradoxically enough, emphatically substantial.

Yes - in the sense that every plane (in tree or wall) seems to exist only as it contributes to the dynamism of the whole painting - as the right tectonically pushes against the left and the town rises upward as a result.

No - in the sense that this painting celebrates a human structure - the tower above the town.

In his later work, Merleau-Ponty extends this interpretation of Cezanne to the painter's final phase - with its relatively free-floating planes of colour, and strategically unfinished white areas of canvas/paper. In 'Eye and Mind' we are told, for example, that,

there is clearly no one master key of the visible, and color alone is no closer to being such a key than space is. The return to color has the virtue of getting somewhat nearer to the heart of things, but this heart is beyond the color envelope just as it is beyond the space envelope. The Portrait of Vallier (from Cezanne's last few years of life sets white spaces between the colours which take on the function of giving shape to and setting off, a being more general than yellow-being, or green-being, or blue-being."

Cezanne, portrait of Vallier, 1906, 25" x 21"

Cezanne had much less problem with this portrait because, after all, it was only the gardener. The sitter’s character was not an issue - only the painting as a painting. Letting the white surface show through is much more common in watercolor - but it works just as well in oils - providing luminosity and really perking up a pose that is, let’s face it, rather boring. Ponty’s talk of white-being versus blue, green, or yellow being is much more about philosophy than painting.

The features described here by Merleau-Ponty as relevant, especially , to the extraordinary series of paintings of Mont Sainte Victoire that Cezanne did between 1900 and 1906. Consider, for example, a treatment of this subiect done between 1903 and 1904

Cezanne , Mt. St. Victoire, 1902-4, 29 " x 36"

Several views of this mountain came to the Cezanne show in Chicago two years ago. They are not among my favorites - I don’t enjoy being in them . Cezanne is the great explorer. He tries things out — and sometimes the results may feel awkward. (Example: his male nudes). He must have liked this monumentality more than I. But they do have a certain nervous energy, excitement, joy of living not felt in photographs - example below:

Cezanne's painting, here transforms the carefully modulated colour passages of his earlier works into broader spatial masses and relations that are expressed through mini planes or facets of colour. These have the effect of further equalizing out the relation of the built landscape and its natural setting.

Indeed, this equalization is so emphatic that it begins to appear that both human and natural landscape are modulations of a more fundamental Being as spatializing - whose generative pover is evoked by the brooding agitation in terms of which the coloured planes and flecks of white articulate the painting's surface. In effect, the ontological ecocentrism of Cezanne's first mature period takes on a more metaphysical turn.

I’d go for "being as spatializing" (would also apply to J.M.W.Turner) …. except that, in person, the painting made me feel like I was outdoors staring up a mountain as the sun beat down from overhead. It felt like I was there - in a real place, not a fantasy or theoretical construct.

There is an immediate question that must be asked. Merleau-Ponty emphasizes the ontological-metaphysical significance of Cezanne's style, as a distinctive feature. But why should this be regarded as positive? Why should we want painting to provide the kind of insights that are achieved more articulately through philosophical explanation? Indeed, might it not be said, reasonably, that Merleau-Ponty's interpretation, in effect, reduces Cezanne's work to a mere bearer of theory?

A related worry arises. The philosophical significance that Merleau-Ponty assigns to Cezanne has not been affirmed by the artist's other major interpreters. In fact, it is only when viewed in relation to Merleau-Ponty's own work, that Cezanne's work takes on the ontological significance that he assigns to it. But suppose Merleau-Ponty had never been born, and had, thence, never formulated his philosophy. How would Cezanne's work express this arcane philosophy under those circumstances?

Crowther spends several pages on this line of reasoning - and I’m really only interested in the intersection of philosophy and specific paintings. So I’ll skip this discussion. I have no problem with Ponty’s ideas as they express his personal experience with Cezanne.

Cezanne, Bibemus Quarry, 1895, 25 x 31

Wish this piece had traveled to Chicago! Such a salute to planet earth - as well as a powerful personal expression in paint.

Now in literary works and moving images, the same capacity is manifest, but tends, phenomenologically to be submerged in our following of the narrative flow. Painting, however, makes the capacity manifest. For it presents and celebrates itself immediately as a virtual alternative to the place and time we presently occupy, and as one that, qua virtual, is not subject to the vicissitudes of finitude and mutability. Indeed, the very fact that the painting has edges - often declared by a frame - declares, insistently, that it presents an order of Being separate from that

of ordinary reality, even while operating at the same level that mainly defines that reality, namely the visible. What Merleau-Ponts fails to negotiate in other words, is the way in which painting as an idiom of pictorial representation not only evokes the conditions of visual perception, but intervenes upon them through planar idealization..

Let us now consider this in relation to Cezanne. In this respect, a fine work to look at is the Bibemus Quarry of 1898-1900 What is striking is the way in which Cezanne visually constrains oblique dispositions among the different rock formations , and makes them appear synchronous with the picture plane. At the same time, however, this alignment evokes a visual tension - as though the formations are striving to re-assert their oblique projection. This makes them seem dynamic - as though their form is emergent through correlation with basic bodily movements, rather than with the demands of human instrumental interests in the organization of the landscape (and this, even though the landscape feature in question, a quarry, has been created by human artifice).

Words cannot really account for how the totality of a visual design is working — but Crowther did surprisingly well in his above discussion of constrained obliques and visual tension. There is also a tension between crushing inward and expanding outward.

Meg Lagodzki, 10 x 8, Quarry Painting

Here’s a contemporary painting of similar subject matter. It does create pictorial space - with foreground-middle ground- and background. But it also thwarts it - though not as thoroughly as Cezanne did. It’s really a nice piece - I feel the uncomfortable heat of a sunny summer day and the eternal chaos of the randomly disposed rocks (in contrast with the more settled distant tree line.

It’s currently for sale at about 1/1000 of what a Cezannne now costs. A real deal.

Now, of course, this is precisely the kind of feature that Merleau-Ponty takes to be evocative of (what I have called) the ecocentric relation of humanity to the world. However, this effect is very much a secondary feature. It is dependent upon precisely the kind of planar idealization that I have described in the foregoing.

The various rock formations are visually discordant with one another. The three-dimensional emphasis of their more oblique projections (which would be dominant in any direct perception of the quarry) have, as it were, been tamed, and redistributed in harmony with the picture plane.

This places the dynamic, emergent character of the painting's content in a very different light from the one emphasized by Merleau-Pontv. There was a Bibemus Quarry, but whereas, as we have seen, a photograph declares its status as a visual extract from the spatio-temporal continuum, in a picture, the before and after of the represented scene is entirely open.

In the present case we cannot tell that Cezanne's painting represents an actual physical site purely on the basis of the painting.

I have always felt an intense reality in Cezanne landscapes ~ as if I were seeing the same hills and sky as the painter, and I can feel the sun on my skin.

But still, as Crowther states below, I nevertheless feel that time is standing still — I am in an eternal moment. Actually, many paintings make me feel that way. My mind is locked on the oneness of the visual phenomena - there is no opportunity to speculate on any before or after. If a painting doesn’t do that for me, I’ll call it an illustration.

Because of this, our perception of the work has an openness in temporal terms. Its emergent appearance does not locate it put it in some strict linear succession of spatial contents in time, but as an act of showing. The only linear temporal succession moled in reading the scene is our sense that it was physically panted by an artist placing marks on a surface, and that when it was complete, the artist became occupied with something else.

Temporal linearity, in other words pertains to the act of making rather than being internal to the virtual space represented in the painting.

N.C. Wyeth, One more step Mr. hands and I’ll blow your brains out

Awkward and stodgy as a painting - wonderful as an illustration

making me desperate to know how it will turn out.

Below is how Crowther concludes:

.

The upshot of this is that the planar structure is no longer swallowed up in the presentation of depth, but presents itself as the bearer - even the creator - of pictorial depth. Paint's intrinsic creative power is affirmed in visually immediate terms.

Cezanne inherits this but also pulls off a remarkable reconfiguration of the planar emphasis. As we have seen, from the 1870s onwards he develops a brushstroke technique that has the paradoxical ability to both affirm the three-dimensional substance of objects and natural formations while at the same time emphasizing the virtual two-dimensionality of the picture plane.

This creates the total visibility effects that Merleau-Ponty sees as the basis of Cezanne's importance. I have argued, howevel, that what is more fundamental is the aesthetic relation between affirming the plane and plastic qualities which give rise to these effects. For it allows the gap between painting's own nature and pictorial formats, and the visible palpability of the subject matter, to be diminished.

No one can deny Cezanne’s influence on so many who came after - including the early Modernists and the entire Soviet school.

In my art-centric world, however, Cezanne is primarily important because of the uniquely powerful spirit of some of his paintings.

Here are a few contemporary local (Chicago) examples that, intentionally or not, echo him;

Sandra Beaty, Caldwell Lily Pond, 2024

Dmitri Samarov (b. 1970) View of the hills outside Fiesole

No comments:

Post a Comment