(this is chapter 16 of John White's "Birth and Rebirth of Pictorial Space".

Quoted text is in YELLOW.

Text quoted from other authors is in GREEN)

Quoted text is in YELLOW.

Text quoted from other authors is in GREEN)

Old Kingdom

New Kingdom

VASE PAINTING IN GREECE AND ITALY

The painters of ancient Greece hold an unique position in the history of spatial realism. It was in their work that the absolute dominion of the flat, pictorial surface was, for the first time, seriously challenged. This knowledge only serves to throw into relief the obstacles with which the lapse of time has fortified the approaches to their art.

The Egyptian New Kingdom painting shown above seems to be dealing more with pictorial space than the Old Kingdom relief shown above it.

Doesn't the left arm of the cute, naked servant seem to be holding a bowl that is poised in the middle of an empty volume between the figures? As if the girl's breast is further back, deeper than the surface of the painting?

And hasn't the left arm of the flautist been foreshortened, with the folds of drapery stepping back from the hand to the shoulder?

(both of these New Kingdom paintings are from the tomb of Nebamun, C. 1500 BC)

But one thing that I've yet to find is a straight line that goes back into space.

Drawings done of the Amphiaraos Krater

(disappeared from Berlin Museum in 1945)

Proto-Corinthian Chigi Jug

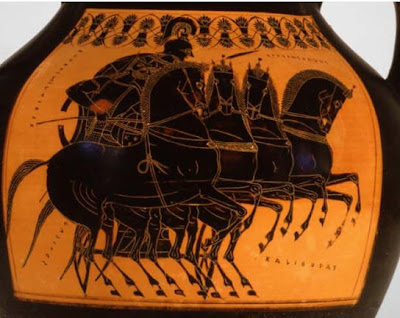

A certain sense of space is imparted to the figure decoration of Greek vases at a very early date by the complex overlapping of form on form. The Proto Corinthian Chigi Jug provides perhaps the best-known illustration of how much could be achieved by the simple superimposition of completely planar forms, and a similar prefiguration can be seen in the Corinthian Amphiaraos Krater in Berlin. In the latter there is once again no figure diminution, and no decorative piling upwards over the pictorial surface. The hustling crowd races along the narrow picture band, once more upon a single ground line. On the extreme right a sense of crowded space and movement is gained by overlapping horse on horse twelve deep, by chariots glimpsed beneath their arching bellies, and by means of streaming reins and half-seen charioteers. All this is crystallized by the sudden juxtaposition of the wheels of two pairs of quadriga. Here, as elsewhere in the scene, the depth created visually is small compared with that implied by the number of horses, chariots, and drivers. The two wheels of a chariot in profile coalesce into a single round. The four wheels of each pair of chariots produce the mock-foreshortening of a single galloping quadriga. The vitality of the design imparts a sense of space that overrides the logic of its factual limitations.

The problem with discussing pictorial space in ancient Greece is that all that remains are painted pots, and even then, there are issues with dating and, of course, the fact that the painted surfaces are curved, so that from any single POV, the lines to the right and left will be receding backward into the real space inhabited by the pot.

A "certain sense of space" can be found, but is it any deeper than the New Kingdom paintings from a thousand years earlier?

550-530 BC

(Toledo Museum)

A blending of the two original patterns (front and side views) is achieved in which the front view of a chariot is combined with charioteers and horses in pure profile These are sometimes set more or less directly in front of the actual body of the chariot, which may be almost entirely hidden. Often, as in the example illustrated, the main intermixture of forms is accompanied by an extension of the principle to the smaller elements of the design. In the original front-view quadriga pattern all the horses’ heads were shown in sideview. Now, in the second horse from the right, the body is shown moving one way in pure profile, whilst the neck is twisted in the opposite direction, once again in profile, and the head itself is in a purely frontal setting.

By these means the artist can almost create an impression of diagonal movement in the design as a whole without introducing a single foreshortening. Just as the rapid succession of the photographic frames produces movement on the cinema screen, so here the rapid shuttling of the planar forms almost induces a diagonal compromise within the mind of the spectator. The result is what has often been called ‘pseudo_foreshortening’, and if this type of composition were the only evidence at hand, it would be very difficult to say how much the impression of depth and diagonal movement is merely a contribution of the modern eye, or to what extent it represents a tentative indication of the artist’s own intentions.

In the above examples, White compares pseudo-foreshortening (above) with foreshortened frontal (below)

We can note how much shorter the torso of the horse is in the second painting compared with the first.

And we can also note how the circular wheels have become elliptical in their foreshortened view.

Eos Chariot, 430-420 BC

State Museum, Munich

White does not mention the above example,

but it's parallel pair of chariot wheels

seen from a central POV

are foreshortened just as the opposite walls

of a rectangular room would be.

East frieze of the Delphic treasury at Siphnos

White chose this piece to exemplify fore-shortening in sculpture because in his time it there were remnants of a paint job that depicted elliptical wheels on the chariot.

As you can see above from a recent photograph, that paint has been cleaned off (was it identified as a much later addition ?)

But many examples of foreshortened figures in three-quarter view can be found among the sculpture from the Parthenon:

From the time of Exekias onwards the painters of the vases tackled the foreshortening of three things, namely sails, and shields, and chariots, with a boldness which is quite unequalled elsewhere in their work. The diversity, and the particular nature of the objects singled out, appear to indicate that the reasons for their selection lie within themselves, and not in some unknown, external factors.

The sails that billow over Exekias’ vine-bowered ship and over the more prosaic vessels of Nikosthenes and his contemporaries, hang beneath a curving yard which lies in one plane with the hull, instead of at right-angles to it. It is in the same non-functional relation to the ship itself as is the standard, full-face torso to the profile legs beneath it. The impression of foreshortening is created by the curves which flow from the attachment of the halyards to the stern half of the ship, and its vividness is accentuated by the brilliant device of the wind-scalloped new moon of canvas, seen from the other side, which the artist adds upon the left. The painter’s aim is achieved by means of easily drawn, and decorative curvatures that do nothing to disturb the unbroken surface of the cup.

The contrasting upper and lower parts of the design on this cup create a delightful, dreamy sense of space that White does even begin to discuss.

And it has nothing to do with foreshortening.

The nature of these curves appears to be the main connecting link between the sails and the foreshortened shields which form the second favoured group of objects. Here, the curves required to change the side-view of a shield into a sharp three-quarter view are visible already in the convex forward contours. The very simplicity of the task of conversion may well have proved a major contribution to its popularity.

A red-figure composition executed by Euthymides in the final years of the sixth century seems to indicate that the leading artists were acutely conscious of the nature of the innovations they were making. The design, which shows three naked dancing figures, is remarkable for the quality of the anatomical drawing, and particularly for the astonishing mastery with which the artist handles the extremely difficult foreshortening of the central figure’s sharply twisting back. There can be little doubt as to Euthymides’ meaning when he added the self-satisfied inscription—’Euthymides son of Polios drew this as Euphronios never did.’

I'd say that Euthymides should have been justly proud of the beauty and liveliness of his design -- of which the "extremely difficult foreshortening" of the back was just one, small part.

The Washing Painter, Nuptial Lebes, the Met.

Dionysiac Cult, Louvre

Eretria Painter

White then chronicles the emergence of 3/4 views of tables and chairs in the 5th C. BCE, using the above examples, culminating in the "direct centralized recession" of the Eretria painter.

(BTW - the piece shown above from the Louvre is nearly identical to the piece from the British museum which White shows in his reproductions.)

Perhaps its only coincidental, but that piece by the Eretria painter feels like figures set into a picture box, rather than the pieces shown earlier, where the figures aggressively make their own space.

A useful starting point for any study of the further expansion of ideas of space and three-dimensional solidity that is revealed by South Italian vases, is the well-known volute krater from Apulia, decorated with the story of ‘Orestes and Iphigeneia in Tauris’.

One of the many striking things about this vase is the solidity of the altar upon which Orestes sits. This new boldness in the handling of the foreshortened frontal setting is a characteristic feature of the best Italian vases. Equally characteristic is the fact that an increased ability to give a convincing appearance of three-dimensionality to relatively complex forms is not accompanied by the evolution of a vanishing point or even of a vanishing axis.’ There is a tendency for the orthogonals to converge, but quite haphazardly, and they occasionally stay parallel to each other, or, in several cases, actually diverge to some extent. These divergences are not so strong, however, as to cause a serious disruption of the general pattern. In plain, rectangular boxes, simple stone blocks, marble bases, stelae, and the like, all the few, visible, receding lines quite frequently converge. But this is rather a reflection of the lack of complexity in the object which is represented, than a witness to the attainment of a higher degree of organization than is shown in the altar on the Orestes krater.

The altar, with its white front and its red, receding sides, which serve to emphasize its clarity of volume, draws attention to a further spatial innovation. Whereas in the Attic vases a low viewpoint is the unvarying rule, except occasionally in the curving backs of chairs, here the upwards flowing lines establish a high point of view. This signifies a change of attitude towards the base or groundline, and foreshadows the consolidation of a visible, horizontal ground plane, with its untold consequences for the subsequent history of the visual arts.

The ground plane had already been suggested at a very much earlier date in Assyrian, and in Minoan art, but had not congealed into a stable, horizontal platform, and no strong tradition was established to be handed down to subsequent civilizations. It had been the surface-climbing hill-scene that had achieved the greater popularity in the early history of the Middle East, although with hardly less impermanent results. This hill, or rock convention does not reappear in Attic art until the mid-fifth century, when it can be seen, upon the vases decorated by the Niobid painter, as a probable reflection of the fresco paintings of the two great innovators, Polygnotos and Mikon. It is this convention which is used once more in the Orestes scene. Here it places in sharp focus the essential contrast that exists between its unformed, vertical hill-surfaces with their implied, but hidden figure platforms, and the level ground which is created by the bold recession of the left side of the altar. The element of conflict is quite clear, although this level space is still, as yet, almost unable to extend beyond the altar’s marble boundaries even with the help of the two figures standing on its right.

The high viewpoint and the confident foreshortened frontal setting of the altar are still more revealing when they are considered in conjunction with the temple that appears above the latter on the right-hand side. This seems to be softly, but undoubtedly oblique in disposition, although the recession of the pedimented forward face is so slight that the first impression may quite easily be that of a foreshortened frontal building. In any case, there is a complete change of viewpoint when the temple is considered in relation to the altar. This is yet another illustration of the familiar observation that neither the Greek, nor the Italian vase painters ever felt that it was necessary to coordinate the viewpoints of a number of separate objects. This is true, however, only in the horizontal sense. The casual collection of things seen indiscriminately from left or right, or straight ahead, is not accompanied by an equally carefree attitude to things seen from above or from below. This again is illustrated by the painting of ‘Orestes and Iphigeneia’. Here there is no question of a single eye level, as there are neither vanishing points or vanishing axes to establish such a line. On the other hand there is no vertical conflict comparable to that occurring in the horizontal sense. The altar at the bottom of the picture is seen quite sharply from above, whilst the temple at the very top of the scene, with only its upper half in sight, reveals down-sloping lines as if it were viewed from a slightly lower level.

Is this still the earliest known example of a fore-shortened rectangular solid?

Indeed, there's two of them, and even if the altar and temple may have a different POV, the hilly horizon line makes it possible for them to be seen from the same level.

White is telling the story of "spatial design in antiquity" as if it were a gradual, evolutionary development. But fore-shortened rectangular solids are part of everyday visual experience for people who live in box-like buildings - so it's just a matter of drawing from that experience whenever it might apply to some narrative purpose.

The story on this pot seems to begin with "Once upon a time..", while the earlier stories began with "Here is ...."

Orpheus in Hades, 4th C. BCE

White notes that the above exemplifies a coordinated POV for the furniture and building that contains it.

The fact that this development of space on the curved surface of the vase should be so closely similar in its essentials to the patterns which were later to evolve on the flat planes of panel, wall, or page, shows that the tension of the smooth, continuous surface of the clay was the prime reality for the early artist. Its curvature did not induce an attitude to pictorial space distinct from that aroused by the flat wall or panel, except in so far as it encouraged the primitive tendency to make use of disparate viewpoints for the individual objects that were represented. This leads on to the conclusion that this surprisingly constant pattern was undoubtedly reflected also in Greek monumental painting.

White concludes his discussion of Greek pottery painting with the above words -- but this "surprisingly constant pattern" is more of an assumption than a proven conclusion - just like his final speculation concerning the Greek monumental painting that can no longer be seen.

******************************************

ANTIQUE PERSPECTIVE THEORY AND POMPEIAN PRACTICE

White now goes on a mining expedition to unearth the three documents of ancient literature that may, or may not, relate to a theory of pictorial perspective.

Though actually, two of the writers, Euclid and Lucretius are only concerned with optics.

And Vitruvius only discusses the topic in reference to architectural renderings in a book about architecture.

The passage is so brief, an interpretation invites the kind of microscopic word-by-word study that religious scholars usually reserve for passages from sacred texts.

So... I'm going to skip this section, and its application to Alberti, to move on to White's discussion of Pompeii, beginning with the Second Period, 70-10 BCE, when pictorial illusions began to appear on the walls.

In the earliest phases of the Second style the painted architecture is so simple that problems of perspective scarcely exist. Perspective only makes its entry in the later stages, when new depths are created in the wall, and prospects open up beyond it. At the present time this early flowering of the monumental architecture of the Second style is only fully visible in the remaining decoration of three houses: the Villa of the Mysteries at Pompeii; that of Publius fanmus Sinistor at Boscoreale; and a town house in Pompeii, the House of the Labyrinth. Of these three, it is the last named which by virtue of the composition that is repeated on the side walls of the Corinthian oecus about which the house is balanced, is undoubtedly the most important in the present context.

The solidity, and the structural clarity of this sharply drawn and boldly lit design immediately strike the eye. The firm foundation of this first impression is laid bare with the discovery that in the upper parts of the remaining section of the composition over forty receding lines in many widely separated planes, both vertical and horizontal, vanish to a single point low in the centre of the altar. A further half a dozen miss it only by an inch or so. This constancy of the recession to a single point, with only occasional aberrations, mostly in the small, repetitive detail where the ease of execution readily becomes the chief consideration, is repeated in the fragments on the opposite wall. It therefore represents a definite intention.

Despite the quantity of vanishing lines receding accurately to a point, it is quite clear that the composition is not fully unified. Although certain of the orthogonals in the bases actually recede towards the vanishing point, and others run quite close, the bases as a whole are not controlled by it. This inconsistency does not call attention to itself, as it is not near the strongly lighted centres of interest. The contradictions in the decorative vases and in the central altar itself are far more obvious. The former show a genuine internal inconsistency in drawing, since the mouths alone are seen from a high viewpoint that conflicts with the slightly lower setting of the vanishing point. The altar, on the other hand, presents a rather different problem. Here there is no question of confusion or inaccuracy. There is instead a radical change of viewpoint which is quite unparalleled elsewhere in the fresco. The sudden adoption of a slightly high viewpoint and of a foreshortened frontal or very softly oblique setting, right in the middle of the composition, seems to stem from a desire to reveal the solidity of this central feature, which would only show its fiat, forward surface in an accurate construction. The altar nevertheless remains the single radical departure from a visual unity which is others wise maintained throughout the composition, and, for the most part, with that extreme accuracy of construction which is entailed in the adoption of a single vanishing point.

A nice visit to the House of the Labyrinth can be found here

We only guess what the owner of this villa was thinking when he or she commissioned these murals.

My guess is that they wanted the place to feel more palatial than what they could afford - so they painted, instead of built, architectural features.

A less ruined example of the use of a vanishing point is to be found in the Villa of the Mysteries, on the back wall of Alcove A in Cubiculum 16. In this case the whole area of the triple vaults, involving a large number of receding lines, is centred, with a few minor inconsistencies in execution, on a single, central point. Here, however, there can be no question whatsoever of the co-ordination of the bases in the scheme. Their recession does not even run approximately into the same area, and individual surfaces occasionally show an actual divergence. This complete dichotomy does not, however, diminish the importance of the fact that in the upper area of this wall a quite extensive architectural complex has been unified about a single point, and a number of other examples, some more elaborate, some less, are to be found in this and in other rooms in the Villa dei Misteri.

It does not appear to me that the lines from the forward and rearward constructions share the same vanishing point:

And then there's also the issue of the architecture depicted on the adjoining wall.

It is similar, but seems to be completely independent -- leading me to guess that the artisans had a stock pattern and just repeated it from wall to wall, without consideration of the whole.

Sort of like wallpaper.

(BTW - White says the same thing a few pages later:

"This 'wallpaper' approach to pictorial space may even, paradoxically enough, be accompanied by the boldest efforts to run certain of the un-foreshortend elements upon one wall into the pictorial space that next door to it by means of illusionist foreshortenings upon the latter")

This confinement of focused recession to the upper parts of the architecture is also visible in the decoration of the Villa of Publius Fannius Sinistor at Boscoreale. In the fresco from the West wall of the summer triclinium, which is now preserved in the museum at Naples, practically all the downwards running orthogonals which can still be seen appear to have centred on a single spot. These lines, which number almost twenty, are all those associated with the colonnades that run back into space about a central court resembling those seen in the decoration of the Corinthian oecus in the House of the Labyrinth and constructed with similar accuracy.

Finally, in the wall of the cubiculum which has been set up in the Metropolitan Museum at New York, the two sections which again resemble the designs in the House of the Labyrinth both reveal the adoption of a single vanishing point for the cornices of the receding colonnades on either wing, and also for some of the orthogonals lining the central gap in the principal broken architrave.

This summary of the available evidence shows that there can be absolutely no talk of the development of increasingly accurate vanishing point perspective in Pompeii. Beyond the three decorative schemes which have been singled out lies nothing more.

A second fact, which militates against the idea of a genuine development upon Pompeian soil, is that in each one of the houses that have been considered vanishing points are only used in individual, even isolated composi dons. No general trend in the organization of pictorial space is indicated, for there is no demarcation line between these frescoes and their neighbours even upon grounds of quality. In the cubiculum at Boscoreale the dividing lines between compositions that reveal a tendency to use a vanishing point, and others that do not, occur within the boundaries of a single wall. Similarly in the Villa of the Mysteries there is no deterioration in the quality of frescoes in which the convergence to a single point is not observed.

These considerations lead directly to the conclusion that the Pompeian frescoes which are being discussed reflect advances that were made elsewhere.

Why should the use of a single POV and vanishing point be considered an advance?

Combined with his interpretation of Vitruvious, White concludes that "all evidence points to the existence, in antiquity, of a theoretically founded system of vanishing point perspective".

But even if that were so, there's no reason to assume that it was ever used other than in the practice of an architect's profession.

White now opens a wider discussion of fresco painting in Pompeii by remarking that:

"The relationship between the onlooker and the pictorial world implied in such masterpieces of figure-painting as the "The Initiation to the Rites of Dionysus", in which the action leaps accross the intervening real space of the room, is established with meticulous care in many of the finest architectural compositions."

It's too bad White was not as willing to digress from his focus on rectangular solids here as he occasionally was in discussions of 15th C. painting.

The Pompeian sense of space feels like none other -- with it's linearly connected heavy volumes set into an impossibly shallow space.

It feels so menacing - while the characters feel so gentle.

The importance of the architectural friezes in this room ( tablinum of Marcus Lucretius Fronto) in relation to the spherical field of vision and the artist's moving eye has been recognized for some time

That upper section certainly is complex - as White puts it:

"The simulation of a single curve by means of two short chords"

...as well as a higher POV for the upper register (the floor rises upward) than for the lower register.

Which leads to his summation: "lateral diminuations, splaying wings, steepening recessions.. accompanied by a sophisticated attack upon the problems of visual appearance and pictorial space"

It all feels quite stage-like to me, as a place where nothing real is ever supposed to happen - everyone is just playing an assigned role - creating a space that is socially, as well as visually, claustrophobic.

The probability that several artists, each with their own spheres of activity, collaborated in this decorative scheme is not difficult to establish. The likelihood is greatly increased by the treatment of the pair of mythological scenes which form the centre-pieces of the two main walls. In both of these delicately coloured compositions the planar contraction of the space depicted is very marked, and at times gives rise to uncertain relationships between the rather stiff little figures that have been gathered with eclectic zeal from extremely varied sources. The furnishings of the interior in the scene of ‘Ares and Aphrodite’ nevertheless discloses another aspect of the very approach to visual reality which is indicated by the more delicate construction of the miniature scaenaefrons upon the wall above it. The large couch that fills the middle ground is actually oblique in setting, even though the down, slope of its receding surfaces is so gentle that they scarcely seem to leave the plane at all. The rectangular central block, on which Eros stands, reveals an almost equally soft oblique construction, with its long and short sides both inclined at the same gentle angle to the horizontal. This even recession is no longer used for the block-like seat upon the right, or for the drapery-covered chair upon the left. Instead, the oblique construction is used in such a way as to approach a foreshortened frontal rather than a complex frontal setting. The long forward face of the block upon the right is almost, but not quite, set in the plane, while the short inner face runs much more sharply into depth. This pattern is repeated in reverse upon the left side of the picture. Here are essentially the same design, and the same approach to visual reality that were later to be exploited by Maso and Ambrogio Lorenzetti, by Fouquet and by Paolo Uccello, and which, finally, was to gain a theoretical basis in Leonardo’s system of synthetic perspective.

Should this painting really be considered "an approach to visual reality" ?

And why doesn't White mention the POV anomaly between the two couch seats, to the left and right?

The seats are about the same height, but we are looking down at the one on the right, but up at the one on the left.

Making an uncomfortable social setting feel just a bit more uncomfortable.

Who is that lady on the right, and why is she so uptight?

Mars and Venus truly seem to have come from different planets.

And Cupid feels like such a truculent little brat.

This picture seems to have been in the back of the mind of whoever did the scenic designs for the HBO series, "Rome", that was set in about the same time period as this painting was done.

One of the best, and most typical of the surviving transitional, late Third-style scenes is that of Orestes and Pilades before Iphigeneia’ from the House of the Citharist. The character of the spatial design is set by the slight, yet firm upslope of the evenly receding faces of the temple steps that dominate the centre of the composition. All the minor solids: the altar standing at the top of the steps on the right-hand side; the seat-blocks in the right foreground; the low stele on the extreme left, or the small altar in the central foreground, with its more sharply jutting forms; all of them are fully coordinated with the dominant oblique construction of the temple steps. It is only in the internal structure of the foot of the foreground altar, with its slightly overaggressive solidity, that there is a certain confusion in the drawing. The more gentle outwards recession at each side of the composition is a feature which was already noticed in the ‘Ares and Aphrodite’. The concern for the pictorial surface, another major characteristic of the mythological paintings of the Third style, revealed in the careful closing of the wings by foreground figures, and in the use of steps to create a level platform which, at the same time, is made to carry the figure composition upwards over the whole pictorial surface, is equally typical of such works.

Just as in the architectural view from the Fronto house, the upper platform is seen from a higher POV than the lower - making for a rather, dizzy, unsettling effect.

In the late Thirdsty1e painting of ‘Thetis in the Workshop of Hephaestus’, formerly in the house IX.I.7, the composition from the House of M. Lucretius Fronto is essentially repeated, but without the same degree of spatial crowding and contraction. A similar screen of architecture closes in the background, and the visual focus of the scene, in the polished shield held slightly to the left of the geometric centre, is stressed by the simple, heavy column. The spacious foreground is measured out by the work’blocks and the piled-up armour, and by Thetis’ throne and footstool on the right. Yet the busy confusion of the ground plan is less real than apparent. The majority of the stone blocks on the left are quite strictly in alignment with each other. All the faces nearer to the centre of the composition once again recede more steeply both in the blocks themselves and in the footstool on the right. The alignment of the forms upon the left is only buried to the casual glance by the oblique direction of its axes, just as it is buried also in the crowded towns and villages of San Francesco at Assisi. Here is no confusion, but the curving composition which both organizes and expresses in artistic form the everyday experience of the turning head and roving eye.

Designs such as these prove that the popular assertion that the artists of antiquity never achieved the spatial co-ordination of isolated solid objects has no valid basis. It is refuted by surviving works of art, as well as by the literary remains.

O.K., they're achieved spatial coordination -- but still, most of these spaces feel awkward -- and that aesthetic feeling was probably as irrelevant as it is in a lot of popular art, like this hand-painted movie poster from Ghana:

As White immediately notes, it's fun to have a little window onto a lost world -- but let's face it, these are not great paintings, probably because the client did not demand it.

And the stakes were not as high as they would have been in the church buildings where Giotto painted.

It is occasionally possible, where there is a series of like compositions, to obtain an actual cross-section of the numerous graduations in the interest in structural and spatial clarity visible within the hierarchy of Pompeian art. The four copies of the scene of 'Admetus and Alcestis’ in the museum at Naples make up one such sequence. A small, table-like seat, which appears in every version, starts out as a firmly constructed piece of furniture with the principal receding lines of its extreme oblique construction all converging clearly. Step by step it is transformed into a clumsy concoction of warped planes and tilting, uncertain members receding from each other in disorganized divergence. The more important elements of the composition show an equal range. There could be no clearer warning of the danger of asserting the limitations of antique pictorial art on the evidence of paintings which must represent, in many cases, only the lower rungs of such a hierarchy of coherence.

Unfortunately, I could only locate 2 of the 4 scenes that White has mentioned, and he did not indicate which versions he thought were more clumsy than others.

There is no convergence to the sides of either of the table-like seats shown above,

and the one below appears a bit more wobbly than the one above it.

But is that a fault -- or an enhancement to the narrative being presented?

Perhaps that character should be perched upon a wobbly seat.

Both paintings would fail to qualify for the 19th C. French salon -- but might be welcomed into galleries in the 20th C. when idiosyncrasies were sought rather than avoided. The first one reminds me of Botero.

Since these are the oldest, surviving examples of room size pictorial space in the world, there seems to be the expectation that they would succeed, or fail, as naturalism.

But maybe we should think of them as surrealists.

The increased use of the oblique construction, already noticeable in Third-style painting, is continued and intensified by the Fourth-sty1e artists. The setting attains a marked predominance throughout the entire range of quality, and is almost invariably used in the finest work. There is a similar increase in the strength as well as in the popularity of the extreme oblique construction. Often, as in the famous composition of ‘Achilles and Briseis’, a single oblique structure forms a background for the figures.

That single oblique structure certainly enhances the drama of this event

Everywhere the Fourth’ style mythological picture is highly independent of the constructional rules which govern the increasingly luxuriant framing architecture. This duality of approach can only be compared with that reflected in the fresco cycles of Giotto and his immediate followers. In all the surviving frescoes there appears to be only a single instance of a bold attempt to apply the rule that governed the small world within the picture to the architectural framework of the decorative scheme as a whole.

This unique pictorial adventure occurs in the Fourth-style decoration of the main wall of the atrium of the House of the Ara Massima. The front door and entrance passage are not central in relation to this atrium, but are situated opposite the left-hand edge of the impluvium. The visitor’s first impression of the fresco spread before him on the opposite wall is therefore gained from a position which almost exactly corresponds to that of the shield which hangs between the columns of the painted porch to the left of the central landscape panel.

The first, and most obvious peculiarity of the construction is the strong curve of the painted moulding of the lower border. This curvature is very marked, even in the short undamaged section beneath the right-hand flight of steps. It must have been extremely striking when the golden paint was new, and when it stretched unbroken from one wall of the atrium to the other, Less obvious, but still no figment, is a similar curve in the lower border of the central landscape panel. Higher yet, a further steeply hanging curve is implied by the strong up and outwards slope of the lintels of the doors to left and right. If attention is transferred from the horizontals to the verticals, it is difficult to talk with certainty of the left-hand porch, and of the nearby border of the central landscape panel. The latter is now tilted very slightly to the left, and this might well be due to the subsidence of the wall. No similar explanation holds good for the righthand porch and doorway. These must still have leaned considerably to the left when every possible allowance has been made. It is equally impossible to ignore the violent splaying of the parapet upon the right of these same steps and doorway.

There seems to be no escape from the conclusion that the painter of this fresco made a bold, and strikingly successful attempt to curve the whole design away from an onlooker standing well to the left of the centre of his symmetrically balanced composition. Pausing at the entrance to the atrium, ‘the visitor sees all the horizontals curve increasingly towards the right, whilst all the uprights start to tilt in vertical foreshortenings as his eye sweeps out and up. In spite of certain obvious shortcomings the fresco represents the culmination of the tendencies already apparent in the optical splaying of the buildings in the stage-like friezes in the House of M. Lucretius Fronto.

Definitely one strange wall!

Since we are looking down at those steps, the POV for the upper register of scenes would be at least 12 feet off the floor of the atrium.

And making the scenes curve away to the right -- that's just so bizarre.

In a large room, as opposed to a page in a book, straight lines will appear to curve anyway.

I wonder if this was the home of a man who painted scenery for the theater - or, maybe someone who loved the theater and illusions. This was a space meant to impress visitors, but not especially to be lived in.

A video tour can be found here

The story that opens with the dying reflections of an antique ‘artificial’ perspective is continued in the Third- and Fourth-style painting with the increasing popularity of freer, empirical methods. These were based upon the shifting observation of reality through the artist’s roving gaze. The vanishing axis pattern dominates the architectural framework of the wall, reflecting, not a mathematical application of Euclidean natural perspective to the realms of art, but a practical empiricism. This is equally expressed in the treatment of the inset, mythological and landscape panels. These reveal an ever more frequent use of an increasingly accentuated oblique setting. In the finest work a new degree of spatial organization is achieved, and a great advance is made along the road that finally leads, after a lapse of nearly fifteen hundred years, to the creation of a theory of synthetic perspective. Beneath the apparent welter of conflicting forms there lies a clear prefiguration of the two great strands that weave the spatial pattern of renaissance art.

White never explicitly declares that naturalism is the highest goal of painting and that its greatest achievement coincides with the invention of what he calls "synthetic perspective"

But that seems to be point behind this "great advance made upon the road"

No comments:

Post a Comment