Quoted text is in YELLOW. Text quoted from other authors is in GREEN *************************************************************************** ****************************************************************************

Oskar Kokoschka, 1907

This chapter is about Oskar Kokoschka who:

abandoned Klimt as a model. Jugendstil art (Art Nouveau) did not go deeply beneath the skin, Kokoschka argued: it “set out only to beautify the surface and made no appeal to the inner life.” He criticized Klimt’s paintings for their presentation of the erotic drive through symbols and ornaments, saying that the artist depicted society ladies trifling with sexuality. Moreover, he considered Klimt’s paintings of women to be unemotional.

Koskoshka doesn't seem to have enjoyed romantic affairs with society ladies as much as Klimt did. He must have taken the games of love too seriously.

He also had less interest in cultivating a sense of beauty.

Kokoschka brought a combination of psychoanalytic insight and expressionist style to bear on his portraits, which he painted with the belief that truth in art is based on seeing the inner reality. He described himself as a “psychological tin can opener”: When I paint a portrait, I am not concerned with the externals of a person—the signs of his clerical or secular eminence or his social origins. . . . What used to shock people with my portraits was that I tried to intuit from the face and from its play of expressions, and from gestures, the truth about a particular person"

1913

In drawing the emerging sexuality of his young models, Kokoschka captured both their natural openness and their shyness. For example, in his 1907 drawing "Standing Nude with hand on Chin", the model's awkward pose suggests her discomfort at posing nude. Here, as well as in "Female Nude Sitting on the Floor with hands behind her Head", we can see Kokoschka's fascination with how movement betrays a psychological trait or social awkwardness. Moreover, the boyish figure and angular outlines of the female body in these two drawing emphasize the sitter's youth. The girl in both drawings is most likely Lilith Lang, a fourteen year old fellow student at the School of Applied Arts.

1909

These early drawings, especially the "Reclining Female Nude", illustrate how Kokoschka revealed, through angular bodily contours, both the free, unconstrained gestures and the unconscious emotional urges of his young female models.

Here's a Degas reclining nude for comparison -- and though it's more angular than what his contemporary voluptuaries of the academy would produce, it still feels soft and fleshy compared to Kokoschka.

Picasso, 1902

Does the angularity of this Picasso also express the

"unconscious emotion of its young female model" ?

"unconscious emotion of its young female model" ?

Or is it's calligraphic strength more about the emotion of the artist ?

I don't know how to tell the difference -- but then, I also don't sense that the "Standing Nude with hand on Chin" is uncomfortable with posing nude, or that the "Female Nude Sitting on the Floor with hands behind her Head" betrays a psychological trait or social awkwardness.

Kandel does not tell us what that psychological trait might be.

I also don't feel any more "emerging sexuality" in these drawings than I do from any other nude drawings of young people.

If you're looking for sexuality in a nude, you can't help but find it -- and Kandel was looking for Kokoschka's response to the 1905 publication of Freud's "Three Essays in Sexuality" in which "Freud describes the physical maturity of adolescence as merely catching up with the rich sexuality of infancy"

But on the other hand -- you can't deny the youthful sexuality in Kokoschka's book, "Die Träumenden Knaben" (The Dreaming Boys), written and illustrated in 1907-8 when the artist was 21.

Here's a sample of the text:

you gentle ladies

what springs and stirs in your red cloaks

in your bodies the expectation of swallowed members

since yesterday and always?

do you feel the excited

warmth of the trembling

mild air —I am the werewolf

circling round

when the evening bell dies away

I steal into your garden

into your pastures

I break into your peaceful corral

my unbridled body

my body exalted with pigment and blood

crawls into your arbors

swarms into your hamlets

crawls into your souls

festers in your bodies

The book was dedicated to Klimt - who is depicted above giving physical support to the fainting young artist.

This is an amazing book of brilliant designs - the lithographs being first exhibited in 1908 at the Kunstschau Wien organized by Klimt where he declared "Kokoschka is the outstanding talent among the younger generation."

Has the muddled idealism and awkward urges of adolescent male sexuality ever been given such a beautiful tribute? I get the feeling that, unlike Picasso, he was not a teenage whoremonger.

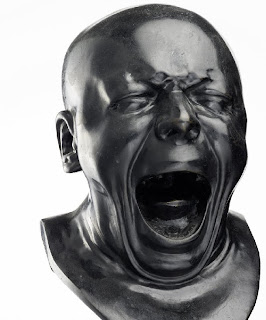

Self portrait as a Warrior, 1909

As Kandel tells it, following Claude Cernuschi, Kokoshka's painted clay self portrait of 1909 marked his break from the decorative qualities of Klimt.

In this bust, Kokoschka attempts to make his art both more truthful and more jarring by exposing the techniques he used to sculpt it: he exposes the physical methods he used to work the unfired clay surface, the technique he used to peel back the skin and to suggest the blood flowing just under the surface. Moreover, to emphasize his own individuality as an artist, he pressed his hands into the clay and used unnatural colors—the red above the upper eyelids and the blue and yellow on the face and hair—to convey extremes of emotion beyond all social or painterly decorum. Here we see Kokoschka’s first attempt to forsake the realistic use of color and texture in favor of their emotional qualities. By freeing color from its representational function, as Van Gogh had started to do, Kokoschka shifted his art’s emphasis from pictorial accuracy to pure expression.

Artists have never restricted their use of color to its representational function or placed their primary emphasis on pictorial accuracy -- at least the artists whose works have ended up in art museums.

And what expression could be more pure than an infant's scream? But who wants to listen to it for any kind of aesthetic pleasure or intellectual comprehension ?

Does this piece have any value outside its context in European cultural history? -- a question that would never occur to me regarding Kokoschka's graphic work. Except for some facial details, it has the sculptural design qualities of a turd.

As Kandel relates, that historical context involves several leading Viennese intellectuals including Karl Kraus, the publisher and satirist, and Adolph Loos, the Modernist architect who would make the arrangements for the many portrait commissions Kokoschka did in 1909.

portrait of Karl Kraus, 1910

portrait of Adolph Loos, 1909

Titian, Pieta, 1575

At this point, Kandel launches into a discussion of European Mannerism, as a prelude to Kokoshka's new approach to painting.

Kokoschka notes in his autobiography that he was inspired by Titian’s use of light and color to create the illusion of movement and thereby to supplement color with perspective. He also writes about Titian’s Pieta, in which the artist uses light to transform and re-create space, with the result that the beholder’s eye is no longer directed by the signposts of contour and local color but can focus on the intensity of light: “As a result, my eyes were opened as they had been in childhood when the secret of light first dawned on me.”

Light also defines the forms in Titian's "Flora" (1517), painted 60 (!) years earlier --- but the surfaces of those forms are more closed and less turbulent.

You might call his later painting less sensual and more spiritual.

But since the overall design of the "Pieta" feels weaker to me - I'm wondering whether this looser treatment of form was the consequence of diminished mental power, rather than a preferred innovation.

Kandel puts the dramatic facial sculptures of Franz Messerschmit (1736-1783) into the tradition of Expressionism - though, as you can see, his forms are quite closed and tightly rendered.

Thus, a chain of influence extends from the Mannerism of Titian and El Greco to the early Expressionism of Messerschmidt and Van Gogh, to the Expressionism of Kokoschka. A decade later. Gombrich and Ernst Kris, both scholars in the Vienna School of Art History, drew attention to this lineage from Mannerism to Expressionism and saw Expressionism as a synthesis of the classical mannerist tradition in art, aspects of primitive art, and caricature. Arguably, this synthesis was first achieved in European portraiture by Messerschmidt’s character heads and Kokoschka’s Self-Portrait as Warrior and the portraits of 1909 to 1910.

Edvard Munch, "The Scream" 1893

Kandel then relays the tradition that the German art dealer, Paul Cassirer, coined the term "Expressionism" to distinguish Edvard Munch from the Impressionists.

No date is attached to this usage, but "The Scream" does predate "Warrior" by 16 years.

Munch’s art emphasized the timeless, subjective expression of deeply rooted, universal emotions in a stressful, anxiety-ridden modern world, whereas the Impressionists focused on the fleeting outward appearance of persons and things in natural light. In its most general sense, Expressionism is characterized by the use of exaggerated imagery and unnatural, symbolic colors to heighten the viewer’s subjective feeling when looking at art.

In "its most general sense" Expressionism can also be found in the paintings of Manet, Monet, Degas, and Renoir.

Kokoschka used the short brushstroke developed by Van Gogh and the powerful expression of emotion developed by Munch, but he carried those extensions of mannerist technique further, introducing an artistic exaggeration of the face, hands, and body that had previously been restricted to caricature. Whereas Van Gogh used exaggeration primarily to enhance external characteristics and Munch used it primarily to convey external displays of terror, Kokoschka used exaggeration to reveal a new internal reality—the psychic conflicts of the sitter and the tortured self-inquiry of the artist.

This seems to be a spot-on comparison -- though I don't think there's anything new about depictions of tortured self-inquiry or having psychic conflicts. What about the self portraits of Rembrandt ?

Other than for his training and elite social contacts, Kokoschka might be called an "outsider artist".

Portrait of Martha Hirsch, 1909

Regarding the early portraits, Kandel quotes Hilton Kramer as follows:

There is a depth of empathy and a determination to remain undeceived by the masks of public demeanor that together have the effect of seeming to penetrate to the inner core of the psyche itself

Which is quite similar to what Georg Simmel had to say about the portraits of Rembrandt , though Simmel spoke of "inner life" instead of "psyche"

Kandel quotes Gombrich as follows:

What upset the public about Expressionist art was, perhaps, not so much the fact that nature had been distorted as that the result led away from beauty. That the caricaturist may show up the ugliness of man was granted—it was his job. But that men who claimed to be serious artists should forget that, if they must change the appearance of things, they should idealize them rather than make them ugly was strongly resented.

Portrait of Lotte Franzos, 1909

Did the public think that Kokoschka had made an ugly painting -- or just that he made his subject aappear unattractive ? (and I'm always skeptical when anyone ventures to speak about public opinion without some kind of data)

Concerning the above example, apparently young Mrs. Franzos was not pleased with her portrait, but the artist wrote:

“I painted her like a candle flame: yellow and transparent light blue inside, and all about, outside, an aura of vivid dark blue….She was all gentleness, loving kindness, understanding.”

I find these women and the paintings of them to be attractive - though not as breathtaking as that early Titian shown above.

Again quoting Hilton Kramer:

Kokoschka places each of his subjects in a pictorial space that is neither the space of nature nor that of some recognizable domestic Interior. It is an infernal space, at once eerie and unearthly, haunted by demons and threatened by dementia. The light in this space, with its bizarre chiaroscuro and frightening tints, is fugitive and unabashedly intimate.

Hans and Erica Tietze, 1909

I don't feel that any of the people depicted in these three 1909 portraits are "haunted by demons and threatened by dementia"

They just seem like real people in the gaze of a sensitive, romantic young man -- rather than as they might be presented in a formal social setting

The Trance Player (portrait of Ernst Reinhold), 1909

KOKOSCHKA’S FIRST PORTRAIT was of his friend Ernst Reinhold (whose real name was Reinhold Hirsch ). His objective in painting Reinhold, and in subsequent portraits, was “to recreate in my own pictorial language the distillation of a living being.”

To depict Reinhold’s unconscious striving, Kokoschka uses bold, loud, unnatural colors and applies the paint rapidly, working it into the canvas unevenly and rubbing it vigorously with his fingers and the handle of the brush. In parts of the portrait, he scrapes the paint on the canvas with a stick or his hand. Kokoschka places the redheaded actor dramatically in the center of the foreground and has him engage the viewer directly with his piercing blue eyes. The artist employs an abstract background here, as in his other portraits, not just in reaction to Klimt’s ornamental background, but also as a way of focusing dramatically on the subject, particularly the subject’s inner life. The art historian Rosa Berland writes that this background, plus the painting's rough texture and ghostly lighting, calls attention to the process of painting and thus functions as a visual metaphor for “the process of artistic creation.”

The artist is quoted as saying that he had overlooked the fact that he had given his friend four fingers instead of five - and Kandel tells us that this symbolizes a sense of incompleteness in the man's personality.

But he did give Ernst a fifth knuckle --- allowing for the fifth finger to be bent inwards, out of sight.

(In the version to the left, above, I've removed that knuckle, so you could see what four fingers would actually look like)

Actually -- until Kandel mentioned it -- I never missed that fifth finger at all --- and still don't.

The design might have even been stronger if he had left out that knuckle as well.

Rudolf Blumner, 1910

In the two years between 1909 and 1911, he painted over fifty portraits, mostly of men. In them, he reveals character dramatically, especially through the sitter’s eyes, face, and hands. Sometimes, as in the 1910 portrait of Rudolf Blumner, he uses those parts of the body to convey deep anxiety—or sheer terror. Kokoschka respected Blümner as a friend of modern art and wrote of him that he was “a tireless fighter in the cause of modern art. . . a sort of modern Don Quixote, hopelessly engaged in battle against the entrenched prejudice of his times, and this was reflected in my portrait of him."

Most of the early portraits are half-length, usually stopping just below the hands. Kokoschka believed that hands could convey emotion, and he emphasized these “talking hands” in his portraits. Sometimes, as in the Blümner portrait, the hands are outlined or stained in red. Blümner’s right hand is raised as if to make an important argument with his hand as well as his body; the energy of his movement is conveyed upward into his body by the ruffled right sleeve of his jacket. The red color suffuses Blümner’s face, providing ominous spots of high color in an otherwise deftly executed pale complexion. His facial features are delineated in red, suggesting veins or arteries. The viewer’s attention is drawn to BlUmner’s eyes, one of which is larger than the other. He does not look directly at the viewer but gazes distractedly elsewhere, as if obsessed with his inner self.

The paint in this portrait is thin and dry, with a rubbed or scraped quality, indicating that Kokoschka was willing to compromise observation of detail in order to capture his own excited state.

It's always problematic to think about paintings seen on a computer screen, Unfortunately, Kandel has given this, his most thorough examination of a single painting, to a work which can only be found in thumbnail size on the internet (unless you purchase a high-res image)

I can only say that Dr. Blumner does seem to be a nervous, confused kind of fellow who would find comfort in a nervous, confused kind of painting.

And in that category of nervous, confused kinds of painting -- one might ask why this one is worth collecting and remembering, other than for its historical value. That kind of question does not appear to interest Kandel.

Auguste Forel, 1910

But Kandel is interested in whether these portraits "see into the sitter's psyche" -- and there's a fascinating story connected to the one shown above.

The subject, an internationally known psychiatrist, rejected the portrait, claiming that it made him appear to be the victim of a stroke that affected his right hand and eye - an effect which the artist himself conceded.

But unfortunately for Dr. Forel, that's exactly what happened to him two years later. Had the artist recorded a transiet ischemic episode?

If so -- that would be good reason to place this piece into the Ripleys-Believe-it-or-Not Museum -- but not especially an art museum.

I admit that, once again, this effect never occurred to me until I read the text. Indeed, both of Forel's eyes seem far more focused then Blumner's.

But since the portrait does make him appear more like a crazy old street beggar than a distinguished scientist, I can understand why the subject might have rejected it.

Ludwig Janikowski, 1909

Janikowski, a literary scholar ,and friend of Kraus, is depicted as descending into psychosis, which he did shortly after the portrait was completed. Kokoschka portrays this mental state by focusing on Janikowski’s head and painting it as if it were in motion, slipping out of the bottom of the picture. The bright, almost surrealistic patches of color on his face and in the background create a sense of terror, which people characteristically feel as they begin to have a psychotic breakdown. Janikowski looks directly at the viewer. We comprehend his enormous anxiety and feel sympathetic toward him because he looks so terrified — his eyes are asymmetrical and frightened, his ears are asymmetrical, he lacks a neck, and his coat jacket merges with the background. To further suggest that Janikowski is at the edge of madness, Kokoschka uses the wooden end of the praintbrush to care lines and create deep furrows and wrinkles on his face, eyes, mouth, and bright red ears, as well as on the background

But his eyes seem so gentle -- he feels like a prophet or artist.

BTW - by this account Janikowski was already a patient at Steinhof Sanitorium when Kokoschka painted him.

And now that we finally get a larger image, the aesthetic value of these paintings is more apparent.

Finally, we get to the self portraits, beginning with this Halloween mask for the cover of an avant garde periodical.

Fu Shan, d. 1684

Those heavy facial markings remind me of the more eccentric Chinese calligraphers, like Fu Shan.

In the famous self-portrait poster designed in 1911 for the art magazine Der Sturm (The Storm), Kokoschka responds to the brutal assessment of the Viennese critics who branded him “chief savage” for his expressionist art and dramas. He presents himself as an outcast, a cross between a criminal (shaved head, powerful jutting jaw) and Christ, grimacing and pointing with his hand to a bleeding stigma in his right chest, as if to reprimand the Viennese for the wound they had inflicted on him.

A hundred years later, Koskoschka would have been designing album covers for Death Metal bands.

He really excels at graphic design.

1918-9

In one self portrait his eyes are open and questioning, and his large hands form the center of the picture. He is anxious, almost terrified, an impression heightened by streaks of dark green in the background converging upoon him.

1917

In the self-portrait of 1917, Kokoschka points to his left chest with his right hand. His face and eyes express a sadness reflecting not only the injury to his ego entailed by the loss of Alma Mahler three years earlier, from which he still had not fully recovered, but also a physical injury sustained in the war, a stab wound that pierced his left lung. The pain of this double loss is also reflected, as Berland points out, in the agitated application of the paint and in the contrasting and threatening blue sky of the background, heralding a storm.

Rather than a presentation of a wounded psyche -- this seems more like a straight-on presentation of self -- in the first person rather than second or third.

He feels very alive, and in-this-moment.

1913

Kandel does not discuss this one - but here's a pre-war self portrait as a painter - and he doesn't look disturbed at all, does he ? He just looks serious

Van Gogh, Self Portrait with Bandaged Ear and Pipe, 1889

Van Gogh’s vehement brushstrokes and his use of arbitrary, audacious colors were adopted and modified by Kokoschka. However, when Van Gogh was experiencing emotional turmoil, he was much more subtle and subdued in his attempts to convey that turmoil to the beholder. The most revealing example of this difference is Van Gogh’s extraordinary self-portrait of 1889.

Just before Christmas 1888, after a serious quarrel with his friend Gauguin, Van Gogh, who suffered from manic-depressive illness, sliced off part of his left ear with a razor. He then painted a portrait of himself with a bandage over his left ear. This self-portrait is considered to present the artist at the lowest point in his life, yet Van Gogh looks out at the beholder calmly.

I don't sense "calmness" here at all -- this looks like a wild animal who has just been put into a cage.

This also seems to be a third-person observation of that one poor devil who Van Gogh knows the best.

And though it may be just hindsight -- this does seem to be an adult life at the end of its trajectory rather than near the beginning. The puzzlement and wonder of Kokoschka's self portraits seem exuberantly boyish by comparison.

Photo of an Hysterical woman, Jean-Martin Charcot

Kandel's focus now turns to Kokoschka' expressive depiction of hands that "may well have been influenced" by the photos printed in the books written by Charcot (1805-1893), a pioneering neurologist.

Niccolo Dell-Arca, 1462

Donatello, 1460-65

Though there are some examples of women with expressive hands in the air from an earlier period.

El Greco, 1577

Jean-Baptiste Wicar, 1790

Looking for more examples, I walked through the old master galleries at the Art Institute of Chicago

Carlo Crivelli, 1487

I was a bit surprised that I could only find a few. Usually, even if the theme was dramatic, like the crucifixion shown above, the gestures were more restrained. It would appear that art was mostly expected to provide comfort, not intense drama.

But of course, you can always find exceptions.

Ttree remarkable and distinctly different examples show how Kokoschka used hands to communicate an emotional state between two people.. The first is the 1909 portrait of the baby Fred Goldman, entitled "Child in the Hands of its Parents." The mother’s right hand and the father's left hand seem to protect and shelter their child. The hands stand in for the parents, and they are engaged in a dialogue of shared affection.. There is both an interesting contrast and a sense of dynami collaboration between the two hands. The father’s is outstretched, both protective and restrictive, with vigorous red hues. The mother’s is pale, inich softer, more relaxed and gentle. This use of hands turns a portrait of a child into a family portrait

Even in this wonderful and loving painting, Kokoschka reveals his uncanny ability to discover vulnerabilities not always obvious to others. He paints a broken finger on the father's hand, an early childhood injury that the sitter himself had forgotten.

Hans and Erica Tietze, 1909

A very different, perhaps even more powerful dialogue of hands is played out in the double portrait of Hans Tietze and Erica TietzeCuiirat . Both art historians, they often published together and sat at the same desk every day for years. At the time the double portrait was painted, in 1909, Hans was twenty-nine and Erica was twenty-six, and they had been married for four years. The double portrait i was, according to Kokoschka, meant to symbolize their married life.

Hans, a student of Riegl and a member of the Vienna School of Art Hitsory, later taught Gombrich and championed contemporary art. Erica, a specialist in Baroque art, posed separately for the painting.

Although they are husband and wife, Kokoschka paints them as if were unrelated. He uses the occasion to focus on the contrast between the sexes and illustrated that contrast with distinctive sexualized gestures and bodily positions. Their hands, which in Hans’s case are disproportionally large, create a bridge between them, but the two people do not face each other. With their eyes looking in different directions, they seem to be caught in a revealing, sexually charged conversation with their hands, a conversation that also involves tle viewer. They emerge as two independent people, each with an inner direction and sexual needs. Carl Schorske comments on the light behind Hans conveying a sense of male sexual energy. Recapitulating the role of Alma Maliler in The Wind's Fiancee, Erica seems to withdrawing from her husband, who leans slightly forward as if to approach her.

But they aren't looking at each other -- and they don't seem to be enjoying themselves.

In their discussion, Hans seems almost desperate to make his point, while Erica doesn't really seem to care as she looks forward with a blank stare.

How can such an interaction be called "sexually charged"?

FinaIly Kokoschka uses hands to reflect the instinctual strivings of children. His interest in the inner life of young children first appeared in the remarkable portrait Children Playing, painted in 1909. This portrait depicts five-year-old Lotte and eight-year-old Walter, the children of bookstore owner Richard Stein. Kokoschka does not depict the two children in idealized poses that suggest childhood innocence, as earlier artists would have done. Instead, he suggests through their body language, irregular coloring, and the vaguely defined background on wliich they are lying that the relationship is neither neutral nor innocent

.

Ihe children are portrayed as struggling with their attraction to each other and with the conflict that this attraction sets up within each of them and between the two of them. The boy appears in profile, looking intently at the girl, while she is lying on her stomach, raising herself on her elbows and facing the viewer. As in the painting of the Tietzes, Kokoschka uses the children’s arms to communicate a link between the two of them. The brother’s left hand is reaching for his sister’s right hand which is clenched iii a fist.

Is she about to sock him because he is touching her arm ?

Her face might be saying "I've had enough of this pest"

Kandel suggests that it was seen by contemporaries as being erotic - which would explain why the Nazis condemned it as 'degenerate"

But I agree with what Gombrich had to say about this painting:

In the past, a child in a painting had to look pretty and contented. Grown-ups did not want to know about the sorrows and agonies of childhood, and they resented it if this subject was brought home to them. But Kokoschka would not fall in with these demands of convention. We feel that he has looked at these children with a deep sympathy and compassion. He has caught their wistfulness and dreaminess, the awkwardness of their movements and the disharmonies of their growing bodies. . . . His work is all the more true to life for what it lacks in conventional accuracy.

Renoir, 1895

Above is a happier vision of children - which also seems exceptional in comparison with so many earlier portraits that depict children as uncomfortable miniature adults.

KOKOSCHKA BURST UPON the Viennese art scene like a werewolf in the garden, he captured on the surface of a canvas the unconscious instincts lying deep within the human psyche—his own as well as his sitters’. Like Freud, lie grasped the importance of Eros in children and adolescents, as well as in adults.Like Klimt and Sclinitzler, he embraced early on the intimate interplay between erotic and aggressive instincts that characterizes the Viennese modernist painters.

This feels like a boiler plate conclusion that's been tacked on at the end of a discussion that doesn't really justify it.

The only overtly erotic pieces that Kandel has shown us after the "Dreaming Boys" lithographs were his self portraits with his lover, Alma Mahler

Self Portrait with lover (Alma Mahler), 1913

Oskar was not the man to meet Alma's gaze

Oskar was not the man to meet Alma's gaze

In their several double portraits, Alma is typically calm while Kokoschka looks at once passive and agitated, as if he is about to suffer a mental collapse. In the most powerful of these, "Windsbraut", Kokoschka and Alma lie in a boat, shipwrecked in mid-ocean, buffeted by the waves of their tempestuous relationship. She is sleeping calmly and he, as usual, is agitated, rigidly hovering near her. In this painting, Kokoschka uses thick paint and dark colors and builds the surface of the painting layer by layer, giving it depth and conveying a sense of the emotional turmoil he was experiencing. The redder and more emotionally charged colors blend into his deadened skin tone, while the green, earthy colors enliven Alma.

The Wind's Bride, 1914

Passion spent, Alma lies content - but Oskar is thinking about the future. Hers will not be including him, but couldn't he have figured that out on day one ?

1921

Kandel does not include the above painting done after the break up -- it depicts the artist with the life size Alma Mahler sex doll that he had once commissioned. Ouch!

Is Kokoschka,here, really revealing "the unconscious instincts lying deep within the human psyche" - as if it were a new, psychological discovery ?

Don't most people eventually learn how it feels to get dumped? At least he has given us a pretty good picture of it -- from the inside.

”All that is required of us is to release control. Some part of ourselves will bring us into unison. The inquiring spirit rises from state to state, until it encompasses the whole of Nature. All laws are left behind. One’s soul is a reverberation of the universe. Then too, as I believe, one’s perception reaches out towards the Word, towards awareness of the vision.”

The above is an excerpt from Kokoshka's 1912 manifesto entitled "On the Nature of Visions"

Kandel does not quote it.

It would seem to affirm Raymond Barglow's assertion that the avant garde artists of turn-of-the-century Vienna were pursuing a path away from science rather than in consort with it.