One of 19 essays in the catalog of "Abstract Art : Abstract Painting 1890-1985" ..for the 1986 exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

**********

Jan Toorop (1858-1928) , Organ Sounds, chalk and pencil on cardboard

Jan Toorop, Song of the Times, pencil and chalk on paper, 30 x 38", 1893

Apparently the organizer of this collection of essays thought that Symbolism had something to do with the emergence of abstract painting. And so we have this essay about the Dutch Symbolists - as well as the adjacent essay about some French Symbolists. Neither essay goes so far as to assert that the one emerged from the other - but still it’s regrettable that so much attention is given to artists who did not make abstract paintings.

Whether or not Kandinsky, Delaunay, and Mondrian ever thought of their geometric shapes as symbols, obviously they strongly felt them visually. Though, perhaps, that's not so obvious to the art historians of today.

I can’t stand Jan Toorup’s Symbolist pieces.

The first one is too blurry to feel anything but goofy.

The other is just horrible.

I appreciate the element of ornamental Javanese (he was born on Java)

But the stiff anorexic figures and claustrophobic, tangled design repel me.

Blotkamp discusses the " Song of the Times" at length,

but it’s too painful for me to view.

Obviously, I could never be an art historian.

It would be a mistake to get really serious about the essence of any so-called art movements.Toorup’s Symbolism may be unviewable, but "Isle of the Dead", sometimes said to exemplify Symbolism - is one of my favorite paintings.

Toorup, an otherwise good painter, apparently decided to prioritize idea over visuality in his Symbolist work. That led to visual disaster - and it’s happened regularly throughout art history - from Old Kingdom Egypt until today.

Jan Toorop, Lady in White, 1886, 39 x 28

Here’s one of his earlier works that delights me.

The weird sense of space under the chair,

the tastiness of the white cloths.

It’s much like the work of his contemporary, Anders Zorn,

but quirkier.

Piet Mondrian, 1908, Devotion, 37 x 24"

Mondrian spent the summer of 1908 in Toorop’s little art colony,

but obviously the 34 year old artist was following his own inclinations.

This essay will mostly be about Mondrian, but before we go there, there are a few other artists under discussion.

Johan Thorn Prikker and and R.P.C. De Basel don’t interest me.

But Jacoba Van Heemskerck(1876-1923) —- Yikes!

Jacoba Van Heemskerck, Composition 1914, 29 x 42"

Jacoba Van Heemskerck , Composition 1922, 24 x 37

One website says she influenced the early work of Georg Muche.

(the Zehn Leuchtperpendikel shown in my post about German abstraction)

She’s practically a footnote in this essay - which essentially covers Mondrian’s early years as a painter - but she had such a range of style and feeling - all of it powerful. A large selection of her work is now online at the Kunstmuseum The Hague.

Relevant to the theme of this book, she practiced Anthroposophy.

Watercolor, 29 x 19, 1917-18

The primal forces of creation.

Composition 107, 1920

As complex as any hour in my day.

Fun on the water.

Composition 13, 1916, 5 x 6 "

resembles the stained glass of a medieval cathedral - except that there is no recognizable narrative.

Could easily become a Jonah and the Whale.

Some of her designs actually were put into glass:

Stained glass window, 1920 , 42" high

Landscape 2, 1913-14

a night scene laden with the mystery of a beckoning path

1906

Jacoba Van Heemskerck was even good at that precise kind of portraiture for which Northern Europeans, like Jan Van Eyck, have been noted since the fifteenth century.

Jan Van Deen (1886-1977) Painting 2, 1913, 23 x 35"

This kind of work was not accepted by critics and the artist opened a gallery selling the work of others. Today its understated mystery might have been better received.

Jacob Bendien (1890-1933) Composition 1913, 58 x 137"

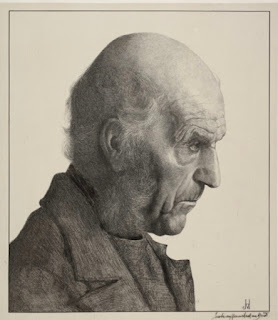

Jacob Bendien. Self portrait, 1910

Like this youthful self portrait much more than anything else I’ve found.

Jacob Bendien, Self portrait, 1930

Janus de Winter (1852-1951), Aura of the Egotist, 1916, 22 x 30"

Janus de Winter, Musical Fantasy on Wagner, 1916, 26 x 33"

Janus devWinter , Imagination of a Feeling of Willpower, 1916

Both the paintings and the titles are intriguing - though I can’t see much connection between them.

He did this work in his sixties and though he lived to 99, little of his later work can be found online.

Mondrian's adherence to Theosophy was also an important issue in his relationship to van Doesburg, painter, theoretician, and propagandist of De Stijl. In terms of spiritualism van Doesburg's early diaries and literary work are often rather exalted and contain numerous esoteric notions. 58 It is not certain whether he was ever a member of the Theosophical Soci-ety, but he definitely sympathized with Theosophy. In 1914-15 he replaced his naturalistic way of painting with an expressive, semiabstract style, influenced by Wassily Kandinsky and in particular by the Dutch painter de Winter (examples shown above) Van Doesburg was very impressed with the latter's work and per-sonality. His own work of that period (examples below) shows aural images and "spiritual por-traits" similar to de Winter's. Drawings

Theo Van Doesburg, Cosmic Sun, 1915, 9 x 12", pastel on paper

Theo Van Doesburg, 1915, 12 x 9, pastel on paper

Here’s a few of his cosmic pieces, they’re simple and small - but quite appropriate for a book about art and spirituality.

He’s more like a visionary than a seeker.

Van Doesburg

Van Doesburg

I really like the drama between these truncated triangles.

I’m guessing the golden section has been applied more than once.

Noel Martin, 2006, 28 x 22

By way of comparison, here’s a much later piece from an American graphic designer.

Similar in their extreme precision in size, temperature, placement, and tone,

yet quite different in effect.

Much less drama in the Martin piece

but it’s also much more enjoyable.

It’s both relaxed and lively,

Perfect for the office of an optometrist.

Stanley Dean Edwards, 2024

While here’s a contemporary piece that’s more hectic than dramatic.

Nothing profound here - unless you appreciate the importance of chaos.

Way too intense for my gentle temperament.

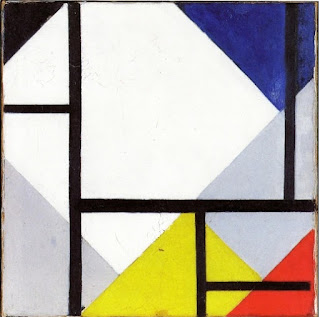

Van Doesburg, Composition Decentralized, 1924, 11 x 11"

Wow! Kinda like Mondrian - but you know it isn’t.

Feels heavier - with less sense of playful mischief.

Unstable, it wants to rotate clockwise.

Van Doesburg, Counter Compoition XIII, 1925, 19 x 19"

Van Doesburg

These are some really delightful geoforms - simple and quite different from those of his friend, Mondrian - even when he uses similar elements.

His pieces are more assertive and less subtle.

The author has documented how all of the artists mentioned were involved in some kind of metaphysical practice - though he also tells us:

The extent to which these artist expressed their Theosophical convictions in their artwork, is difficult to determine.

***** Mondrian*****

Composition with Colored Planes, 1917, 18 x 23"

A weird, puzzling, understated dynamic where the center of the design is an empty space.

I wonder how it looked when first painted. I don’t trust the reproductions.

Mondrian, Evening on the Gein, 25 x 33", 1906-7

Earlier in his career he had painted, mainly peaceful landscapes (the above is given as an example) and a few vaguely symbolic figurative Works, which generally suggest an artist of contemplative nature

Mondrian, Spring, 1908, 27 x 18"

In 1908 Mondrian’s style changed radically, and became more outspoken in content.

(The above as well as "Devotion" were given as examples)

Certainly reminds me of Munch’s "The Scream" of 1893..

Church at Domberg, 1910-11, 44 x 29

Before knowing the title, I assumed this was a university building or even a warehouse as designed by a retro-architect like H.H. Richardson - with some kind of important meeting taking place behind those really tall windows on the third floor. More like an illustration than a painting for me.

With few exceptions Mondrian stayed away from the use of fanciful occult images of the kind that can be found in Besant's and Leadbeater's work, images in which aural appearances play a large role. Mondrian's point of view is reminiscent of Thorn Prikker's fifteen years earlier, when he rejected the affected symbolism of his fellow Symbolists. Mondrian's opinion was that one could obtain higher knowledge within visual reality, a view that Rudolf Steiner had advocated during his lectures in the Netherlands in 1908. The booklet in which these lectures were published was treasured by Mondrian for the rest of his life.

Even Mondrian's ordinary themes could hold a deeper meaning for the already initiated.

For example, one is able to perceive in Mondrian's series of high-rising towers on a flat ground (example given above)both a traditional Christian reference to God and a non-Christian symbol of the combination of the male and female principles.

Neither of those references occurred to me.

But they certainly do in the piece shown below:

Constable, Salisbury Cathedral, 1825

Sea After Sunset, 1909, 16 x 29"

His series of coastal scenes could be interpreted as the unity between water, earth, fire, and air, or in their poorest state, with only water represented as an image symbolizing the beginning of things.

A piece that I interpret the same way.

The wonderful miracle of planet earth.

Evolution, 1910-11, each panel about 70 x 33

A foray into figurative religious-like art that I would call brave but goofy.

He may have felt the same way since he did not continue in this direction.

It reminds me of Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze of 1902.

An important change occurred in Mondrian's art at the end of 1909 and beginning of 1910.

The loose brushwork is replaced by a more controlled design, in which colors are evenly applied in clearly defined fields. Without a recognizably strict system, the paintings show a strong preference for symmetry and geometric division of the surface along its horizontal and vertical axes, further defined by a grid of oblique lines. These characteristics are most strikingly present in the monumental triptych Evolution, 1910-11

Mondrian's clearest confession of his theosophical conviction and as such quite exceptional in his entire oeuvre because of its unnatural character and overt symbolism.

The triptych represents the theosophical doctrine of evolution, man's progression from a low and materialistic stage toward spirituality and higher insight. One can easily follow the process from the left panel, then to the right panel, and finally to the center panel. Virtually everything plays a part in Mondrian's symbolization of evolution: the position of the figure's head, the eyes, the shape of the nipples and navel, the flowers - all details supported by subtle changes of color.

Large Nude, 1911, 55 x 38

I would call this another failure - it’s dull as both a figurative and non-figurative painting.

Mondrian was very receptive to the influence of Cubism, when in 1911 he encountered the first real examples at an exhibition of the Moderne Kunstkring (modern art circle) in Amsterdam, which he assisted in organizing. ……Mondrian developed his work into a radical Cubism within a short period of time, while maintaining his theosophical concepts of art and life.

Steenhoff recognized this when he described Mondrian's new paintings at an exhibition in Amsterdam in October 1912: "I perceive a favorable development now, in spite of very daring abstractions, in terms of spiritual self-containment and introspection. The work is less pretentious; the painter has found himself in a purer sense; even if it seems to me that he groans naively under the constraints of the preconceived notion that art should totally negate matter. "

I agree with Steenhoff . (BTW, he was a big fan of Van Gogh, and highly critical of Cubism)

Oval Composition, 1914, 44 x 33"

Why were viewers left to guess at its obvious name: "The Egg of Life" ?

Mondrian also deviated from orthodox Cubism by making line and color, his visual means, absolute (example shown above). In his evolutionary thinking line and color, reduced to essential contrasts between horizontal and vertical and between the three primary colors, were supposed to express the unity that was the final destination of all beings, the unity that would resolve harmoniously all antitheses between male and female, static and dynamic, spirit and matter. This all-encompassing visual system, of the utmost importance for the future evolution of his work, is already rudimentarily indicated in a few sketchbooks with annotations. Thus the foundations for Mondrian's Neoplasticism were laid in Paris from 1912 to 1914. Back in the Netherlands during World War 1, he further developed his concept in a critical, but stimulating dialogue with the artists with whom he started the magazine De Stijl in 1917, particularly Theo van Doesburg and Bart van der Leck.

This is what I would call a successful piece of religious art - and yes, it does deviate, in a good way, from Cubism.

Composition, 1919, 33 x 41

Perhaps a Go master would appreciate something subtle.

Is it really any more compelling that the Ellsworth Kelly pieces that were arranged by chance:

Ellsworth Kelly, Spectrum Colors arranged by chance, 1951

Not as tedious as the example shown below - but almost.

Agnes Martin, untitled V, 1981

For an infinity of variations, AI could certainly do the job.

*********

Here’s some more early Mondrian that appealed to me:

Mondrian, Nude, 1908, 33 x 16"

Very good at figure drawing

Mondrian, self portrait, 1918

Very good at portraits, too.

Mondrian, Irrigation Ditch with Cows, 1901

Smells cold, damp, and lonely - as well as like cows.

Mondrian, Sea after Sunset, 1909

A love song to our planet.

A piece I would like to own.

********

We can’t deny that Mondrian identified with Theosophy as Heemskirck did with Anthroposophy.

The author of this essay notes that a only a few Dutch abstract painters did not.

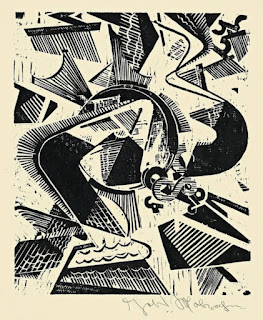

Erich Wichman ( 1890 - 1929), Small landscape 1912

No dimensions were given - I’m guessing that it’s the size of a postcard.

Apparently this artist struggled to make a living , and his pieces still sell for little.

Wichman, lithograph, 1918

This essay has examined only a narrow aspect of early Dutch abstract art, a major part of which was esoterically oriented, particularly toward Theosophy. There were only a few exceptions, the sharp-minded Erich Wichman, for example, a painter of extremely interesting abstract works, who never had anything to do with the high ideas of most of his colleagues and made fun of them.

Note: the author, Carel Blotkamp, is an artist as well as critic and historian.. I think I’ll follow him on Instagram